Peake: What will the astronaut be doing in space?

- Published

After all the drama of the launch, what will Tim Peake actually do during his six long months on the International Space Station?

After seeing the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield performing with his guitar or Scott Kelly of Nasa doing airborne somersaults, many might wonder if the ISS has a serious point.

The reality is that everyone sent up there faces a very busy timetable which involves managing a range of experiments that make use of the state of weightlessness.

The space station is a giant laboratory and every inhabitant is expected to get involved in the research.

Just by being in space, Tim himself will serve as a lab rat, allowing his body to be monitored in great detail - with 23 different sets of measurements in all.

By the end of his mission, he will be all too familiar with the regular processes of gathering samples of his blood and urine. Space research is not for the squeamish.

Blobs of metal

But if there is ever to be a long trek through space to Mars or even beyond, medical knowledge of how humans cope will be essential.

So some of the research is aimed specifically at gaining new insights that will benefit future generations of spacefarers while other experiments are designed to have a relevance to life here on Earth.

One European Space Agency project is investigating the properties of metals in a level of detail that cannot be matched down on the ground because of the influence of gravity.

Prof Mike Cruise of the University of Birmingham, who chairs ESA's human spaceflight science advisory committee, told me that the work "sounds really obscure but could have quite an effect on all our lives".

Until now, any analysis of how metals behave is almost guaranteed to be undermined because gravity will force the sample to touch the walls of whatever container is being used and that means it will collect impurities.

So the Electromagnetic Levitator experiment - in the European Columbus module - has a clever technique for allowing blobs of metal to be heated and then cooled while being suspended in the air.

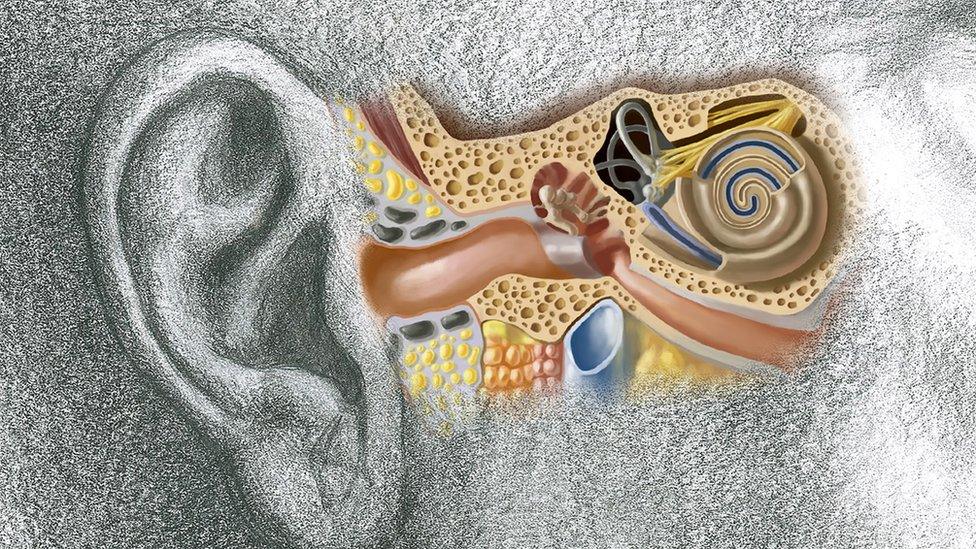

One of the experiments will help understanding of how the inner ear works

While this happens, measurements are made of the characteristics of the metal, all without the complicating effects of gravity risking the integrity of the research.

Prof Cruise said: "If you look around your car, it probably has 20 or even 40 items made by casting molten metal into a mold - a process that requires huge knowledge of the properties, of how sticky or viscous the metal might be.

"If we got better measurements, our casting could become far more efficient with fewer parts with holes in them - this seemingly innocuous experiment that could have a pretty huge industrial impacts."

So the aim is to generate a far better understanding of key materials, and scientists from the Universities of Greenwich and Leeds are among those making use of the results.

Another project, called Fluid Shifts and managed by Nasa, is exploring the question of pressure within the brain.

Astronauts have often reported problems with their vision and the assumption is that this is the result of fluids shifting within the body and particularly moving towards the head.

Researchers at University Hospital Southampton NHS Trust have found a connection between the brain and the ear, and a better grasp of how this process works could help with a new technique for assessing brain pressure by taking measurements in the ear.

Early days

A UK company, Marchbanks Measurements Systems, has come up with a device that can detect slight changes in the inner ear.

The company's founder Dr Robert Marchbanks told us:" It is crucial to the understanding of how brain pressure changes. It is a different environment, there is no gravity but that is important to our understanding of brain pressure."

And while some research is aimed at improving human health, another focus is on helping answer the fundamental question of whether we are alone in the universe.

Since micro-organisms such as bacteria have been found thriving in the most inhospitable corners of Earth - from the deep-frozen Antarctic to boiling hydrothermal vents - the next step is to explore how they cope with space.

Photographers took pictures as the Soyuz TMA-19M spacecraft lifted off

If it is the case that life got started here because rudimentary forms of it were delivered by a colliding asteroid or comet, the obvious question is whether it is possible that life-forms could survive in an icy vacuum or fiery descent through the atmosphere.

So a series of experiments called Expose, involving the University of Edinburgh, places different organisms outside the space station to see their response to cosmic rays, solar radiation and intense temperature changes.

It is only in the last three to four years that the ISS has been able to host so much research.

Financial problems, and the loss of the US space shuttle Columbia in 2003, meant that construction took far longer than planned - and for years the few crew on board could spare little time for science.

That has now changed and the first results from ISS experiments are being released, but it is still early days to judge the space station's value to research.

Prof Cruise said: "There is a lot of good science. It's not all headline Nobel Prize work, but the nature of the experiments means it would never get into Nobel territory.

"It's going to take us another five years or so to judge what that scientific contribution has been".

The ISS was conceived at the end of the Cold War as a way of cementing friendship between the United States and Russia and to keep Russian scientists from being lured away to countries such as Iran.

Now it's become a platform for international research, and a novice British astronaut will play his part.

Tim Peake in space: Want to know more?

Special report page: For the latest news, analysis and video

Video: How the view from space affects your mind

Explainer: The journey into space

Social media: Twitter looks ahead to lift-off

- Published15 December 2015

- Published15 December 2015