Curiosity Mars rover 'solves mountain riddle'

- Published

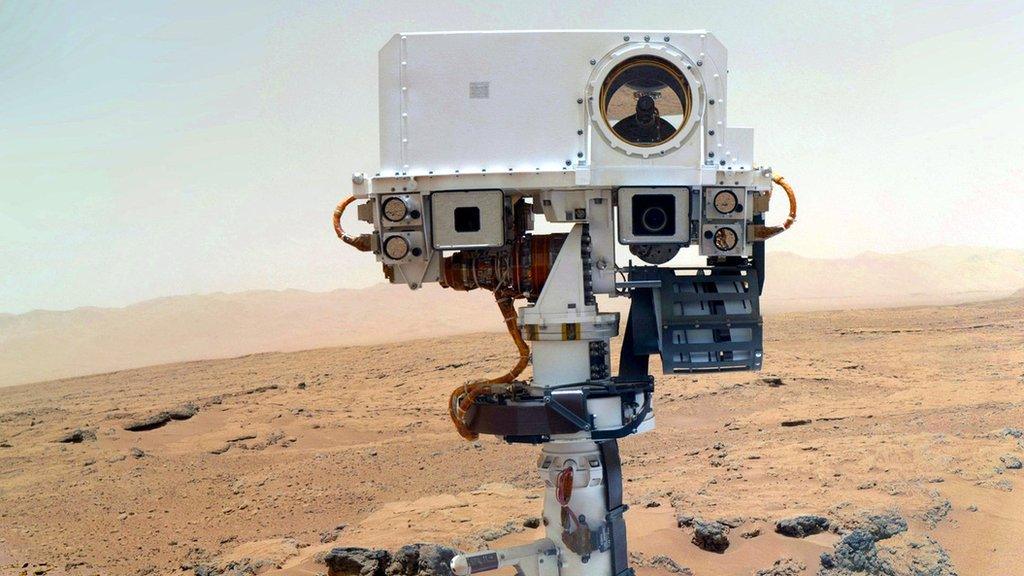

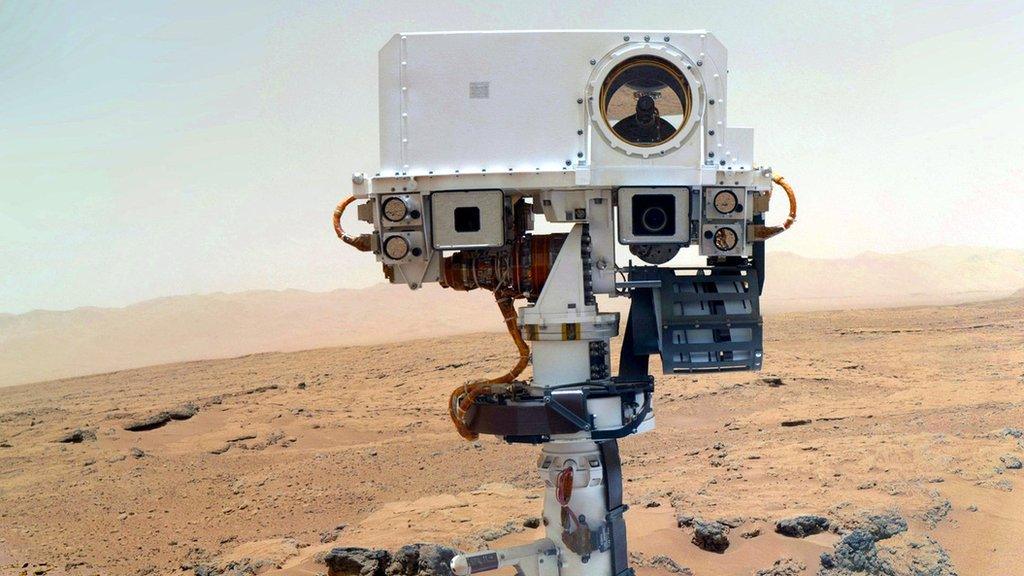

The Curiosity rover took over a year to drive to the foothills of Mount Sharp

Scientists working on Nasa's Curiosity rover think they can now explain why there is a huge mountain at the robot's landing site in Mars's Gale Crater.

They believe it is the remains of sediments laid down in successive lakes that filled the deep bowl, probably over tens of millions of years.

Only later did winds dig out an encircling plain to expose the 5km-high peak we see today.

If true, this has major implications for past climates on the Red Planet.

It implies the world had to have been far warmer and wetter in its first two billion years than many people had previously recognised.

