Bacteria 'see' like tiny eyeballs

- Published

The idea first dawned when researchers looked down a microscope at bacteria lit from the side

Biologists say they have solved the riddle of how a tiny bacterium senses light and moves towards it: the entire organism acts like an eyeball.

In a single-celled pond slime, they observed how incoming rays are bent by the bug's spherical surface and focused in a spot on the far side of the cell.

By shuffling along in the opposite direction to that bright spot, the microbe then moves towards the light.

Other scientists were surprised and impressed by this "elegant" discovery.

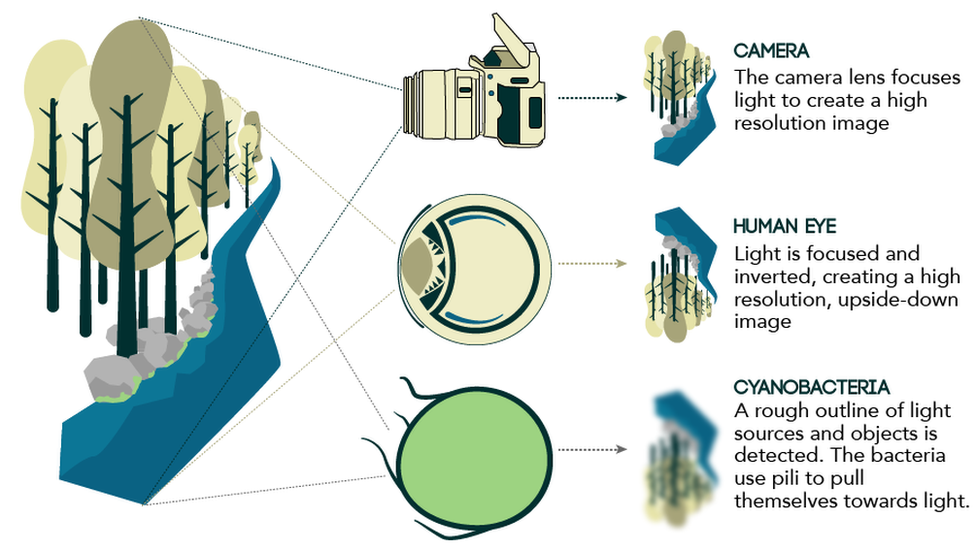

Despite being just three micrometres (0.003mm) in diameter, the bacteria in the study use the same physical principles as the eye of a camera or a human.

This makes them "probably the world's smallest and oldest example" of such a lens, the researchers write in the journal eLife, external.

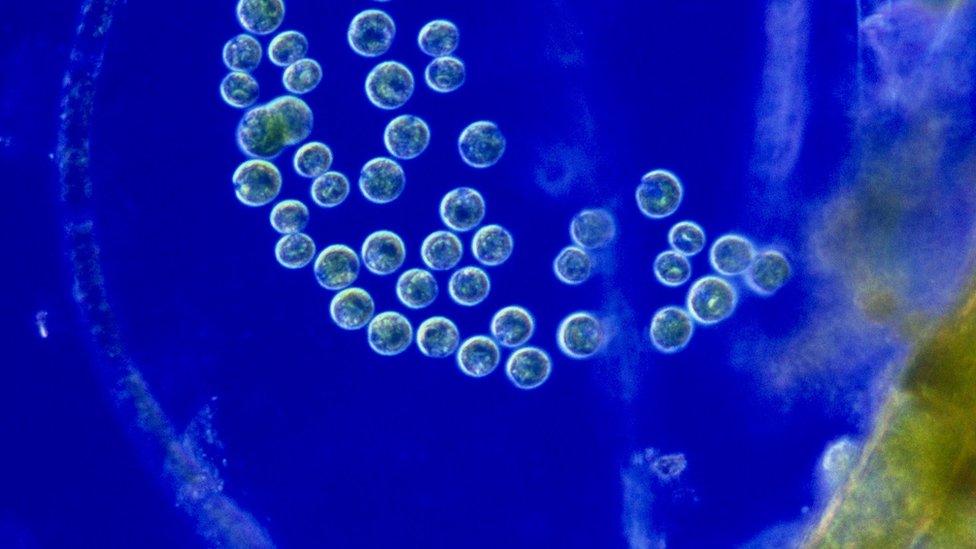

Cyanobacteria, including the Synechocystis species used in the study, are an ancient and abundant lifeform. They live in water and get their energy from photosynthesis - which explains their enthusiasm for bright light.

