Gravitational waves: Numbers don't do them justice

- Published

Albert Einstein: His genius is made clear yet again

"It's astonishing; it really is." Jim Hough can't stop repeating the phrase.

The veteran gravitational wave hunter from Glasgow University has come to the National Press Club in Washington DC to witness the announcement of the first direct detection of ripples in the fabric of space-time caused by the merger of two "intermediate-sized" black holes.

The numbers look bald on paper, but it's when you try to imagine the scenario being described in those numbers that you rock backwards.

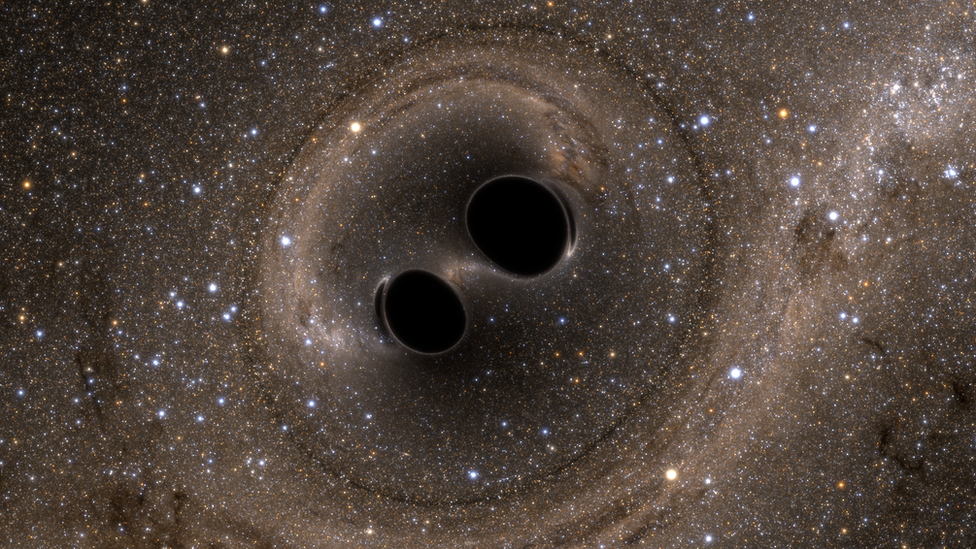

Imagine two monster black holes spinning down on each other in space. One has a mass which is about 35 times that of our Sun, the other roughly 30. At the moment just before they coalesce, they're turning around each other several tens of times a second. And then, their event horizons merge and they become one - like two soap bubbles in a bath.

David Reitze, executive director of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatories (LIGO), described it thus: "Take something about 150km in diameter, and pack 30 times the mass of the Sun into that, and then accelerate it to half the speed of light. Now, take another thing that's 30 times the mass of the Sun, and accelerate that to half the speed of light. And then collide [the two objects] together. That's what we saw here. It's mind boggling."

This simulation shows how the merging black holes warped space - watch the seconds tick down (video: SXS/Ligo)

In that moment of union, the holes radiate pure energy in the form of gravitational waves, and lose mass equivalent to three times that of our Sun. Energy equals mass times the speed of light, squared. Everyone knows the equation; this is it in action.

