Copenhagen ghosts haunt climate talks

- Published

- comments

UN climate chief Christiana Figueres and French foreign minister Laurent Fabius are hoping that talks will stay on track to secure a deal in Paris

"I already seen that movie, it doesn't end well, it doesn't, it gets really nasty." So said Venezuelan negotiator Claudia Salerno in a tense session here at the Bonn climate talks on Thursday evening.

"I hope this is not going to be just a really, really nasty second Copenhagen," she said to sustained applause.

Yes Claudia mentioned the C-word that was on everyone's minds here in Bonn.

Copenhagen. The city where aspirations for a strong, global deal on climate change came to nothing, external in the chilly Danish capital, back in 2009.

Despite the attentions of the superstars of global politics, including the freshly minted President Obama, delegates were unwilling to go along with a deal that had been constructed by a small cohort of countries behind closed doors.

What do nations want from COP 21?

Fast forward six years and countries have once again rounded up enough momentum to have a crack at the seemingly impossible - getting unanimous agreement from 195 parties on a long-term climate deal that will have significant implications for their economies and populations.

Putting the climate humpty dumpty back together has involved understanding exactly what went on in Copenhagen, and attempting to do the opposite.

Where Copenhagen tried to impose a deal from the top down, the proposed Paris accord would be from the bottom up - countries themselves would decide how much they could cut their emissions and change their economies.

Protestors in Bonn want climate diplomats to take action to keep temperatures from rising 1.5 degrees C

And right up to the start of this week, there was general agreement that things were moving very much in the right direction. China and the US staged a well-choreographed love-in on climate change, and over 150 countries came forward with their detailed plans.

In fact the less that was actually written down, the more agreement there seemed to be.

Juddering halt

Unfortunately that dream like state came to a juddering halt when the parties arrived here in Bonn.

Having tasked the co-chairs of the talks with producing a draft of a new deal, there was howls of indignation when the 20-page document was actually published.

Developing countries were incandescent, especially on the question of finance to help the poorer countries cut their carbon and cope with the impacts.

There were accusations of apartheid like tactics from the South African head of the main group of poorer nations, called the G77 and China.

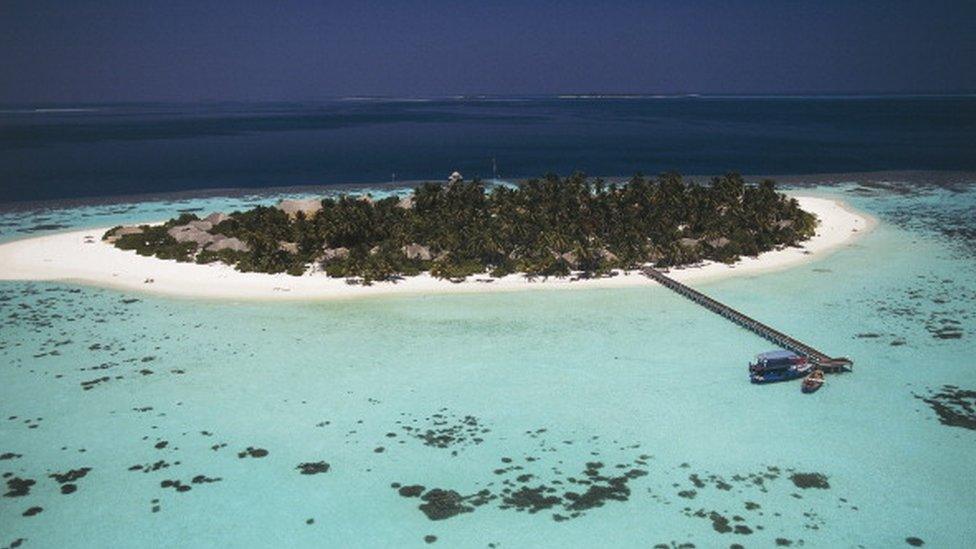

Climate change is a pressing issue for island states such as the Maldives

After a late night session, extra pages of text were re-inserted.

But the issue of trust between the countries had taken a bit of a beating.

"We began with a draft that didn't reflect developing countries' views and lost a day putting them back in," said Amjad Abdulla of the Maldives and chair of the Alliance of small Island States.

"If we want to avoid another Copenhagen in Paris we'll need to take this lesson to heart."

Things got worse later in the week when a meeting of the parties started without the chair of G77 group.

Ambassador Nozipho Mxakato-Diseko, was seething about the perceived snub.

"You cannot wish the group away, we are not an inconvenience to be ignored!" she told the assembly.

Key elements of the Copenhagen deal:

No reference to legally binding agreement

Recognised the need to limit global temperatures rising no more than 2C above pre-industrial levels

Developed countries to "set a goal of mobilising jointly $100bn a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries"

On transparency: Emerging nations were to monitor own efforts and report to UN every two years. Some international checks

No detailed framework on carbon markets - "various approaches" were to be pursued

Another sore issue was the question of observers. Japan had asked that members of non-governmental organisations and civil society groups be excluded to allow real negotiations to begin.

Cue further anger from Venezuela's Claudia.

"Why observers were taken out why at this stage when we were so close? I am just maybe disappointed by the whole thing, I felt we were going in a different direction."

Many delegates said that they felt the chill, cold hand of history.

There were some echoes of the bitter divisions between rich and poor nations, that have again and again sabotaged efforts to curb climate change.

Many others, to be fair, felt that despite the mood, things were in a far better place than they were in the days before Copenhagen.

Everyone still believes in a deal and they are working towards that goal.

But all the grandstanding had eaten into two of the things in remarkably short supply here in Bonn, trust and time.

Australian delegate Peter Woolcott, stressed that this meeting really had to deliver a text that ministers could understand.

"We do look forward to working constructively to working with parties to reach an ambitious overall agreement in Paris," he said.

"But we are a long way from that at this point."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrath, external

- Published23 November 2015

- Published22 October 2015

- Published22 October 2015

- Published16 September 2015