Four views: How can we save the rhino from poachers?

- Published

An endangered northern white rhino

Rhinos are in trouble. The ancient Sumatran rhino has been declared extinct in Malaysia, external, following the fate of black rhinos in West Africa in 2011.

Central Africa's northern white rhino has been reduced to four animals, and conservationists say the more plentiful southern white rhinos are under unprecedented attack from poachers eager to sell the horns to Asian and Arab buyers.

How can we save the rhino? Four experts discuss the problem with the BBC World Service Inquiry programme.

Danene van der Westhuyzen: Licence hunters to kill ageing rhinos

Danene van der Westhuyzen is one of only a few qualified female professional hunters in Namibia, and the first female dangerous game professional hunter ever to qualify in Namibia. Namibia has the largest concentration of black rhino on earth - nine currently live on Ms van der Westhuyzen's land under her protection.

"We're on the ground a lot: we try and be out in the veld every day, walk the tracks and try to spot the rhino. It's not that easy because it's a huge area, but we try. And the people know that, so they better not try their luck.

"When a big black rhino male gets past its productive stage it will get pushed out by the younger males, and as soon as that happens this big rhino, because it's bigger, starts killing off all the other black rhino.

"I would phone up the government and I would say: 'I've got this problem rhino, this one big bull has killed two rhino already on our property, we have to make a plan.' But it's so expensive to move a rhino.

Namibia's older black rhino population needs to be carefully managed

"So the Ministry of Environment and Tourism decided to start auctioning off these post-productive bulls. They said we need to give out some licences and see if we can generate money to help conserve these rhinos. With each black rhino that is sold, the government gets $250,000 to $500,000 (£163,000 to £326,000).

Danene was at an auction at the Dallas Safari Club in the US where Texan millionaire Corey Knowlton paid $350,000 (£228,000) for a licence to track and shoot a Namibian rhino.

"I had tears in my eyes afterwards because we hoped for so much more. Everybody thought it would go for $1m (£650,000), but unfortunately there was such negative publicity around this. Corey had to have protection for him and his family for years afterwards, which is totally ludicrous.

"I don't think a trophy hunter is going to shoot a rhino to try and stop the poaching. What a trophy hunter does is pay for an animal and that money goes into conservation.

"I think the demand will continue whatever."

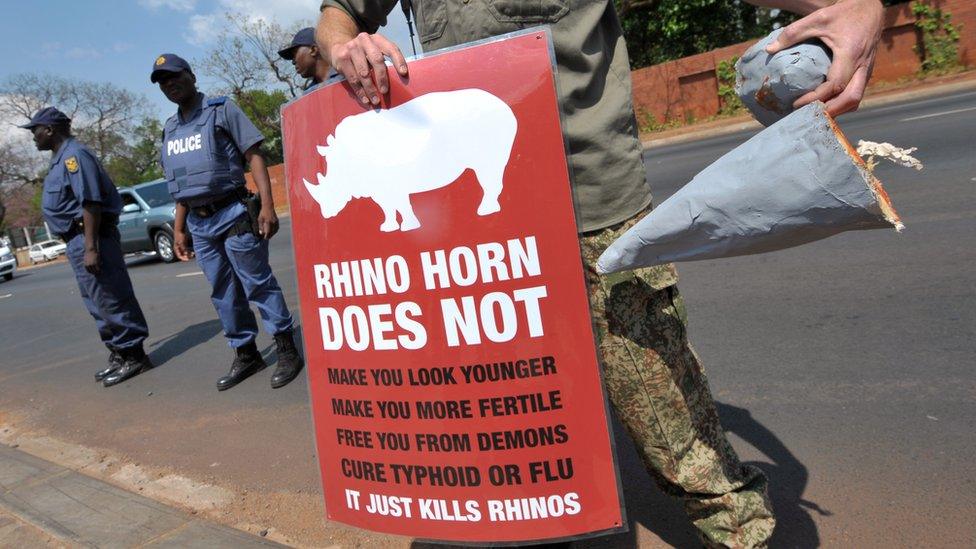

Huang Hong: Tackle the demand for horn products

Huang Hong runs an NGO called Change in Vietnam, which is one of the largest markets for rhino horn.

"It's quite desperate right now. There are three types of people using this.

"One is people who have cancer or arthritis or some serious sickness because it is so commonly believed that rhino horn is a magic medicine that can cure every disease.

"Then there are business people and high-ranking officials who have money. Rhino horn can be a symbol of their status or power, and they can also receive it as a bribe. And rich men use it as medicine like Viagra. It's just so ridiculous, because it doesn't work.

Ground up rhino horn is seen by many in Vietnam as a miracle cure-all

"We are working in hospitals, organising workshops with western doctors and traditional medicine doctors. They then talk directly to the patients and say 'it doesn't work, so stop killing the innocent animals.'

"The people that use this probably don't care that much if the rhino dies or not. Our culture and history involve fighting the wildlife rather than protecting it.

"I think changing awareness will take time."

Damian Vergnaud: Cut the horns to save the rhino

Damian Vergnaud runs the Inverdoon Game Reserve in South Africa. The reserve's first baby rhino in 20 years was born there last week.

"We've been attacked by poachers a few times. They fly above us at night with choppers; we were under attack once for a week, they came every night, trying to kill our rhino. It was very difficult.

"We came up with this horn treatment, where we inject dyes to denature and destroy the value. We make 50 holes and it ends up like Swiss cheese."

But in some cases rhino with dyed horns have still been poached, so Damian devised a more radical scheme involving 3D printing:

"The concept is quite simple. We take a picture of the rhino, using a 3D computer design programme, and create a horn mould with the 3D printer. We cut the rhino's real horn off and fill the mould with liquid plastic and aluminium. It dries very quickly and when we remove the mould, we have a horn which is the same colour, shape and size as the original.

Damian Vergnaud has pioneered the use of 3D printed fake horns

"In small game reserves like mine where there are five or six rhino, it's very easy to communicate [to poachers that the horns are not real]. But I don't say it's the solution for everywhere.

"In a big park like Kruger Park where they've got thousands of rhino, the killing would not stop immediately. The rhino will still die for a period. But quite soon the criminals would see that they are taking enormous risks of getting shot for nothing, to pick up some plastic."

Duan Biggs: Legalise the horn trade

Duan Biggs is a Research Fellow at the University of Queensland but grew up in South Africa's Kruger Park.

"It's very clear to anyone engaging in rhino conservation that the status quo is a dismal failure.

"The game rangers who used to do important work monitoring the habitat [have] no more time for that, they're out fighting poachers.

"If you were to have a legal market for rhino horn, the animals would effectively be conserved. This is a resource that we can harvest humanely and sustainably from a live animal.

"You dart the rhino and you remove its horn and transport it to a vault that's centrally managed and tightly secured. You have stringent monitoring systems for who is buying the horn.

"If you set up a legalised market well, you could actually fund enforcement to a much larger degree than it's being funded now.

"Our estimate is that the demand for horn, based on the illegal supply, could be met by the 5,000 white rhino which are on private land in South Africa. In addition, we have quite large stockpiles of horn.

"Think of rhino being poached and their horns hacked off, and being left lying for a day or two while they bleed to death, versus a well-managed operation with a qualified vet where you can remove the horn and then it grows back, and the rhino is still alive and you can get numerous horns from that rhino during its lifetime.

"It's a misconception that we're arguing that if you legalise trade there will be no poaching. There will always be poaching.

"We're arguing that with a legalised trade that is well-managed, you are far more likely to have rhino conserved than under the current situation."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published22 September 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published9 September 2015

- Published21 April 2015

- Published9 February 2014