Team wants to sell lab grown meat in five years

- Published

Professor Mark Post of Maastricht University explains how he and his colleagues made the world's first lab-grown burger

The Dutch team who have grown the world's first burger in a lab say they hope to have a product on sale in five years.

Researchers are to set up a company to look at making the burger tastier and cheaper.

The team had a prototype cooked and eaten in London two years ago that cost £215,000 to make.

The head of the new firm set out his plans to BBC News ahead of a symposium, external on developing the technology.

Peter Verstrate said: "I feel extremely excited about the prospect of this product being on sale. And I am confident that when it is offered as an alternative to meat that increasing numbers of people will find it hard not to buy our product for ethical reasons".

The lab-grown burger was developed by Prof Mark Post at his laboratory in Maastricht University, The Netherlands.

"I am confident that we will have it on the market in five years," he said. He explained it would be available as an exclusive product to order to begin with but would be on supermarket shelves once a demand had been established and the price comes down.

The burger is made from stem-cells: the templates from which specialised tissue such as nerve or skin cells develop.

Most researchers working in this area are trying to grow human tissue for transplantation to replace worn-out or diseased muscle, nerve cells or cartilage.

Prof Post, however, used them to grow muscle and fat for his burger.

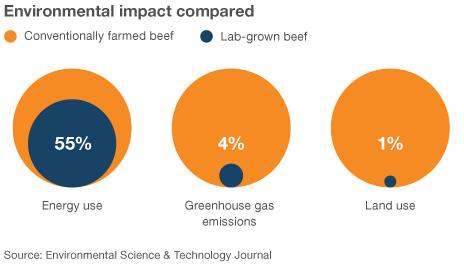

An independent study found that lab-grown beef uses 45% less energy than the average global representative figure for farming cattle. It also produces 96% fewer greenhouse gas emissions and requires 99% less land.

The motivation for the research is to find ways of keeping up with the growing demand for meat. Traditional farming methods will need to use more energy, water and land - and the consequent increase in greenhouse gas emission will be substantial.

The process starts with stem cells being extracted from cow muscle tissue. In the laboratory, these are cultured with nutrients and growth-promoting chemicals to help them develop and multiply. Three weeks later, there are more than a million stem cells, which are put into smaller dishes where they coalesce into small strips of muscle about a centimetre long and a few millimetres thick.

The strips are then painstaking layered together, coloured and mixed with fat.

The resulting burger was cooked and eaten at a news conference in London two years ago.

One food expert said it was "close to meat, but not that juicy" and another said it tasted like a real burger.

Mr Verstrate told BBC News that it was a proof of principle but not yet a finished product.

"It consisted of protein, muscle fibre. But meat is much more than that it is blood, its fat its connective tissue, all of which adds to the taste and texture".

"If you want to mimic meat you have to make all those things too - and you can use tissue engineering technologies - but we hadn't done that at the time".

The company which he has formed with Prof Post and Maastricht University, called Mosa Meat, plans to develop lab-grown minced meat that is as tasty as the real thing and costs the same.

Prof Post and his team have made progress in the past two years - but to develop a commercial product in five years he decided he had to ramp up the research.

Mosa Meat will employ up to 25 scientists, lab technicians and managers. One of the key objectives will be to find ways of mass producing the meat.

The researchers will also investigate ways of making chops and steaks using 3-D printing technologies - but that is likely to take longer to commercialise.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published5 August 2013

- Published19 February 2012