Neutrino 'flip' wins physics Nobel Prize

- Published

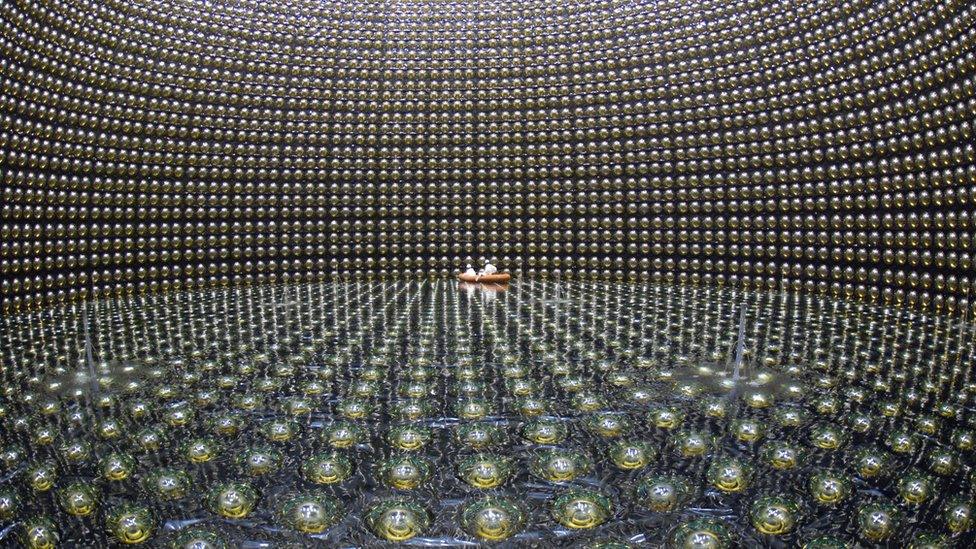

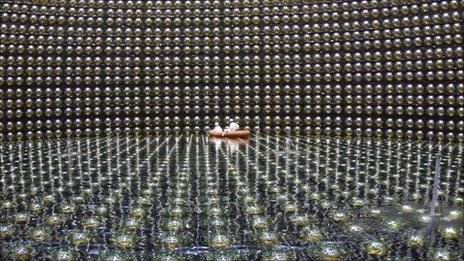

Crucial measurements were made at the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector in Japan

The discovery that neutrinos switch between different "flavours" has won the 2015 Nobel Prize in physics.

Neutrinos are ubiquitous subatomic particles with almost no mass and which rarely interact with anything else, making them very difficult to study.

Takaaki Kajita and Arthur McDonald led two teams which made key observations of the particles inside big underground instruments in Japan and Canada.

They were named on Tuesday morning at a news conference in Stockholm, Sweden.

Goran Hansson, secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which decides on the award, declared: "This year's prize is about changes of identity among some of the most abundant inhabitants of the Universe."

Telephoning Prof McDonald from the conference, he said: "Good morning again - I'm the guy who woke you up about 45 minutes ago."

Prof Kajita and Prof McDonald will share prize money of eight million Swedish kronor (£0.6m)

Prof McDonald was in Canada, where he is a professor of particle physics at Queen's University in Kingston. He said hearing the news was "a very daunting experience".

"Fortunately, I have many colleagues as well, who share this prize with me," he added. "[It's] a tremendous amount of work that they have done to accomplish this measurement.

"We have been able to add to the world's knowledge at a very fundamental level."

Prof Kajita, from the University of Tokyo, described the win, external as "kind of unbelievable". He said he thought his work was important because it had contradicted previous assumptions.

"I think the significance is - clearly there is physics that is beyond the Standard Model."

The mysterious neutrino

Second most abundant particle in the Universe, after photons of light

Means 'small neutral one' in Italian; was first proposed by Wolfgang Pauli in 1930

Uncharged, and created in nuclear reactions and some radioactive decay chains

Shown to have a tiny mass, but hardly interacts with other particles of matter

Comes in three flavours, or types, referred to as muon, tau and electron

These flavours are able to oscillate - flip from one type to another - during flight

In the late 1990s, physicists were faced with a mystery: all their Earth-based detectors were picking out far fewer neutrinos than theoretical models predicted - based on how many should be produced by distant nuclear reactions, from our own Sun to far-flung supernovas.

Those detectors mostly entail huge volumes of fluid, buried deep underground to avoid interference. When such a vast space is littered with light detectors, neutrinos can be glimpsed because of the tiny flashes of light that occur when they - very occasionally - bump into an atom.