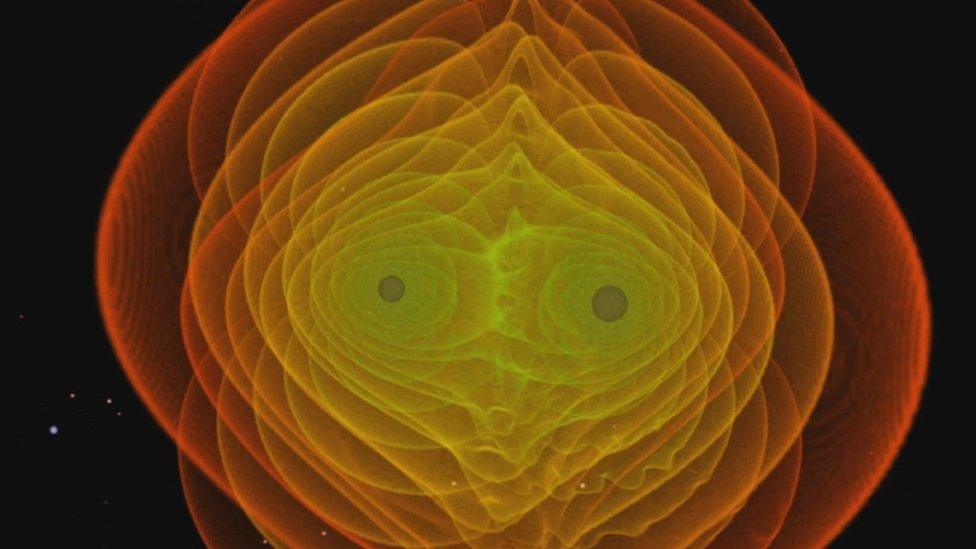

That tremendous release of energy, and the warping of space-time that results, is why the LIGO laboratories have been able to sense it, even though this staggering event occurred about 1.3 billion light-years from Earth.

A thousand researchers from 80 institutions in 15 countries are celebrating this moment. The excitement this week, building up to the announcement in the US capital, has been palpable. It's easy to see why.

Jim Hough, still astonished, speaking after the press conference

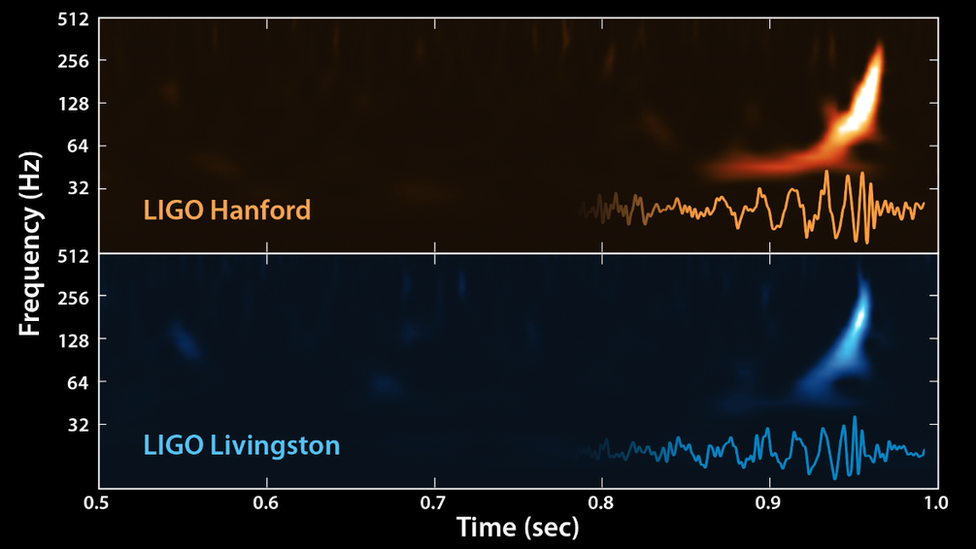

The detection of the black hole merger was made at 09:50:45 GMT on 14 September.

