Curiosity rover: The reward for 'whale watching' on Mars

- Published

Whale Rock is about 50cm high and is made from sediment grains that bounced along a rippling stream bed

Whale Rock. It's got quite a story to tell.

When scientists first saw it in images returned from Nasa's Curiosity rover on Mars, external, they really weren't sure what to make of it.

Sitting proud on top of a stack of finely layered mudstones, this coarser sandstone outcrop seemed a little out of place.

So, the team commanded the robot to drive up and down for a bit, to look at some other enticing geology in Gale Crater.

But each time Curiosity came back for another peek, the head-scratching continued.

What was Whale Rock, and why was it there?

This week the team released its considered interpretation of the sediments observed in Gale during more than a year's roving by Curiosity.

The report, published in Science magazine, external, describes how these sediments are likely the remains of streams and rivers that flowed over the crater's rim and across its floor, slowing and branching into deltas that ultimately fed a succession of persistent lakes.

And Whale Rock, it turns out, has something of a starring role in this story.

"It's the rock that gives us confidence that we've got our model right," says Sanjeev Gupta, a senior scientist on the mission.

Much of what is in the Science paper was first discussed last December in a mission-team teleconference with reporters.

The intervening months have witnessed the hard graft needed to corral all the evidence into the kind of arguments that will pass muster in a peer-reviewed scholarly journal. And those arguments are compelling.

The dipping rock strata in Gale align with the direction of water flow - towards the mountain

The coarser gravels that the robot saw out on the crater floor, near its landing point, gave way to progressively smaller-grained rocks as it drove south, closer to Gale's dominating central mountain, Aeolus Mons (Mount Sharp). And these dipping strata ended in a thick collection of finely layered mudstones.

The laminations are what you would expect when plume after plume of sediment pulses into a lake, loses energy and settles out of the standing water to build up the bed.

And Whale? It sits above 10m or so of these exquisite mudstones, somewhat nestled in them, and lens-shaped.

Whale has laminations, too, but its larger grains are those of a sandstone, meaning its deposition environment was more energetic. Its sediments were carried in rippling water.

All that head-scratching has concluded that Whale marks the physical edge of a lake - the interface with the delta that was feeding it.

There are two ways it could have formed.

Sanjeev Gupta: "Our analysis follows many months of detailed debate and argument"

One interpretation is quite straightforward: it is the delta deposits actually encroaching into the lake, filling little gullies.

The second possibility is a bit more involved: it could be where the lake has receded at some point, and the feeding stream from the delta has cut down and eroded a new channel. The stream's own sediments have then rolled into this channel but have later been encased by the finer muds when the lake level has come back up.

Either way, you are looking at a rock recording of events that occurred, perhaps over just a few hours and days, more than three billion years ago on another planet.

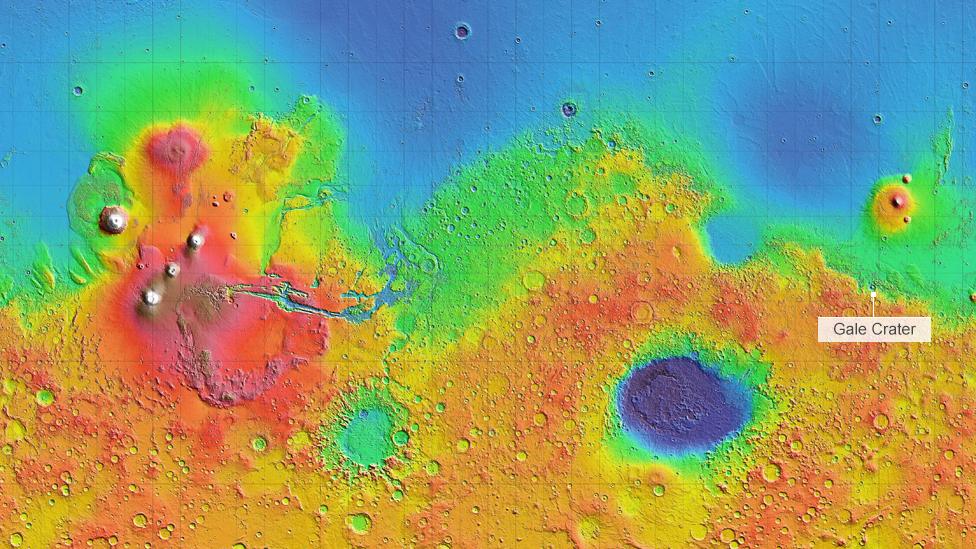

Gale Crater sits on the "dichotomy" - the divide between the northern lowlands and the southern highlands

"So, one explanation for Whale is a static model, and the other is a dynamic time model," explains Prof Gupta, from Imperial College London.

"The latter may be right, and that would be really exciting because it is telling us something about the water budget changing. But the important thing is that we are seeing the interface between the rivers and the lakes.

"Whale is a marker for us that they existed at the same time, and that really gives us confidence in particular that we are seeing ancient lake deposits."

Curiosity's big drive to Mount Sharp saw it climb up through 75m of sediments.

What we know of deposition rates in water environments on Earth suggests this stratigraphy took anywhere from 10,000 right up to 10 million years to accumulate.

And if even higher sediments at Mount Sharp (these have not been directly investigated by Curiosity but look the same from satellite imagery) are taken into account, this deposition time becomes even longer.

Higher still: Curiosity is still only in the lower reaches of Mount Sharp

And here is the "whale of a problem" (excuse the pun) that Mars scientists now find themselves grappling.

All the climate models of early Mars have failed to simulate conditions in which liquid water could run and pool on the surface long enough to produce the stratigraphy seen in Gale. The air was too rarefied; it was simply too cold.

But the mudstones and sandstones seen by Curiosity disagree. On their evidence, it is not even as if the ancient lakes were ephemeral. The rover sees no examples of the types of sediments that are associated with dried-out lakebeds, or even the kinds of glacial deposits that might suggest the water was frozen for long periods.

One tantalising consequence of all this is the possibility that the planet may once have featured a large body of water somewhere on its surface. This could have produced the atmospheric humidity, the rains and snows, needed to drive the features seen in Gale.

For decades, researchers have wondered if the flat, northern lowlands could have held an ocean during Mars' early history. The latest Curiosity results are re-igniting interest in this idea, says John Grotzinger, the lead author on this week's paper and the former project scientist on Curiosity.

"The simplest explanation is that there probably was a body of water out there that was creating an environment at the dichotomy (the boundary between Mars' northern lowlands and southern highlands), and at Gale Crater it supplied water moisture to the northern rim that flowed into the crater basin," the Caltech professor speculated.

"Either all of these geological observations, which seem to be adding up in the same direction, are incorrect (and we always have to be open to that possibility); or we're simply missing something. Perhaps, we don't have the greenhouse gas inventory and climate conditions for early Mars correct yet.

"I don't know what we're missing but I think we're headed for a long-lived controversy in the absence of complete information."

Utah humpback: Whale Rock takes its name from a much larger sandstone feature in Canyonlands National Park