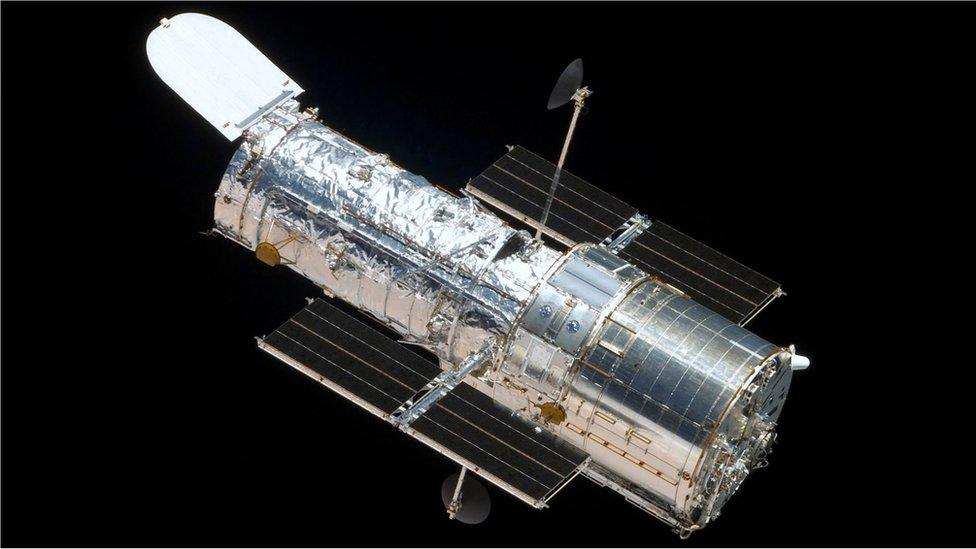

James Webb: Hubble successor maintains course

- Published

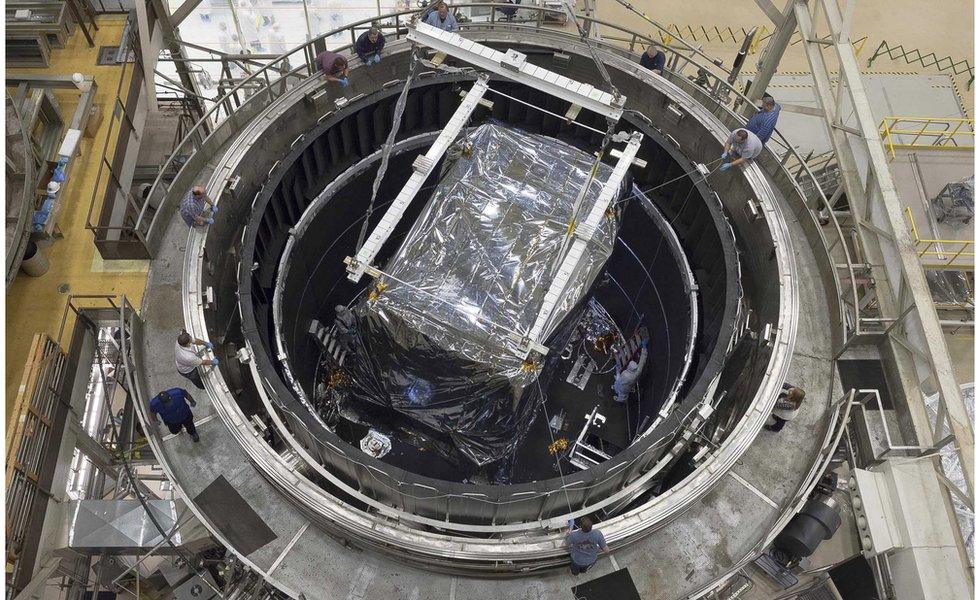

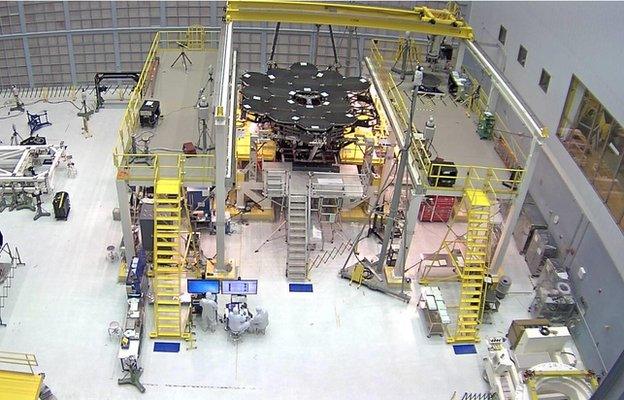

Soon to emerge: The instruments were placed in the Goddard vacuum chamber for testing late last year

The successor to the Hubble Space Telescope is reaching some key milestones in its preparation for launch in 2018.