Ancient Mars, says the Curiosity team, must have enjoyed a vigorous global hydrological cycle, involving rains or snows, to maintain such humid conditions.

One tantalising consequence of this is the possibility that the planet may even have featured an ocean somewhere on its surface.

"If we have a long-standing lake for millions of years, the atmospheric humidity practically requires a standing body of water like an ocean to keep Gale from evaporating," said Dr Ashwin Vasavada, the Curiosity deputy project scientist.

For decades, researchers have speculated that the northern lowlands could have held a large sea in Mars' early history. The latest Curiosity results are sure to re-ignite interest in that idea.

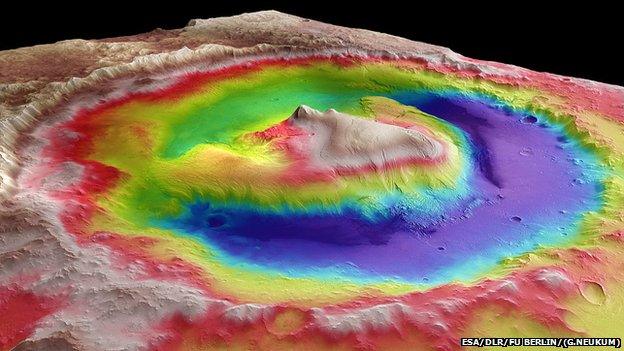

An elevation model of Gale crater: The central peak was not formed in the impact event

Craters like Gale often feature central mounds that are created as the ground rebounds after a bowl-forming impact from an asteroid or comet.

But Mount Sharp is far too big to be explained in this way.

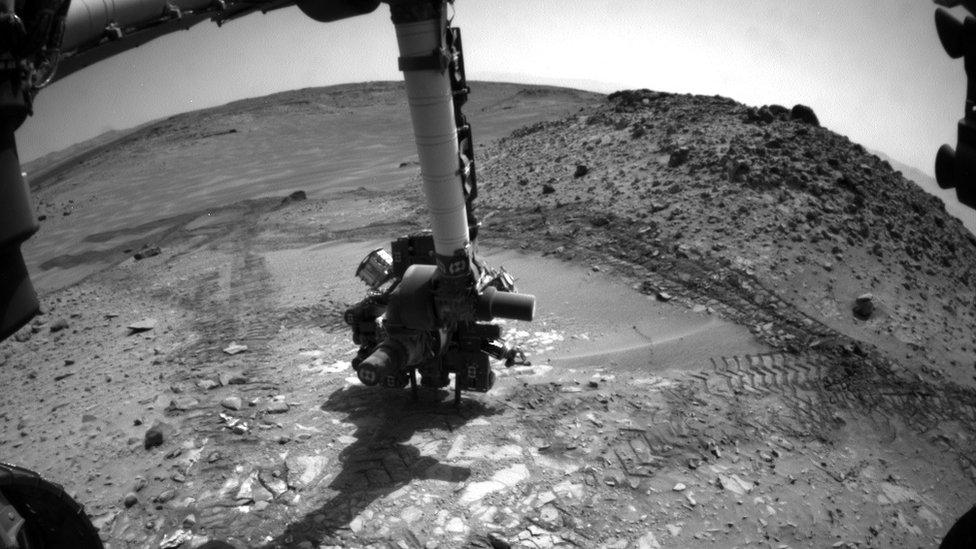

Curiosity's revelation follows from over a year's geological observations as it drove south towards the big peak from its 2012 landing site, out on the crater's plain.

In that time, the robot saw abundant banded sediments that were very obviously deposited by ancient rivers.

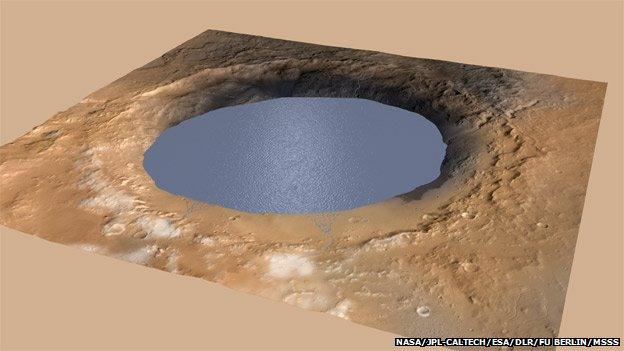

And the further south Curiosity rolled, the clearer it became that this fluvial activity ended in deltas and static lakes at the bowl's centre.

