MyShake quake app invites public testing

- Published

For its release, MyShake is available for Android devices; an iOS version will likely come with time

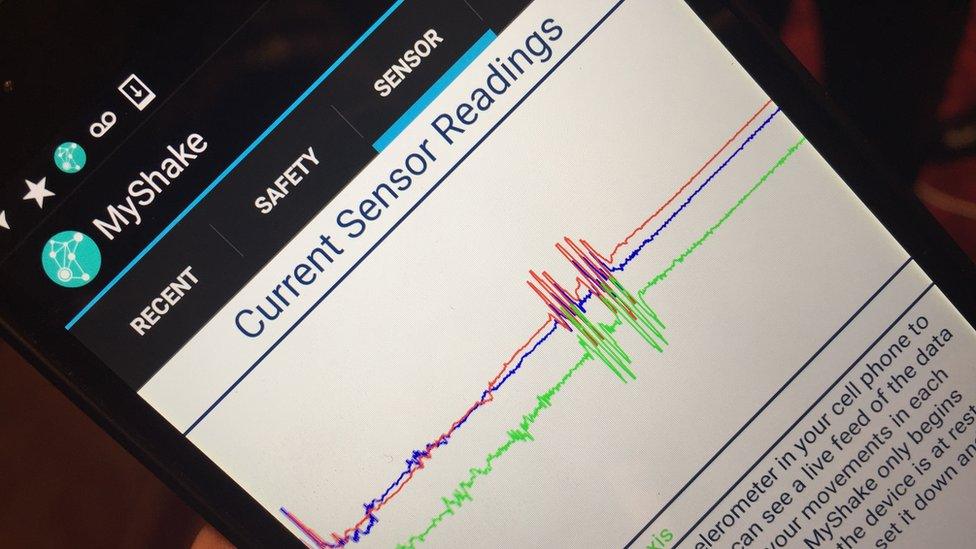

A new app that turns a smartphone into a mobile seismometer is being rolled out by California scientists.

Known as MyShake, external, it can sense an earthquake even when the cell device is being carried in a pocket or a bag.

The researchers want users to download the app, in the first instance, to help test and improve its capabilities.

But ultimately the idea is that recruited phones will be part of a network that not only gathers data but also issues alerts.

Destructive ground motions take time to move out from the epicentre of a large tremor, meaning people at more distant locations could receive several seconds' vital warning on their phones.

"Just a few seconds' warning is all you need to 'drop, take cover and hold on'," said Prof Richard Allen from the UC Berkeley Seismological Laboratory.

"Based on what social scientists have told us about past earthquakes, if everyone got under a sturdy table, the estimate is that we could reduce the number of injuries in a quake by 50%," he told BBC News.

Prof Allen has a paper about MyShake in this week's Science Advances journal, external, but he has also been demonstrating it here in Washington DC at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, external.

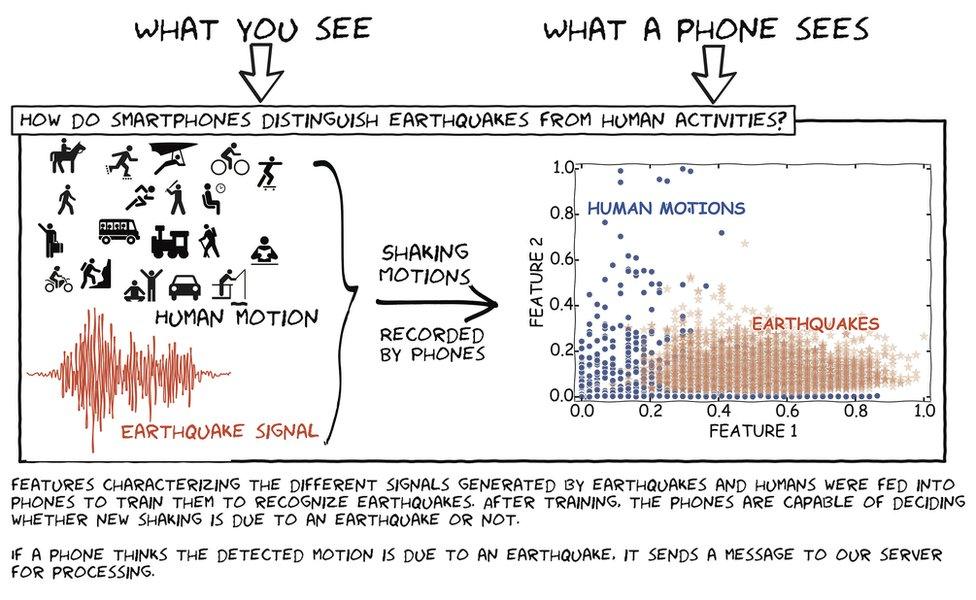

The app relies on a sophisticated algorithm to analyse all the different vibrations picked up by a phone's onboard accelerometer.

This algorithm has been "trained" to distinguish between everyday human motions and those specific to an earthquake.

The achieved sensitivity is for a Magnitude 5 event at a distance of 10km (6.2 miles) from the epicentre.

In simulations, the app detects a quake correctly in 93% of cases.

All this is done in the background - much like health apps that monitor the fitness activity of the phone user.

Once triggered, MyShake sends a message to a central server over the mobile network. The hub then calculates the location and size of the quake.

Napa Quake: Downtown San Francisco got eight seconds' warning of impending shaking

False positives are filtered out because the server is connected to existing seismic and GPS monitoring stations, and - if the public take up MyShake - thousands of other phones.

"We took the data from our traditional network gathered during the 2014 La Habra earthquake near Los Angeles, and downgraded its quality to something similar to what might be recorded on your smartphone, and then we applied the MyShake algorithm blindly to that data," Prof Allen explained.

"The system triggered rapidly and accurately, and that's really given us the confidence to now take MyShake out to the public for its big, real test."

For this release, MyShake is available for Android devices; an iOS version is very likely to come in the future. And to be clear, enrolled phones will not be receiving alerts of earthquakes - not yet.

Richard Allen: "In the future we can use this to provide early warning to people"

Prof Allen is a leading figure behind ShakeAlert, the earthquake early warning system, external now in development for California.

Only a few such systems exist in the world.

They work on the principle of being able to detect the faster-moving but not-so-damaging P-waves in a seismic event ahead of its S-waves, which cause most destruction.

California has several hundred state-of-the art seismic stations in the ShakeAlert system, and during the 2014 South Napa earthquake an eight-second warning of shaking was delivered to trial participants in downtown San Francisco. This included the city's metro system, BART, which wants to be able to slow its trains ahead of the biggest tremors.

The phones enrolled to MyShake would eventually get such warnings as well (see this dramatisation, external).

"The MyShake approach can contribute to and enhance earthquake monitoring in those parts of the world that have traditional seismic networks, like California. But perhaps even more importantly, because we can do a lot of this 'in the cloud', MyShake could help provide earthquake early warning in locations that have no traditional seismic network - places such as Nepal or India where we get very damaging earthquakes."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published11 December 2013

- Published5 December 2012