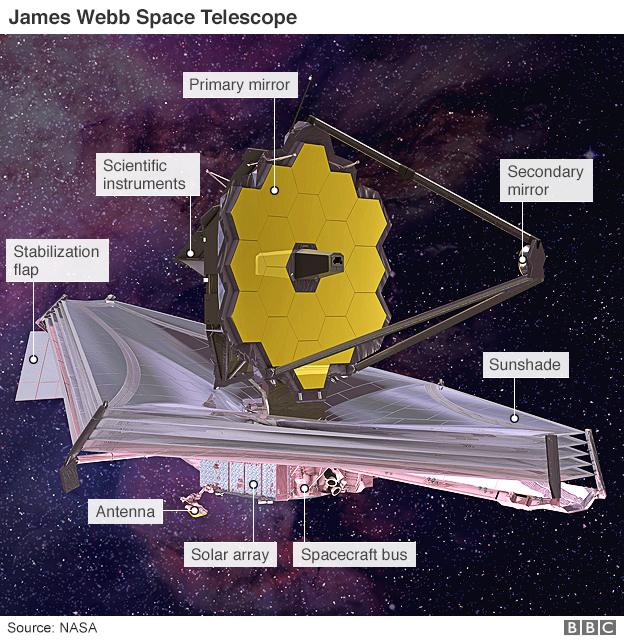

Engineers are about to complete the assembly of the primary mirror surface on the James Webb Space Telescope, external.

They are also winding up the final deep-chill calibration tests on the observatory's four instruments.

The US space agency-led project is now on track to make rapid progress in the coming months.

The major components of JWST, which have been years in the design and fabrication phase, will at last be integrated into their flight configuration.

With margin still in the programme to cope with any unexpected problems, everything currently remains on course for an October 2018 lift-off atop a European Ariane rocket.

"We keep our fingers crossed, but things have been going tremendously well," said Nasa's JWST deputy project manager John Durning.

"We have eight months of reserve; we've consumed about a month with various activities," he told BBC News.

"But I think we've really befitted from the 'pathfinder' work we've done in the last year or so where we practised activities, and that's allowed us to run like a well-oiled machine."

Webb is a joint venture between Nasa and its European and Canadian counterparts.

It will go in search of the very first stars to shine in the Universe, external.

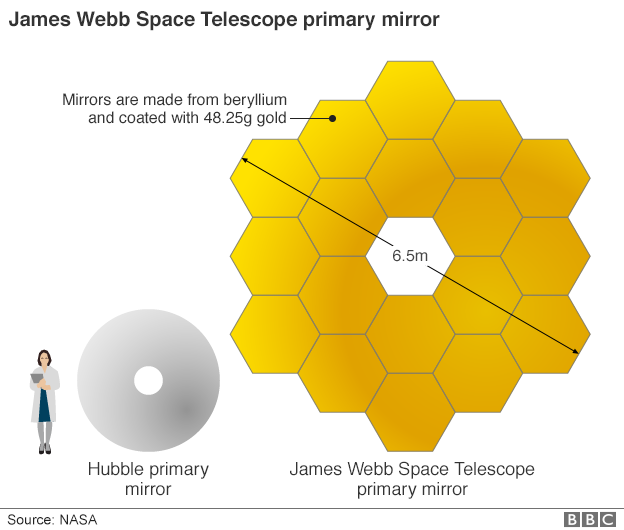

To achieve this ambition, it will deploy a 6.5m-wide mirror, giving the observatory roughly seven times the light-collecting area of Hubble. And allied to instruments that are sensitive in the infrared, Webb will be tuned to detect the faint, "stretched" glow of objects that originally shone more than 13.5 billion years ago.