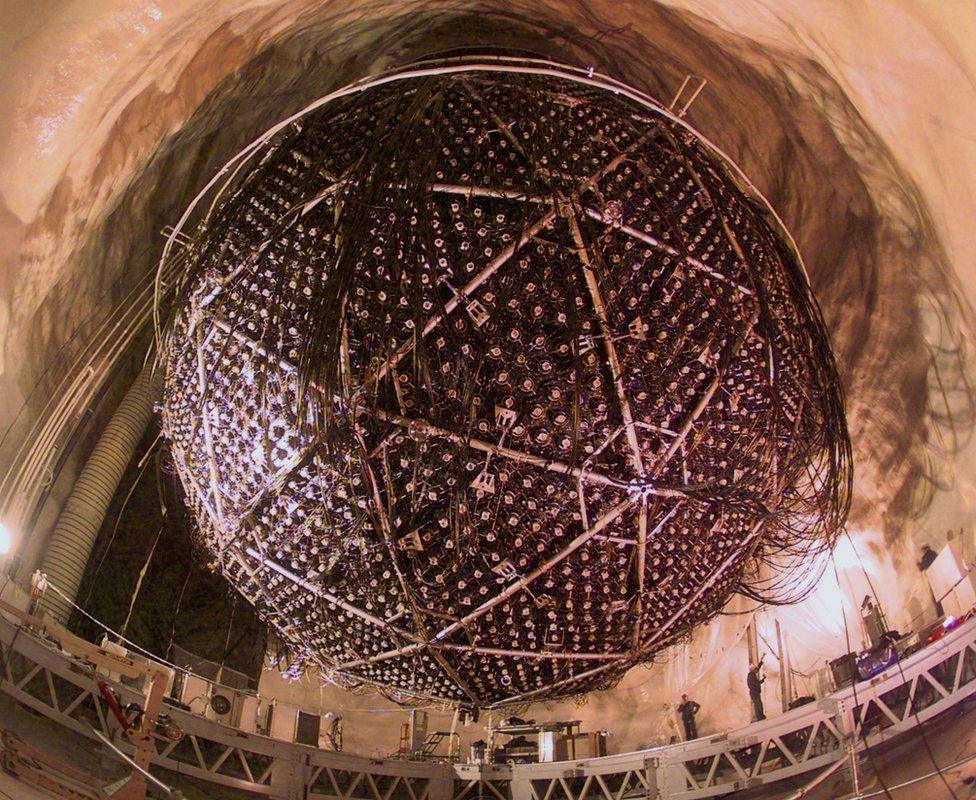

They include the Super-Kamiokande detector beneath Japan's Mount Kamioka, where Prof Kajita still works, and the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Ontario, Canada, run by Prof McDonald. Both are housed in mines.

Shape shifters

In 1998, Prof Kajita's team reported that neutrinos they had caught, bouncing out of collisions in the Earth's atmosphere, had switched identity: they were a different "flavour" from what those collisions must have released.

Then in 2001, the group led by Prof McDonald announced that the neutrinos they were detecting in Ontario, which started out in the Sun, had also "flipped" from their expected identity.

This discovery of the particle's wobbly flavours had crucial implications. It explained why neutrino detections had not matched the predicted quantities - and it meant that the baffling particles must have a mass.

This contradicted the Standard Model of particle physics and changed calculations about the nature of the Universe, including its eternal expansion.

The Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, like Super-K, is housed in a cavern inside a mine

Prof Olga Botner, a member of the prize committee from Uppsala University, said although the work was done by huge teams of physicists, the prize went to two of the field's pioneers.

She said Prof McDonald had proposed and overseen the building of the Sudbury observatory in the 1980s, and been its director since 1990. "He has been the organisational and intellectual leader of this venture."

Prof Kajita, meanwhile, did his PhD research at Kamiokande and then led the atmospheric neutrino group, "trying to make sense of the data they were getting" in the late 1990s.

Cracked model

Prof Stefan Soldner-Rembold, a particle physicist at the University of Manchester, said the prize recognised "a ground-breaking discovery by two large experimental collaborations" led by the two laureates.

"The discovery of neutrino masses and of neutrino oscillations are the first cracks in the Standard Model of particle physics," he told the BBC, adding that with other large-scale experiments currently being planned, "the era of exciting discoveries in neutrino physics has only just begun".

The total number of Nobel physics laureates recognised since 1901 is now 201, including only two women.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences also decides on the chemistry Nobel - announced tomorrow.

The first of the 2015 Nobel Prizes, for physiology or medicine, was awarded on Monday by the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet. It was shared by researchers who developed pioneering drugs against parasitic diseases.

Previous winners of the Nobel Prize in physics

2014 - Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura won the physics Nobel for developing the first blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

2013 - Francois Englert and Peter Higgs shared the spoils for formulating the theory of the Higgs boson particle.

2012 - Serge Haroche and David J Wineland were awarded the prize for their work with light and matter.

2011 - The discovery that the expansion of the Universe was accelerating earned Saul Perlmutter, Brian P Schmidt and Adam Riess the physics prize.

2010 - Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov were awarded the prize for their discovery of the "wonder material" graphene.

2009 - Charles Kuen Kao won the physics Nobel for helping to develop fibre optic cables, external.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published6 October 2015

- Published7 August 2015

- Published7 October 2014

- Published14 February 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published15 June 2011