COP21: Fine words but divisions run deep

- Published

- comments

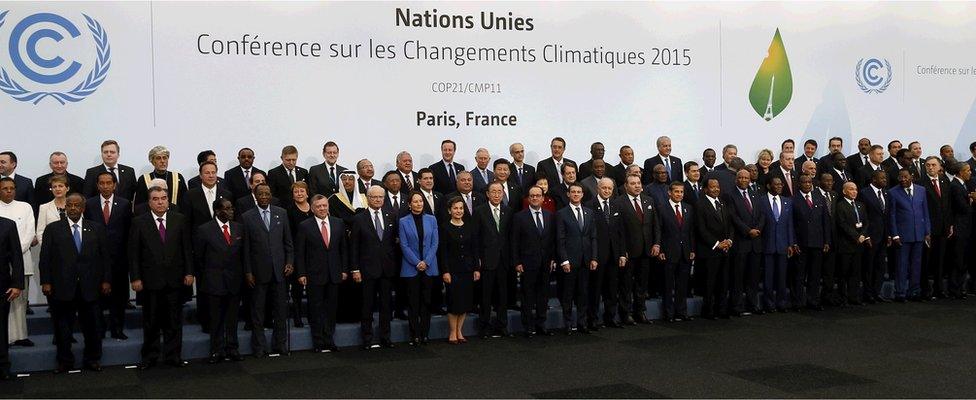

Handshakes and warm words on the opening day: Now the hard work begins

"We are on the front line; we will fall. It must not happen to anybody else," says the President of Kiribati, Anote Tong.

For our interview, he has come out into the main conference centre, away from the leader's compound, where heads of state and prime ministers have been speaking to delegates here all through the day.

President Tong called for a strong, legally binding deal and a moratorium on coal mining. It's too late for his people, he says. They are actively preparing to evacuate the coral atolls that they call home.

He took great encouragement from the speeches of the other leaders. This might just be the time when the world finally acts, he said.

Although they were supposed to talk for just three minutes each, most of the leaders took as much time as they wanted. And you wonder why this process has lasted 20 years?

So what can we glean from the warm words and good intentions of the leaders? Is the President of Kiribati right to be optimistic?

There are certainly positive omens. Leader after leader sang the same hymn - climate change is a huge challenge, only co-operation on a global level can solve it, and my country is doing great!

Still there were obvious divisions.

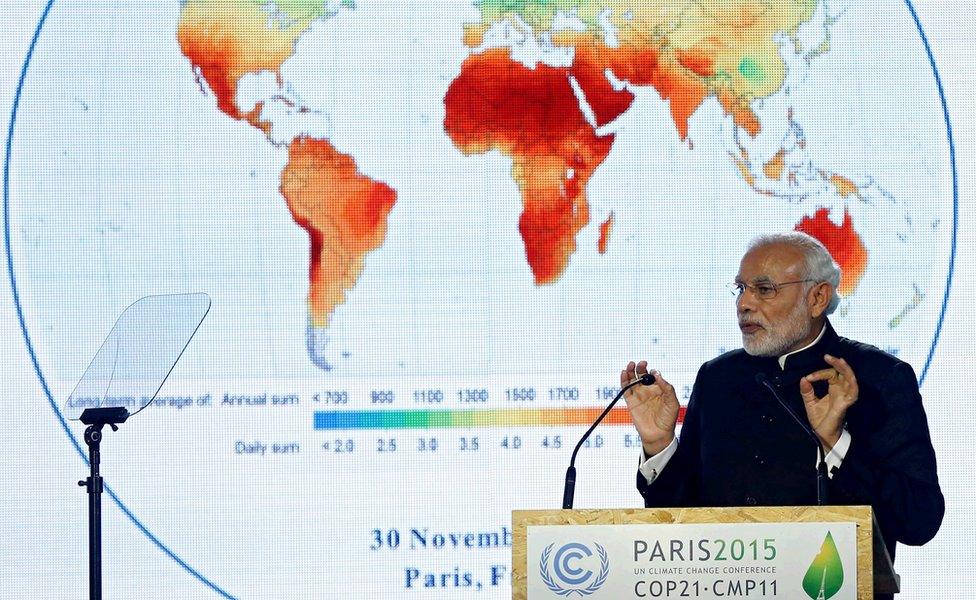

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has drawn clear lines in the sand

President Obama, a long-time supporter of strong action, spoke with sombre determination. Success here is crucial for his long-lasting legacy.

But his commitment to an agreement is not a commitment to a legally binding treaty. He knows he won't be able to sign such a document as it would need ratifying by the US Senate. And they are not keen, to say the least.

Many other leaders stressed the need for just such a binding agreement - even President Vladimir Putin.

After he explained how Russia had managed to grow their economy and cut emissions (who knew?), he called for a binding target of 2C in the growth of global temperatures.

China's leader, Xi Jinping, likewise called for a strong deal.

But he used some telling phrases that suggest delivering this child of Paris will not be easy.

The principal of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities must be adhered to, he said.

In climate speak, that's a reference to the origins of the UN Framework Convention back in 1992, which divided the world into Annex 1 and Non-Annex 1 countries - essentially rich and poor.

Key issues

Major points of contention include:

Limits: The UN has endorsed a goal of limiting global warming to no more than 2C over pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. But more than 100 poorer countries and low-lying, small-island states are calling for a tougher goal of 1.5C.

Fairness: Developing nations say industrialised countries should do more to cut emissions, having polluted for much longer. But rich countries insist that the burden must be shared to reach the 2C target.

Money: One of the few firm decisions from the 2009 UN climate conference in Copenhagen was a pledge from rich economies to provide $100 billion (93 billion euros) a year in financial support for poor countries from 2020 to develop technology and build infrastructure to cut emissions. Where that money will come from and how it will be distributed has yet to be agreed.

Mr Xi, like Mr Narendra Modi of India, wants the richer countries to do the bulk of the carbon-cutting and provide the bulk of the financial support.

While 60-65% of emissions now come from developing countries, China and India say that richer countries must still be held to their historic responsibility. Now is not the time to change that, they argue.

Mr Xi also said that the richer countries should honour the commitment made in 2009 to provide $100bn of climate finance by 2020. And they should provide more in the years following.

These wrangles are well known and there was little new in terms of movement by any of the parties here in Paris on the opening Monday of the conference.

Progress may or may not happen over the next two weeks.

One negotiator told me the whole idea was for the leaders to come, speak and happily be on their way without toppling this carefully constructed applecart.

Unlike in Copenhagen in 2009.

"The leaders fully understand the political nature, the political difficulties. They are coming here to provide manoeuvring guidance," he said with a hint of irony.

"And we as negotiators will then have to fix it."

UN climate conference 30 Nov - 11 Dec 2015

COP 21 - the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties - will see more than 190 nations gather in Paris to discuss a possible new global agreement on climate change, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the threat of dangerous warming due to human activities.

COP21 live: The latest updates from Paris

Explained: What is climate change?

In video: Why does the Paris conference matter?

More:, external BBC News special report

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.