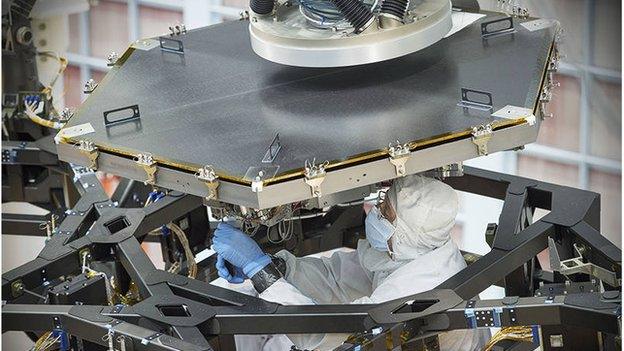

Recent weeks have seen engineers gluing the beryllium segments of the main mirror into their supporting backplane structure.

In the next few days, the last two of 18 hexagons will be lowered into position for secure attachment.

Meanwhile, down the corridor from the Webb cleanroom at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, the instruments are about to emerge from their latest "cryo-vac" campaign.

Since October, the quartet - NIRCam, external from the US, NIRSpec and MIRI from Europe, and the Canadian FGS/NIRISS, external - have been sealed in an airless chamber and taken down to the temperatures at which they must operate in space. This is in the realm of 40 kelvins, or -233C.

US, European and Canadian teams have been working around the clock, putting the instruments through their paces, presenting them with "artificial stars" that simulate the kinds of objects they will eventually get to probe on the sky.

The oversight continued through the blizzard that hit the American East Coast over the weekend.

Each beryllium mirror segment is bonded into place

Two remaining segments await attachment to the support backplane

Calibration data has been acquired that will be critical to the proper operation of JWST when it starts peering deep into space for real in two-and-a-half-years' time.

The cryo-vac session has also permitted a number of modifications made to underperforming parts of instruments to be thoroughly checked out.

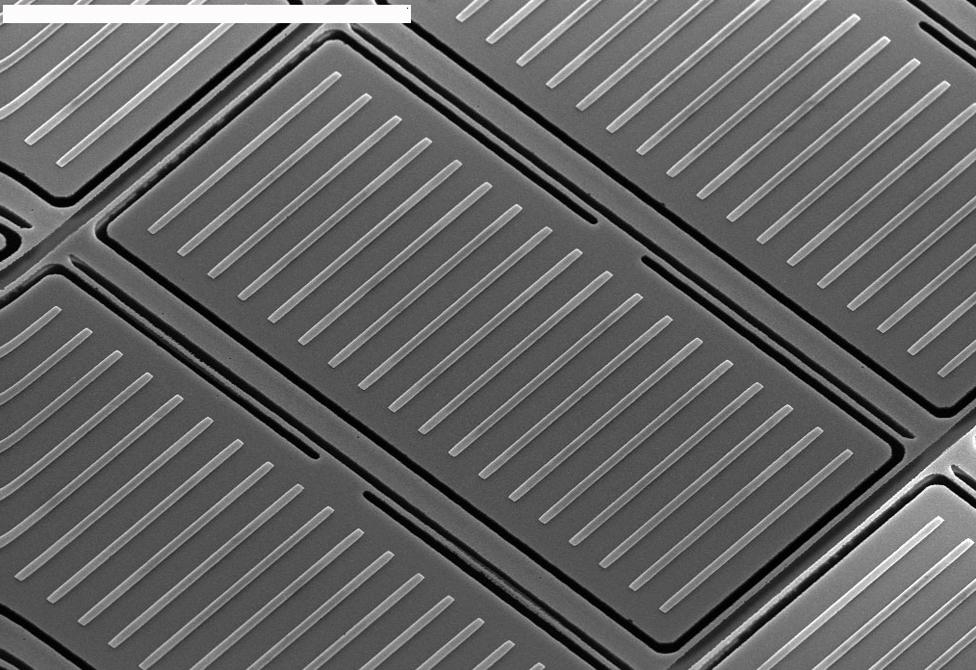

Before going into the chamber, some degraded detectors and electronics were replaced; so too was a troublesome micro-shutter array in NIRSpec intended to help tease apart the colours of stars and galaxies.

Some of the array's 250,000 tiny "doors" had the annoying habit of sticking open or closed when subjected to the simulated noise of an Ariane launch.

