The gloomy Arctic seed bank that's key to future crops

- Published

- comments

The forbidding entrance to the Global Seed Vault on the Arctic island of Svalbard

What happens if war or global warming threaten the key plants that the world depends on for food? A consortium of scientists is running what it believes is an answer: a deep-freeze for thousands of seed samples that is meant to serve as a back-up to cope with the worst-case scenarios. The Global Seed Vault is buried inside a mountain on the Arctic islands of Svalbard and science editor David Shukman was allowed inside.

It's an eerie feeling approaching what's meant to be the safest place on the planet.

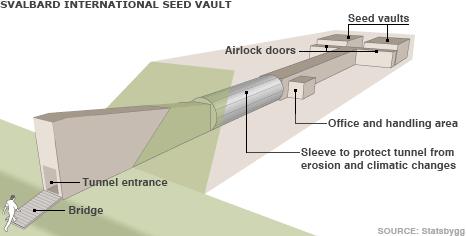

High on a wind-blasted Arctic mountain, a stark concrete doorway leads to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, external, a store to ensure the survival of the world's most precious plants.

Designed to cope with the most pessimistic nightmare of an apocalypse, a day spent here is not destined to be uplifting.

The very first barrier to entry is the sheer remoteness of the location - the Svalbard islands sit just 800 miles or 1,300 km from the North Pole.

And although there are plenty of flights from mainland Norway, and Arctic adventures are growing in popularity, the population is sparse and mass tourism is not on the cards.

Next comes an unintended hazard - a sheet of rock-hard ice covers the small car park as we arrive. Each step is treacherous. I picture the highly unlikely scenario of a rampaging mob threatening the place but failing to remain upright.

Keys to the kingdom

Seeds from more than 5,000 species of crops are held in the vault

The outermost door is fashioned out of steel but is opened by a disappointingly ordinary key - the kind that most of us use at home.

What happens if you lose it? For some reason, my mind is on a cynical track today. The answer is obvious: we have spares.

The first steps inside take us out of a piercing wind and into an atmosphere of extreme quiet. A line of safety helmets is waiting to be worn.

Another door opens on to a tunnel that gently descends deeper into the mountain. The temperature is minus 4C and we're now in permafrost where the ground around us never thaws.

Most of the tunnel is lined with concrete but further inside the rock face is bare. Our voices start to echo.

The concept of the project is simple: imagine everything that could go wrong with the world's key food crops and make sure samples of them are untouched here.

So the entrance itself is 130m above the sea - that's comfortably above the most horrific projections for how the oceans could rise if there is a total melting of the polar ice-caps in the coming centuries.

Being carved out of the rock should also make the seeds immune to war. Svalbard is a very long way from any military conflict but let's say one blows up in the Arctic - which is not totally inconceivable - and an utterly random weapon lands just here. In theory, it should not get through.

As I hear this, I'm reminded of a visit I made many years ago to Norad, external, America's air defence control centre buried inside Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado.

That was on a far bigger scale - we were driven right inside the mountain by bus - but the thinking is along the same lines. Thick rock offers the best insurance against missiles.

At this point, we arrive at yet another door, this one white with frost. The temperature is falling. Stepping through brings us into what is called the "cathedral", a vast cavern that leads to the actual store-rooms themselves.

Above us run the silver ducts of the cooling system. Crystals of ice are glinting on the rock walls. We are now on the brink of the holy of holies.

Boxes from North Korea

One more door lies ahead. It is thickly encrusted in ice. The air beyond is kept at minus 18C. We're dressed for it but any bare skin quickly chills and my biro jams almost immediately. We film as fast as we can.

The store has rows of shelves, each one crammed with large plastic containers of the sort you might use to keep files or move house. Inside are tiny packets that hold the seeds themselves - more than 865,871 packets in all, representing more than 5,000 species and nearly half of the world's most important food crops.

The labels are fascinating - there are seeds from Africa, Asia and America. There are also boxes from North Korea - that's a big surprise.

But the story behind the containers from Syria is the most moving. A regional centre researching agriculture in dry areas was based in Aleppo. But power cuts and then the civil war made the work there untenable and hazardous so the seeds were taken on the long journey here.

That's exactly what this place was designed for. Most countries have their own stores of key plant varieties and the Global Seed Vault is meant to work as a back-up to those back-ups.

Where floods have threatened national seed stores, or where industrial-scale agriculture has reduced genetic variation so much that pests could be catastrophic, or where projections for climate change look threatening to food supplies, this place starts to make sense.

The vault is gloomy, and you need a dark imagination to come up with motivations for it, but the sheer number of countries and institutions using it is its own justification.

The main tunnel in the seed vault stretches 115m into the mountain

And earlier this month - far earlier than anyone expected - came the first example of the vault really doing its job, external.

Some of the Syrian seeds - including ancient and potentially sturdy varieties of wheat, barley and chickpeas - were extracted from the deep-frozen shelves because they were needed back in the Middle East.

In all, 128 boxes - out of a total of 350 originally sent from Aleppo - were carried back through all the doors, up the tunnel and over the dangerous ice-patch to be flown to Lebanon and Morocco.

The seeds are derived from plants cultivated in some of the first examples of farming, right back in the crucible of agriculture, the Fertile Crescent, external, and they will now be planted to produce duplicates.

Soon there will be farmers in the Middle East whose future crops may produce greater yields or be more resistant to drought, all because packets of seeds were at one stage kept safe in a secure bunker on a lonely mountainside in the distant Arctic.

Follow David on Twitter @davidshukmanbbc, external.