Bloodhound land speed record bid delayed until 2017

- Published

Bloodhound had its static debut in London's Docklands last September

The British-led bid to break the world land speed record has been put back again, to 2017.

The Bloodhound Super-Sonic Car was supposed to go racing later this year, to try to raise the current mark of 763mph (1,228km/h) to over 800mph.

But the project does not yet have the funds needed to run the vehicle on its specially prepared track in South Africa.

It is hoped the delay will enable more sponsorship deals to be sealed.

"It's in the nature of land speed record attempts that they tend to be a bit hand-to-mouth," said Bloodhound director, Richard Noble.

"But the good thing is that we have a steady stream of offers coming in. It's hard work to get them done, and they can always collapse.

"What tends to happen is that the nearer you get to actually running, the whole thing turns. We've just got to get on with it," he told BBC News.

The car itself is virtually complete. At 13m in length and weighing more than 7 tonnes, Bloodhound had its static debut in London last September.

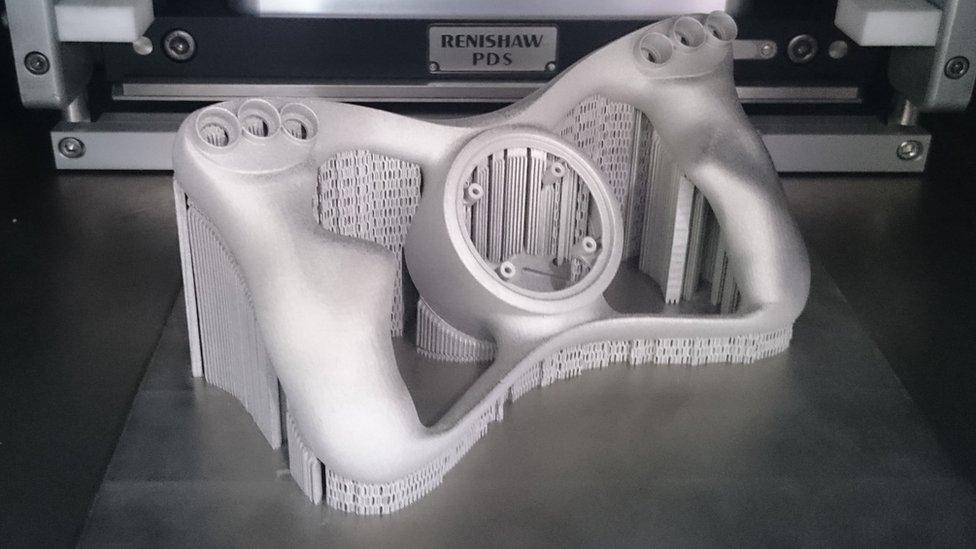

Bloodhound's rocket partner is Nammo of Norway

Its one major outstanding element is its rocket system.

This will fire in tandem with a Eurofighter jet engine to push the vehicle through the sound barrier. The ultimate goal is to go above 1,000mph (1,610km/h). This higher mark would be sought in a second year of racing, now projected to be in 2018.

The rocket motor and its pump mechanism have yet to undergo full, end-to-end testing, but even if they had, the project's present problem is really all about cash flow.

This year, Bloodhound needed on the order of £17m to mount a record bid.

The money is coming in from donors and sponsors - just not at the rate required to support a full race team at Hakskeen Pan for 8-12 weeks.

That is the amount of time it would probably take to get the car rolling on the Northern Cape lakebed, iron out teething problems, and then run at top speed.

Hakskeen Pan: A team of 35 to 40 people will operate the car in the desert for 8-12 weeks

Announced in 2008, Bloodhound was originally envisaged to be breaking the land speed record in 2011/12.

But finding an aerodynamic shape that would keep the car stable on the ground took far longer than expected.

Subsequent delays were announced in 2013 and 2015, as the team grappled with various other design and build issues on the highly complex machine.

"The sponsors have been great; they understand what this is all about. But we really do need to get on with it now or people will just get fed up," conceded Mr Noble.

"The point is, we've done the difficult bit: we've got the car built. It's sitting there in our technical centre in Bristol and it's not so far from running."

Rocket question

On the plus side, Bloodhound's engineers now have more time to straighten out the rocket system and settle on a race configuration.

They have the option of initially running the car with a monopropellant rocket.

In this set-up, no fuel grain (synthetic rubber) is used. The oxidiser (hydrogen peroxide) is merely pumped across a catalyst to decompose and produce thrust.

It is simpler and should get Bloodhound to 800mph. It is also easier to prepare the car for the second of two runs (averaged together) that must be completed inside an hour to claim any new record.

But the team knows that if it is to achieve its ultimate goal of 1,000mph, the full hybrid system - solid fuel grain burnt in the presence of the liquid oxidiser - will be required.

The engineers will explore the options in the coming months with rocket partner Nammo of Norway.

"It's attractive to go with the monopropellant for year one, but eventually we will have to run with a cluster of three hybrid rockets," said Mark Chapman, Bloodhound's chief engineer.

"We have something of a luxury now to be able to debate the issue."

Schools backing

The plan now - assuming the money comes in - is to do some low-speed running on a UK runway later this year, before shipping out to South Africa in April/May of 2017.

In the meantime, the project's education programme continues.

The science behind Bloodhound is now being used in STEM (Science, Engineering, Technology and Maths) activities in 7,500 schools in the UK.

The programme is about to team up with the BBC's Micro:Bit codable computer. When this device is released in the next few weeks, children will be able to use it to investigate the behaviour of mini rocket cars.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published24 September 2015

- Published23 September 2015

- Published10 June 2015

- Published12 June 2015