Climate stirring change beneath the waves

- Published

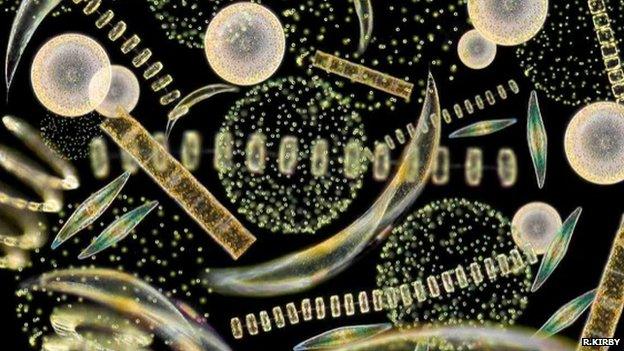

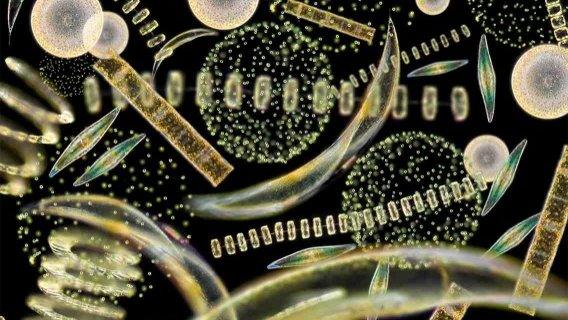

The role phytoplankton plays in life on Earth is often overlooked, says Dr Richard Kirby

Human-induced climate change is triggering changes beneath the waves that could have a long-term effect on marine food webs, a study suggests.

An assessment of phytoplankton in the North Atlantic found the microscopic organisms' pole-ward shift was faster than previously reported.

It observed that the ocean's tiny plant community was "poised for marked shift and shuffle".

The findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external.

"Marine phytoplankton are crucial in marine food webs and global biogeochemical cycles and they are incredibly diverse but we don't really have a sense of what all the different organisms do when you modify climate, or even through natural climate variability," explained co-author Andrew Barton, a researcher at Princeton University, working at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

He told BBC News: "This study attempted to get a handle on how all these different kinds of organisms may respond to anthropogenic climate change over the coming century."

Often mistaken for pollution, foam found on beaches is the decaying remains of vast colonies of phytoplankton commonly known as foam algae

The team studied 87 different species of microscopic marine plants found in the North Atlantic, looking at the organisms' mean historical range (1951-2000) and future (2051-2100) ocean conditions.

"The main results of the study were that we found that when the climate changes it was not just the temperature that was changing and impacting phytoplankton but it was also all the ocean circulation and the conditions in the ocean surface, such as nutrients and light, that have an ecological impact," Dr Barton observed.

"Generally, the whole physical environment is altered; in some cases, quite substantially."

The study found that the phytoplankton may move north-eastwards, he added: "That change is projected to be faster on a median level than than has been seen from looking at historical data for marine species."

He explained the findings differed from previous studies because it provided data on how different species were affected and moved.

"Some species do appear to not move at all. Some may move much further than others," Dr Barton said. "This study gives you a sense that there is quite a broad range of possible responses. If the species used to live here, where might it move?

"To my knowledge, most previous studies on marine phytoplankton have not answered those kinds of questions.

Finding out what will be the impacts of this shift in distribution of the phytoplankton will be the next steps, he said.

Decaying phytoplankton emits a gas called dimethyl sulphide (sulfide), which is responsible for the characteristic "smell of the sea" and plays a role in cloud formation

Globally, the tiny marine plants account for an estimated 50% of the planet's photosynthesis - the process of converting sunlight into fuel for organisms.

This involves absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which is then converted into sugars that the plant uses to grow.

It is this biochemical process that plays a key role in the global carbon cycle.

Other studies have reported a decline in the abundance of phytoplankton in the world's oceans.

In 2010, Canadian researchers published a paper in Nature suggesting that the tiny plants had recorded a global decline of 40% over the previous 50 years.

In response to these findings, marine biologist Richard Kirby set up the Secchi Disk Project, a citizen science study that allowed seafarers to submit their recordings of plankton abundance and increase the volume of data available to scientists monitoring the health of the oceans' plankton.

Commenting on the findings by Dr Barton and colleagues, Dr Kirby - who was not involved in the study - told BBC News: "The study adds to a growing body of evidence already describing large-scale, climate-induced changes in the distribution, abundance and seasonality of the plankton around the globe.

"The plankton are the seas' life-support system and any changes in where they occur will not only affect the distributions and abundance of other life in the sea upon which we depend, but will also influence the ecology of our entire planet with consequences for us all."

Dr Barton said his team's study was based on information gathered by the Continuous Plankton Recorder survey, run by the Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science, based in Plymouth, UK.

He said: "Without that sort of sustained monitoring programme, you really cannot do this kind of science. It is tremendously important and a huge resource for the scientific community."

- Published10 March 2014

- Published22 May 2015

- Published12 January 2016