Bug eyes

"It has a way of detecting where the light is; we know that because of the direction that it moves. But we were puzzled about this because the cells are very, very small," said study co-author Conrad Mullineaux, from Queen Mary University of London.

Cyanobacteria are found in huge numbers in bodies of water and can form a slimy film

He told the BBC it was a chance observation through a microscope that put his team on the right track.

"We noticed it accidentally, because we had cells on a surface and we were shining light from one side, in order to watch the movement towards the light.

"We suddenly saw these focused bright spots and we thought, 'bloody hell!'. Immediately, it was pretty obvious what was going on."

After more than three centuries of scientists eyeballing bugs under microscopes, Prof Mullineaux said it was remarkable that nobody had picked up on this before.

"It seemed really, really obvious afterwards."

To confirm and describe this single-cell "vision", he worked with colleagues in the UK, Germany and Portugal on a series of experiments.

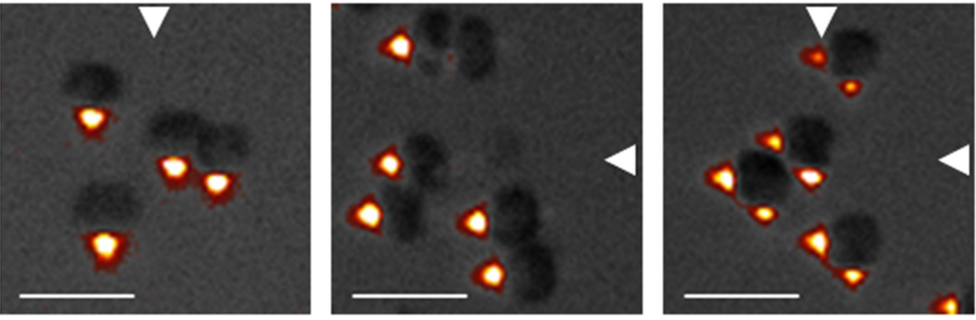

The bacteria focus light on the opposite side from where it arrives (white lines are 0.005mm long)

As well as studying the bacteria's focusing ability with different types of microscope, they used a laser beam to probe exactly how such focused light affected the bugs' behaviour.

With the laser beam trained steadily on the centre of a dish, the team shone a bigger, separate light on the Synechocystis cells from one side.

This drew the little critters across the surface in the usual way, pulling themselves towards the light with tiny tentacles. The usual bright "image" of the light was visible, focused on their trailing side.

But the moment any of the bugs strayed into the laser beam, there was an abrupt about-face.

"When they hit it, they bounced off it," Prof Mullineaux said. "As soon as the laser was hitting one side of the cell, the cells moved away. They switched direction."

Watch the microbes turn back when the laser shines on their forward side (time-lapse footage; numbers shown are minutes and seconds)

In other words, bright light focused on one side of the bacterium definitely does drive it to run the other way - which under normal circumstances takes it towards the source of the light.

In fact, because some amount of light is hitting the cell from all around, the team says that each microbe will have a "360-degree image" of its surroundings focused on the inside of its cell membrane.

Ancient mechanism

That image is very fuzzy - with a resolution of about 21 degrees, compared to the 0.02-degree precision of our eyes - but it is enough for photoreceptor molecules, embedded in the cell membrane, to guide the bug's movement.

For example, when the researchers shone two separate lights at the cells, they saw two focused bright spots and the bacteria appeared to integrate the information, heading off in an intermediate direction.

The team says that its findings probably apply to many species of small bacteria, but more work will be needed to figure out whether - and how - the system works in bugs that are not spherical, such as rod-shaped cyanobacteria.

The image focused by the bacteria is upside down, like in the human eye, but much blurrier

Some bigger single-celled organisms, meanwhile, are already known to use clumps of photoreceptors called "eyespots", along with other cellular components, to determine light direction.

The light-tracking power of Synechocystis is arguably much more remarkable, because it is incredibly small and incredibly simple - and previously unexplained.

Gaspar Jekely is a group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, Germany, and an expert on "phototaxis" - the process by which simple organisms move towards (or away from) light.

Commenting on the research, he told BBC News: "This was a mechanism that was missing. We didn't know it and it's a very elegant demonstration - and surprising.

"Cyanobacteria are 2.7 billion years old, so it's much older than any animal eye. Presumably, this mechanism has existed for a very long time."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published16 August 2010

- Published23 August 2010

- Published28 May 2015