The replacement hardware also suffers from this behaviour when put in an extreme acoustic environment, but the overall performance is much improved and well within the threshold demanded. And, certainly, the situation has not worsened during the cryo-vac testing.

The European Space Agency's JWST project scientist Pierre Ferruit explained: "One of the strong points of NIRSpec is to be able to view multiple objects at the same time, and, of course, the more operable shutters we have, the more objects we can observe at once. And right now we can meet our scientific objectives. Right now, we have just under 90% operable shutters, and that's OK."

The microshutter doors selectively allow light through to NIRSpec's detectors, enabling the colours of particular stars and galaxies to be studied (Scalebar: 0.1mm)

If sticky shutters are no longer the issue of concern they once were, there remains some anxiety over a cryocooler needed to take MIRI to even lower temperatures than its three siblings. This active chilling system is late and threatens to eat into those eight months of margin that project managers must defend or risk missing the 2018 launch date.

The latest iteration of the cryocooler is in test at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in California, and is reported to be doing well. The good news from the Goddard cryo-vac campaign is that the forward "plumbing" of this system works exactly to its specification.

"The piece of the cooler that attaches to MIRI and makes us cold was in this latest cryo-vac campaign, and that was an important step forward for us," said Gillian Wright, MIRI's British principal investigator.

"So part of the flight cooler is now integrated with MIRI. But, yes, some of the flight cooler has to be integrated with the spacecraft part of JWST, and so the two halves won't actually get connected until just before launch. That's a risk that will have to be managed.

"But the JPL tests are going well, so I don't think we're quite the concern we once were."

Engineers and scientists agreed on Friday that there was no need to extend the cryo-vac campaign any further. They will not immediately lift the lid on Goddard's vacuum chamber; they will bring it up slowly to ambient temperature, a process that will take until the second week of February.

The instruments can then be wheeled back down the corridor to begin the complex task of being joined to the mirror and its support system. This should happen around May.

Optical, vibration and acoustic tests will follow.

