Watching the heavens: The female pioneers of science

- Published

Fiammetta Wilson: She opened the door to women in professional astronomy but her name has largely been forgotten

As the bombs fell on London during the Great War, two women kept a vigil of the night sky.

Fiammetta Wilson and Grace Cook observed shooting stars - the chunks of space rock that light up the sky as they plummet to Earth.

They kept up records of meteors in what was then very much a man's world.

In 1916, the pair were among the first four women to be awarded fellowship of The Royal Astronomical Society, external - a milestone in the acceptance of women in science.

Although their names have largely been forgotten, the first female fellows of the society are being remembered 100 years on.

Dr Mandy Bailey is an astronomer at the Open University and a member of the Royal Astronomical Society council.

She says Fiammetta Wilson and Grace Cook ensured scientific work on meteor observations continued while their male colleagues were off fighting a war.

"In the years between 1910 and 1920 Wilson observed somewhere in the region of 10,000 meteors and accurately calculated the paths of about 650 of them - no small achievement!" she says.

Watching the heavens

As Mrs Cook wrote of her friend in 1921, "her dauntless spirit often enabled her to gain success where others would have failed.

Leading women in UK astronomy and geophysics today, assembled from portraits by the photographer Maria Platt-Evans

"She sometimes watched the heavens for five or six hours, when only a few stars were visible amid the clouds, and her perseverance was often amply rewarded by the detection of fireballs."

Mrs Wilson's wholehearted pursuit of science during the war led to accusations of spying.

"During the war astute special constables detected the flashlight she used for recording meteors, and severely threatened her with arrest as a German agent," Ms Cook wrote , externalafter her death.

"With zeppelins dropping bombs in the neighbourhood, Mrs Wilson calmly pursued her vigils on several occasions.

"Falling splinters from shrapnel once made things highly dangerous, but she managed to get good records."

Strange star

Wilson and Cook opened the door to women from all walks of life to become astronomers.

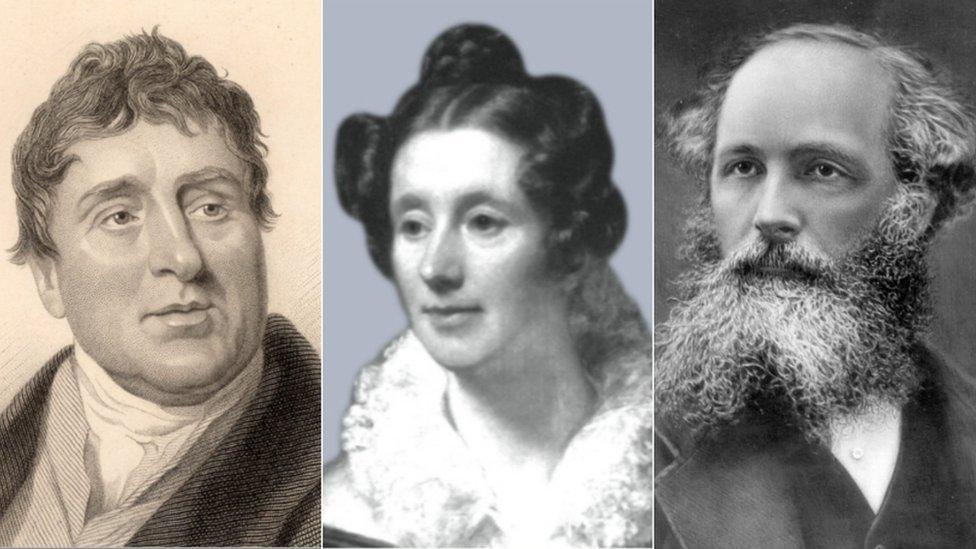

In the 19th Century, the RAS had granted honorary fellowship to famous scientists Caroline Herschel and Mary Somerville.

But the organisation had refused to allow women to become full members, arguing that fellows were described in its Royal Charter only as "he".

Solar physicist Annie Maunder was proposed for RAS fellowship in 1892 but rejected

It took the social change of the First World War and the movement of women into what were once seen as male jobs to bring change.

Women like Grace Cook had been regarded as amateurs somewhat unfairly, as they could not join professional societies or put their names to scientific papers.

Ms Cook was inspired to take up astronomy after listening to a lecture by the great grandson of Caroline's Herschel's brother - Joseph Hardcastle.

He lent her a telescope and she later returned the favour by helping to plot his finds on a star map.

In a letter, external, Ms Cook recalled a memorable night observing the sky in 1918.

"It was one of the highlights of my observing nights that on June 8th 1918 when I went out to search for slow-moving bright meteors, almost at once I spotted a strange star, twinkling violently and changing colours rapidly.

"This was at 9.30pm and I was the first astronomer in England to make the earliest observation of Nova Aquilae."

Shaping science

A century on, the proportion of women in astronomy has risen significantly.

According to the latest figures from the RAS, 7% of astronomy professors and 28% of lecturers are women.

"Females are still underrepresented, especially at senior levels, but it's getting stronger every year," says Clare McLoughlin, education, diversity and outreach officer at the RAS.

She says there is a big push to encourage young women to study physics at A Level, particularly by showing them positive role models of women in science.

But the women of 1916 - who could have been great role models in their time - sadly have largely been forgotten.

"They were known within astronomical circles but I don't think they were known to the wider public," says Ms McLoughlin.

"These women kept pushing, they kept trying and gradually won over opinions.

"They never gave up."

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published10 February 2016