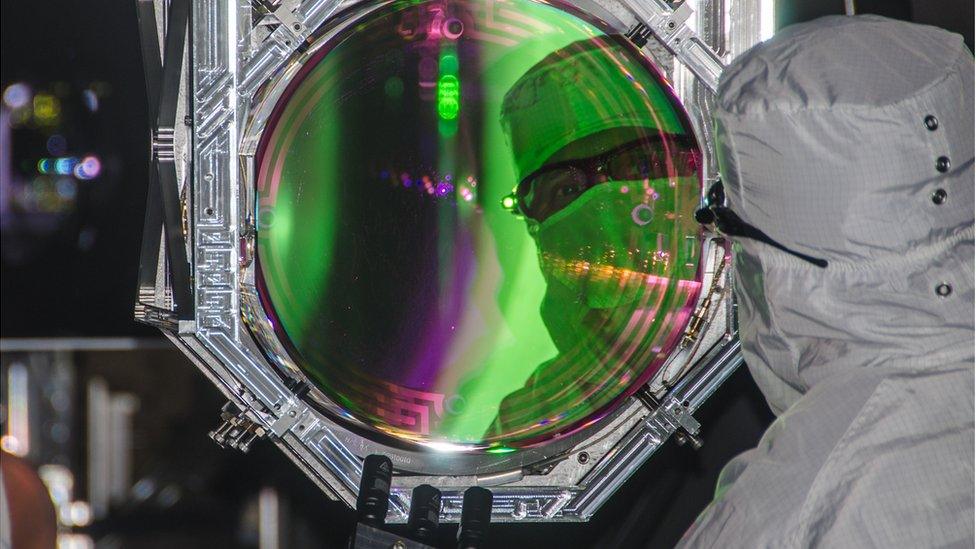

The laser interferometers operated by LIGO had only just come online after several years refurbishment to enhance their sensitivity. They weren't even in a formal science observation mode. The researchers were still going through commissioning checks when the detectors picked up the signal - a disturbance equivalent to someone nudging the ultra-quiet equipment by minute fractions of the width of a proton, the particle at the heart of all atoms.

The wave was detected almost simultaneously, in two labs 3,000km apart

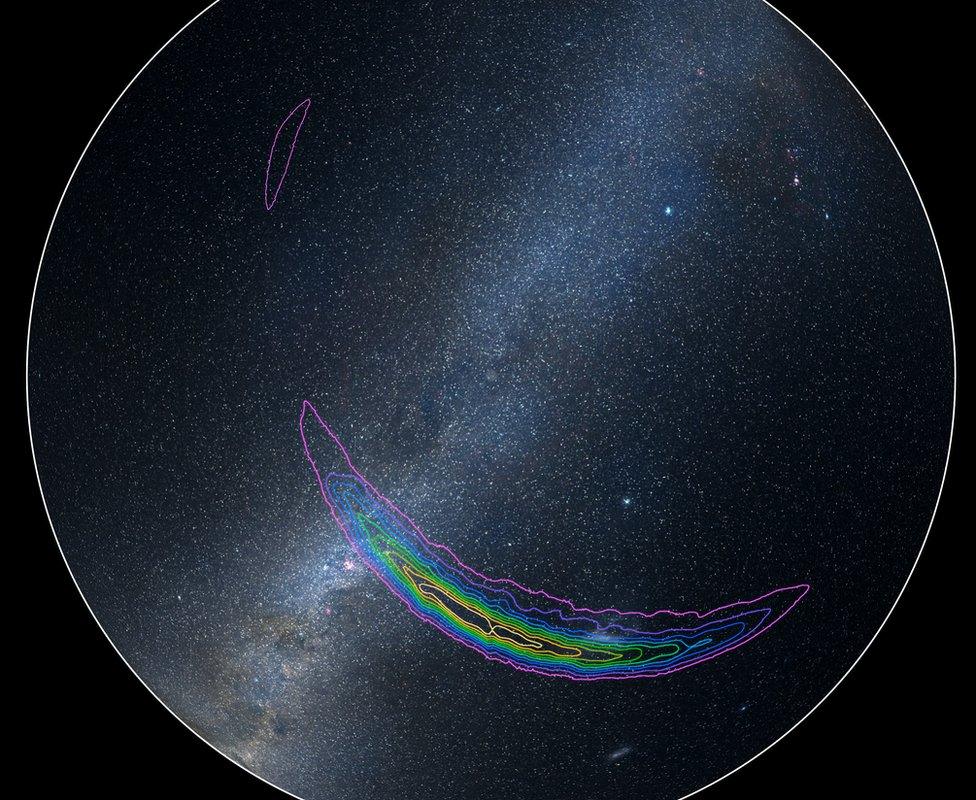

The LIGO lab at Livingston in Louisiana saw it first. The Hanford, Washington State, observatory 3,000km away sensed the bump seven milliseconds later. The distance to the event, the scientists are pretty confident about; the location, less so. Somewhere in the southern sky.