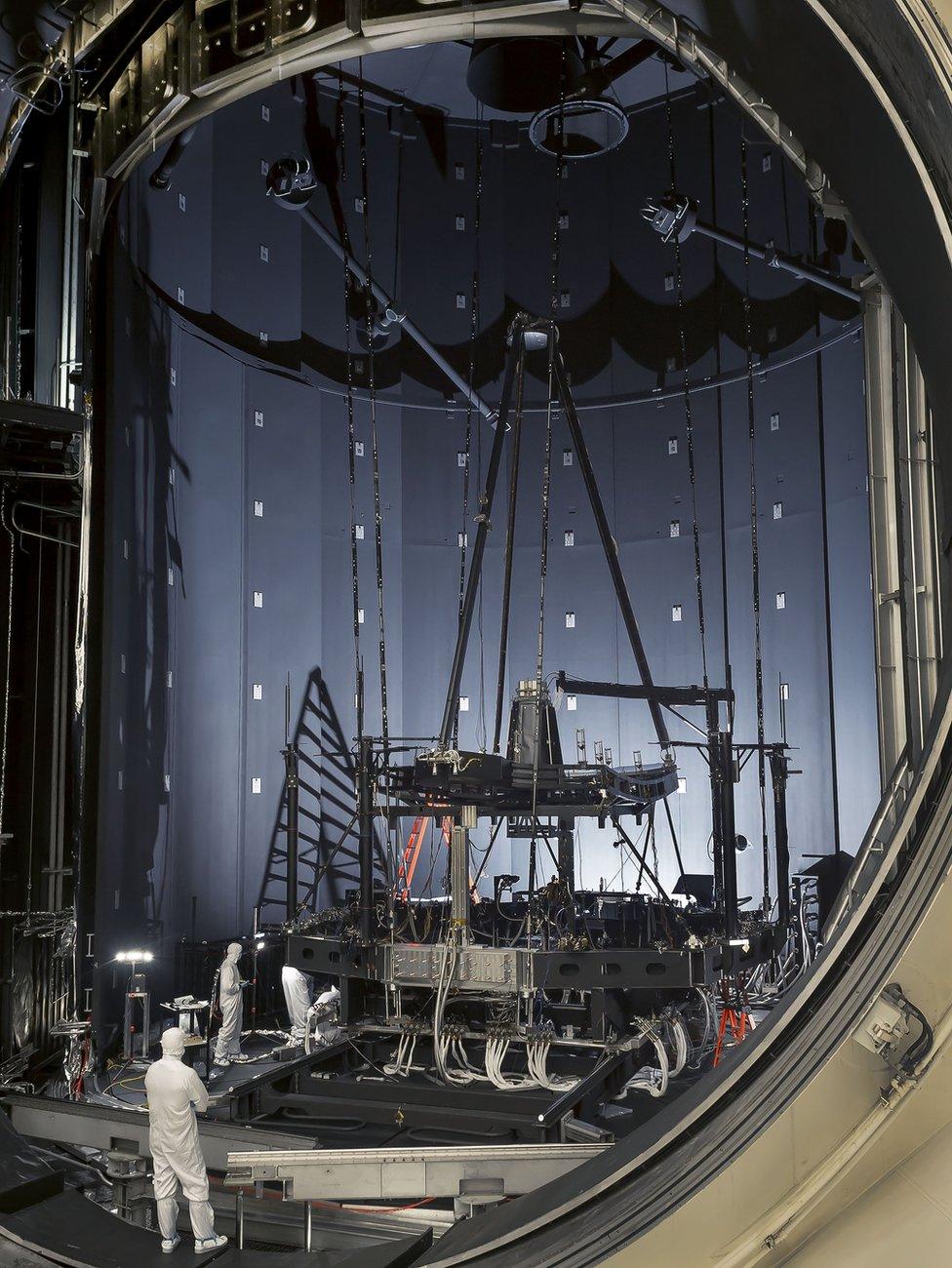

The whole train - mirror and instruments - will then ship to Nasa's Johnson Space Center for a further cryo-vac campaign in the chamber built to test the 1960s Apollo hardware. This is likely to start in a year from now.

And at some point beyond that, the attachment will take place of the spacecraft bus, which incorporates elements such as the flight computers and communications system, as well as the main part of MIRI's cryocooler.

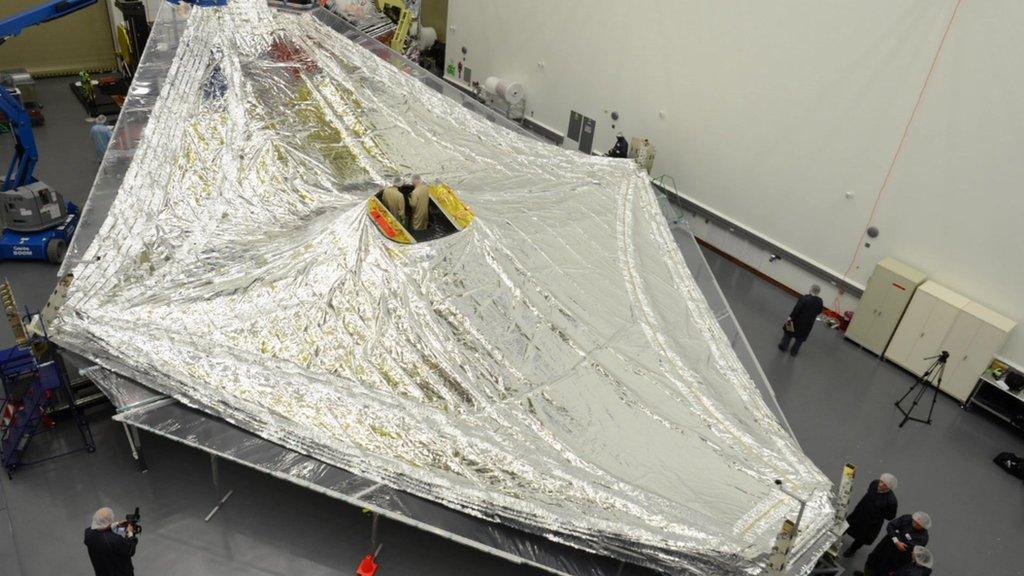

Finally, Webb will get its giant deployable visor - the structure that will shield its delicate observations from the Sun's light and heat.

October 2018 is really not that far away.

Pathfinder test: Using full-size models of hardware, engineers have been practising in the big Apollo chamber

Shielded from the Sun: JWST is an infrared telescope and must therefore be kept cold to work properly

- Published13 December 2012

- Published23 April 2015

- Published17 February 2015

- Published31 July 2015

- Published31 July 2015