But the critical tell-tale was the inclination of these sediment beds, which the rover could see all dipped down towards the mountain, even as it climbed to higher and higher ground.

"We always see this same systematic pattern, which is quite intriguing," observed mission scientist Prof Sanjeev Gupta from Imperial College London, UK.

What this suggests is that water was running downhill from the crater rim towards Gale's centre where it would have pooled.

Over millions of years, the sediment raining out of this static body of water would have built the layers of rock - stack upon stack - that now make up Mount Sharp.

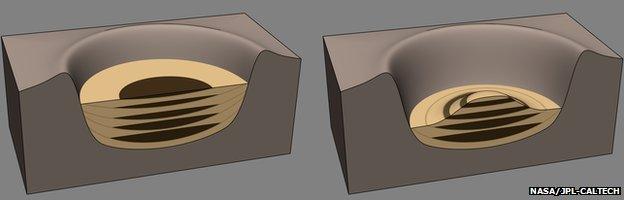

The peak stands proud today, says the team, because subsequent wind erosion has had many hundreds of millions of years to remove material between the crater perimeter and what is now the edge of the mountain.

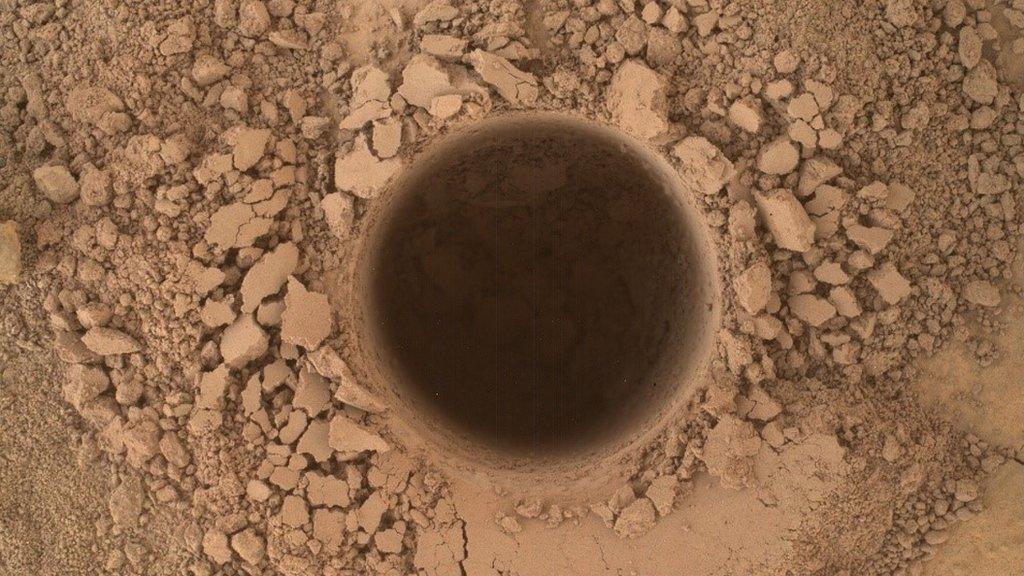

Sediment would have "rained out" of the still lake water to build Mount Sharp's rock layers

Curiosity has witnessed some spectacular layered rocks - the consequence of past water activity

Curiosity project scientist Prof John Grotzinger saluted the rover's careful field work.

The mystery of Mount Sharp, he argued, could only have been solved by a robot on the ground - not by satellite observations.

"There is no way to have recognised this from orbit," he told reporters.

"All that driving we did really paid off for science. It didn't just get us to Mount Sharp - it gave us the context to appreciate Mount Sharp."

There are still many outstanding questions.

The research team needs to understand better how persistent the water might have been through time; the activity that built the mountain could have been quite episodic.

And the notion that Mars was a lot warmer in the past is at odds with current climate models for that time.

"Even with a thicker atmosphere of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases like water, sulphur dioxide or hydrogen, it's difficult in models to raise global temperatures enough. But unless you do so, any liquid water would quickly freeze," explained Dr Vasavada.

The team hopes to answer some of these questions in the coming months and years as Curiosity climbs the mountain and studies its different rock layers.

The diagram shows how the crater may have filled with lake deposits (brown) through time (L), before wind then sculpted the central mountain we see today (R)

The layering was seen systematically to dip towards Mount Sharp in the centre of the crater

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published25 September 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published1 August 2014

- Published6 May 2014

- Published27 March 2014

- Published9 December 2013

- Published9 December 2013