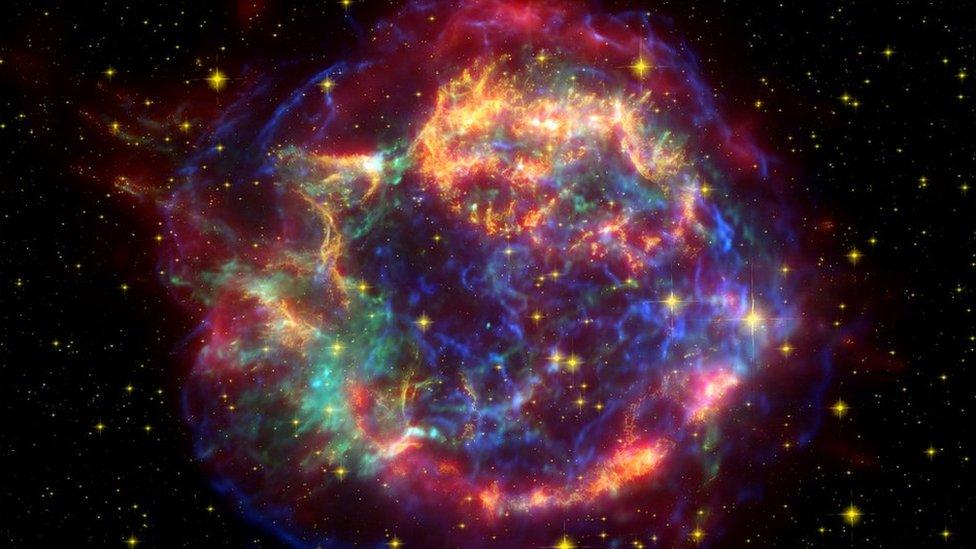

In some ways, it's difficult to know what to concentrate on. Is it the history-making detection of the waves themselves, or the detail of astrophysics they represent? This is the first direct observation of black holes, of black holes this size, and of them orbiting each other and merging.

And all the numbers are exquisitely in agreement with Einstein's equations. As predicted, the waves radiate at the speed of light - meaning the graviton, the putative particle that mediates gravitation, is massless (to the level that it's possible to tell).

"Although Einstein's equations are famously complicated, they are the simplest equations he could have come up with, given all the constraints he had to satisfy," commented Bernie Schutz from Cardiff University.

"It is remarkable that nature didn't add in even more complexity. But the equations are what they are, and they're beautiful."

Prof David Reitze: "Ladies and gentlemen, we have detected gravitational waves"

There will of course need to be further detections. The scientists think they may also have seen an event, much smaller, some weeks later, but this will need further assessment.

Looking to the summer, the LIGO labs will be running again after a period of downtime. When this happens, they'll be joined by a third observatory called Virgo, built near Pisa in Italy. Others are coming, too, in Japan and in India.

With all these "ears on the cosmos", it should be easier to identify where precisely in the sky the detected events are occurring.

And the European Space Agency is developing a gravitational wave observatory to put in orbit far from Earth. It will launch in the 2030s.

Currently, it's not the grand mission that everybody had hoped for, because the US space agency got in a muddle over its funding some years back and dropped the project. The scale of the mission was therefore redrawn. Many now hope that this historic breakthrough will prompt Nasa to come back in.

With just two "ears" to pinpoint it, the black hole merger can only be approximately located in the sky

"The compromise that was made, to build it in Europe so that the Americans didn't have to contribute, because they weren't going to, was not the best thing to do for the science; not for the size and the risk of doing that space mission," observed MIT's Rai Weiss.

"Consequently, many of us are trying to get the collaboration re-established."

It is really only by going into space and measuring gravitational waves from even bigger events, away from the noisy surface of the Earth, that researchers expect to see small chinks start to emerge in those glorious equations of Einstein.

Who gets the prize?

It is inevitable on these occasions that talk turns to Nobel Prizes. No-one is in any doubt that Thursday's announcement deserves one; the debate, as ever, is over who should receive it. Obvious candidates include the American Kip Thorne, the Scotsman Ron Drever and the German-born Rai Weiss himself. They are regarded as the fathers of LIGO, having proposed the concept back in the 1980s.

Advanced LIGO is arguably the most sensitive instrument ever built

But for Jim Hough, who started working on gravitational waves as a postgrad in the late 1970s, it would be appropriate if some of the glory went to the broad collaboration of researchers who made LIGO what it is. One thousand and four authors are listed on the breakthrough paper in Physical Review Letters, external.

"The Nobel committee should have given a prize to the Large Hadron Collider itself for the detection of the Higgs boson. All those experimentalists worked so hard to do it, and they should have been rewarded for it," he told me.

"But it's quite likely we'll see the same thing happening with gravitational waves, which would be a great pity in my view."

A big day for Rai Weiss and Kip Thorne

- Published11 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016