Tim Peake: How he gets to space and back

- Published

The Soyuz-TMA can transport up to three crew members and a small space for cargo

UK astronaut Tim Peake is returning to Earth after a six-month stay on the International Space Station (ISS). Since the space shuttle's retirement, the Russian Soyuz system is now the only way for crew members to get to and from the ISS.

The basic design for the Soyuz capsule was laid down as far back as the 1960s. It was originally intended to serve as the craft that would carry cosmonauts to the Moon.

When the US beat them to the lunar surface in 1969, the USSR's lunar programme was scrapped. But the Soyuz was retained, and became the Soviet - and subsequently Russian - vehicle of choice for launching humans to low-Earth orbit.

It was the craft that carried the first crew to the International Space Station in 2000, and has been the only craft ferrying humans to the orbiting outpost since the retirement of the US space shuttle in 2011.

The spacecraft

This Soyuz-TMA simulator, used for training, replicates the interior of a real capsule

The current version, known as the Soyuz-TMA, can transport up to three cosmonauts and a limited amount of cargo to and from the ISS. At least one Soyuz is docked to the space station at all times to be used as a lifeboat in an emergency.

At one end of the spacecraft is the spherical orbital module. It's about the size of a large van and provides extra living space for the crew during flight. It can be used to store supplies and other cargo, such as experiments, and there's also a toilet.

The orbital module contains the mechanism used to dock with the space station and the hatch that allows crew members to enter the ISS.

Each seat in the Soyuz is individually moulded to the crew member

The craft's mid-section is known as the descent module, and is where crew members sit during launch and the journey back to Earth. It contains the spacecraft's controls and displays, including a periscope that allows the crew to see the docking target on the ISS.

The seats have custom-fitted liners, individually moulded to each person's body. This is designed to help cushion the crew members when they land on Earth after a mission.

The third module is known as the instrument module. It contains the thrusters, oxygen and propellant tanks, communications equipment and the onboard computer.

The rocket

The Soyuz rocket is moved on a transporter at Baikonur Cosmodrome

Launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, the 50m-high launcher consists of three sections, or stages. The first stage consists of four identical liquid-booster rockets. These are strapped around the core, or second, stage. The third, or upper, stage carries the Soyuz spacecraft.

The vehicle uses refined kerosene and liquid oxygen as fuel and can deliver payloads of more than seven tonnes - about the weight of a small lorry - into orbit.

The Soyuz-TMA spacecraft, which carries the crew, sits atop the launcher - covered by a protective shroud, or fairing.

Baikonur Cosmodrome

The world's first operational space launch centre, built by the Soviet Union in the late 1950s.

It is located on the sparsely populated desert steppe of Kazakhstan, about 200km east of the Aral Sea

Baikonur was the launch site for the world's first satellite, Sputnik 1, along with the first human mission - Vostok 1

A purpose-built city supports the launch facility - formerly Leninsk, it was renamed Baikonur in 1995.

Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, the Russian continued to lease Baikonur from the Kazakh government

Launch and docking

The 50m-high rocket can lift about seven metric tonnes into orbit

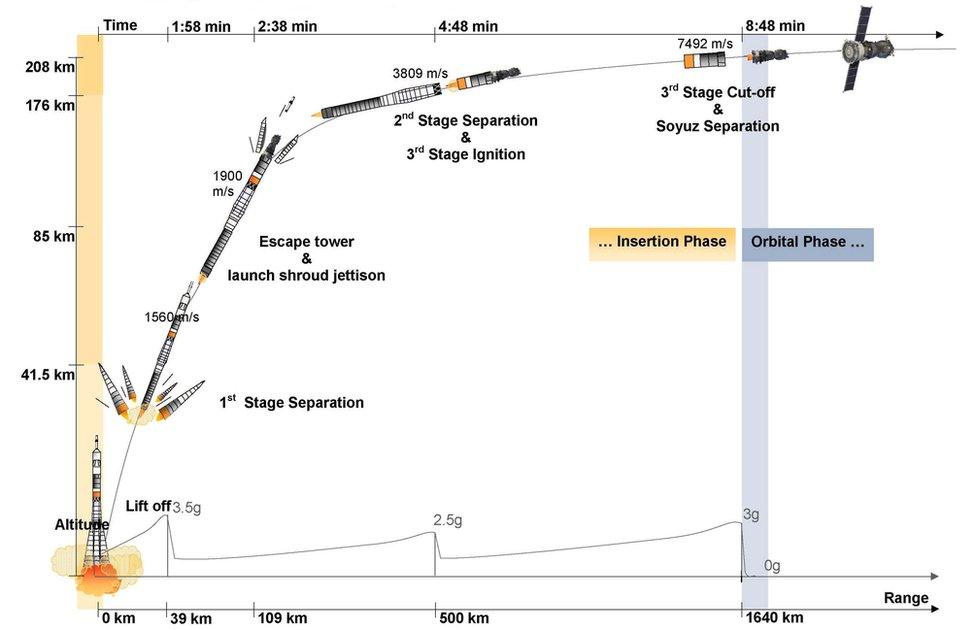

Crew members enter the spacecraft two-and-a-half hours before launch to prepare it. At T-minus zero, the four boosters and core engine ignite, propelling the rocket into the air. About two minutes into the flight, the four booster rockets are jettisoned.

The core stage keeps firing, until it too separates at about 4 minutes 48 seconds after launch. A third stage engine then propels the Soyuz to its desired orbit at an altitude of some 220km. During the nine-minute sequence, crew members have to withstand forces up to three-and-a-half times their bodyweight.

The spacecraft then has to perform five engine burns in order to catch up with the ISS. This generally takes six hours, but if things don't go as planned, mission control may decide to fall back to an alternative two-day transfer mode.

Rendezvous and docking with the space station is automated by the onboard computer. It keeps track of the positions of the Soyuz and ISS using measurements from mission control and a radar system called Kurs. However, crew members closely monitor the process and have the ability to intervene or take over manual control if required.

A docking probe on the end of the Soyuz inserts into a port on the ISS to anchor the craft together

During the final approach, a docking probe on the end of the Soyuz inserts into a cone on the ISS. Once "capture" is confirmed, the docking probe retracts, bringing the two vehicles together. A series of hooks and latches then close over, securing the Russian capsule to the ISS.

Once a tight seal is confirmed, the air pressure in the Soyuz is equalised with that of the ISS and the hatch is opened, so the new arrivals can enter the station.

At least one Soyuz is docked to the ISS at any one time to act as an emergency "lifeboat"

Undocking, re-entry and landing

When crew members are ready to return to Earth, a command is given to start opening the hooks and latches that hold the Soyuz to the ISS. The spacecraft then separates from the space station at a graceful speed of 10cm/s (4ins/s). Once the Soyuz has reached a distance of 20m (66ft) the Soyuz fires its thrusters for 15 seconds.

When the capsule reaches a distance of 19km (12mi) from the ISS, the Soyuz makes its main "de-orbit burn", firing the engines for 4 minutes, 21 seconds to begin the return to Earth. The descent module carrying the crew separates from the empty orbital module which burns up in the atmosphere.

The descent module touches down on the Kazakh steppe

About 15 minutes before landing, the capsule deploys a drogue parachute to slow its descent speed from 230m/s (755 ft/s) to 80m/s (262 ft/s). The main parachute is then released, cutting the capsule's speed to 7 m/s (24ft/s) and shifting it to a vertical position.

Six engines fire on the underside of the capsule to cushion the craft just before it thuds down on the Kazakh steppe.

A recovery and rescue team then arrives to extract the crew members.

A recovery team is on hand once the crew members land on the Kazakh steppe