Hubble sets 'new cosmic distance record'

- Published

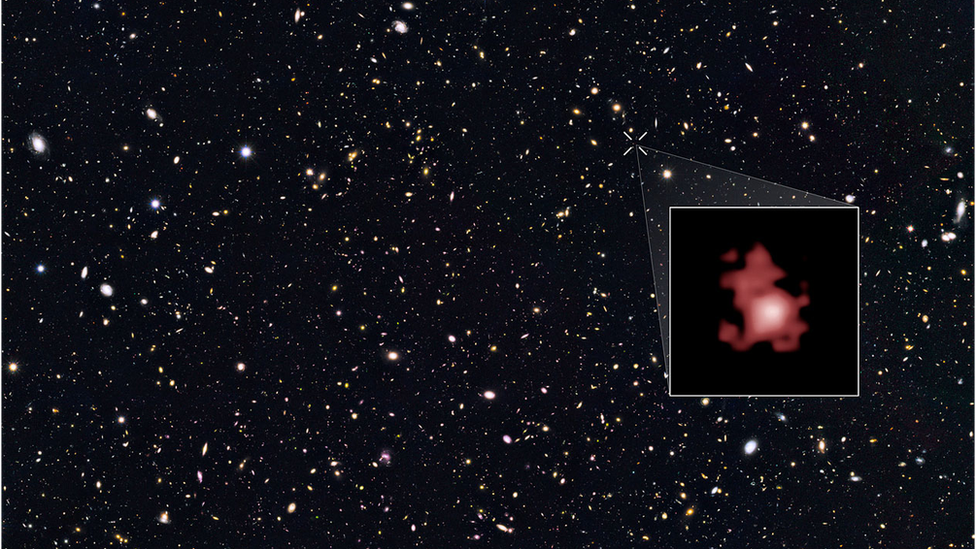

The galaxy GN-z11, pulled out in the inset, is seen only 400 million years after the Big Bang

The Hubble Space Telescope has spied the most distant galaxy yet.

It is so far away that the light from this extremely faint collection of stars, catalogued as GN-z11, has taken some 13.4 billion years to reach us.

Or to put that another way - Hubble sees the galaxy as it was just 400 million years after the Big Bang.

Astronomers say they are confident about the measurement because they have been able to tease apart and analyse the object's light.

Such spectroscopic assessments are difficult to perform on the most far-flung sources, but if it can be done it produces the most reliable distance estimates.

The details of the discovery will appear shortly in an edition of the Astrophysical Journal, external.

"This really represents the pinnacle of Hubble's exploration of galaxies across cosmic history," said Yale University, US, astronomer Pascal Oesch, the lead author on the study.

"Hubble has proven once again, even after almost 26 years in space, just how special it is.

"When the telescope was launched we were investigating galaxies a little over half-way back in cosmic history. Now, we're going 97% of the way back. It really is a tremendous achievement," he told BBC News.

Nonetheless, scientists believe they are now at the very limits of what the veteran observatory can achieve technically, and it will most probably fall to Hubble's successor to look even deeper into space.

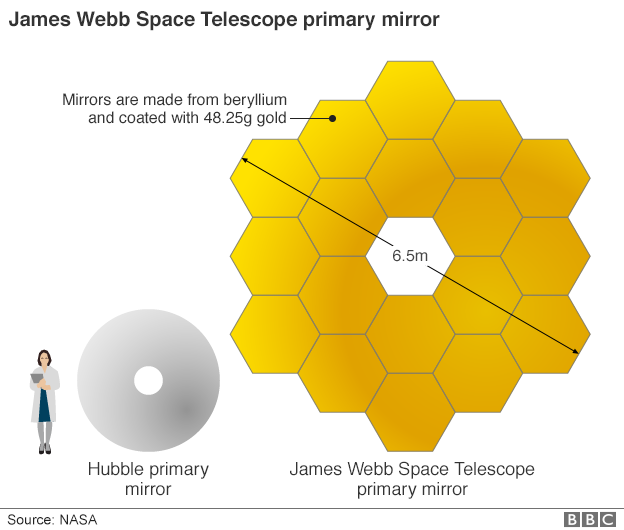

This is the James Webb Space Telescope, external, currently under construction and scheduled to launch in 2018.

One key difference between Hubble and JWST will be the size of their primary mirrors

Its instruments will be tuned to the infrared - to a specific region of the electromagnetic spectrum where the light from the very first stars to shine in the Universe should still be detectable.

They are probably another 200 million light-years beyond even GN-z11.

Scientists are keen to probe these founding stars and the conditions in which they were born.

They were likely hot giants that grew out of the cold, neutral gas that pervaded the cosmos back then.

These behemoths would have burnt brilliant but brief lives, producing the very first heavy elements.

They would also have "fried" the neutral gas around them - ripping electrons off atoms - to produce the diffuse plasmas we still detect between nearby stars today.

Dr Oesch and colleagues say GN-z11 is one-25th the size of the Milky Way with just 1% of our galaxy's mass in stars.

"The surprising thing is how bright it is (for what it represents), and it's growing really fast, producing stars at a much faster rate," said the Yale astronomer.

"So, it's challenging some of our models, but it's showing galaxy build-up was well under way early on in the Universe, and it's a great preview for James Webb, which will be pushing even deeper to see the progenitors of this galaxy."

Space Shuttle Discovery carried the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit on 24 April, 1990

GN-z11's identification was made with Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3, which was installed during the very last astronaut servicing mission, in 2009.

When astronomers discuss distance in the cosmos, they use the term "redshift". This is a measure that describes the way light coming from far-off galaxies is "stretched" by the expansion of the Universe.

The higher the redshift number assigned to an object, the more distant it is and the earlier it is being viewed in cosmic history.

Before this Hubble observation, the galaxy measured spectroscopically to have the greatest separation from Earth was given a redshift of 8.68 (13.2 billion years in the past).

GN-z11 has been assigned a redshift of 11.1, putting it some 200 million years closer to the time of the Big Bang.

JWST will probably have to see back to when the Universe was only one or two percent of its current age - which corresponds to about 100 to 250 million years after the Big Bang. This covers redshifts between 15 and 30.

(Updated: 6/3/16) Another "deep redshift hunter", Prof Richard Ellis, currently with the European Southern Observatory, said full and final acceptance from the astronomical community of the distance ascribed to GN-z11 would likely come only with follow-up observations.

"All previous spectra of [greater than redshift 7] galaxies have been secured using large ground-based telescopes using traditional 'slit' spectrographs that mask out most of the overlapping sky signal," he told BBC News.

"The Hubble grism is a very low-resolution instrument and, in deep fields, all the spectra overlap and it requires considerable effort to disentangle the signals."

While GN-z11 was a possible candidate for a very high-redshift galaxy, he added, "the ultimate proof can only come from a higher resolution spectrum".

The James Webb Space Telescope is due for launch in 2018

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published26 January 2016

- Published31 July 2015

- Published23 April 2015

- Published17 February 2015

- Published6 January 2015