Tests find trees tolerant to olive tree killer pathogen

- Published

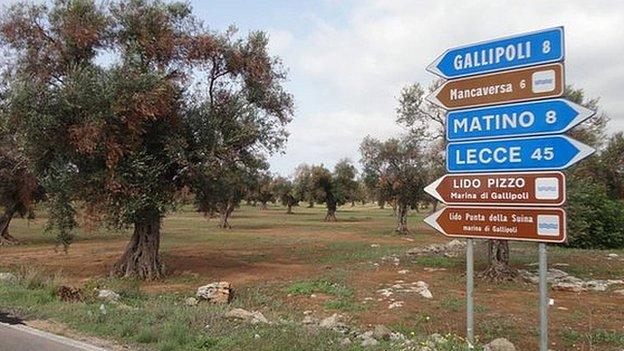

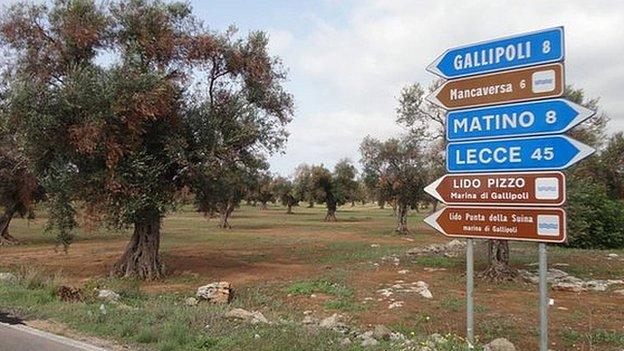

The invasive pathogen has affected thousands of hectares of olive plantations in Puglia, southern Italy

Tests suggests some varieties of olive trees appear to be resistant to an invasive pathogen posing a serious risk to Europe's olive industry.

The findings came to light during a study into the host range of the bacteria, external, which reached Europe in 2013.

The findings offer hope of limiting the impact of Xylella fastidiosa that experts described as one of the "most dangerous plant pathogens worldwide".

If it is not controlled, it could decimate the EU olive oil industry.

The study, carried out by Italian researchers and funded by the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA), began in 2014 and consisted of two main types of experiment: artificial inoculation (via needle) and inoculation via infected vectors (insects) collected from the field.

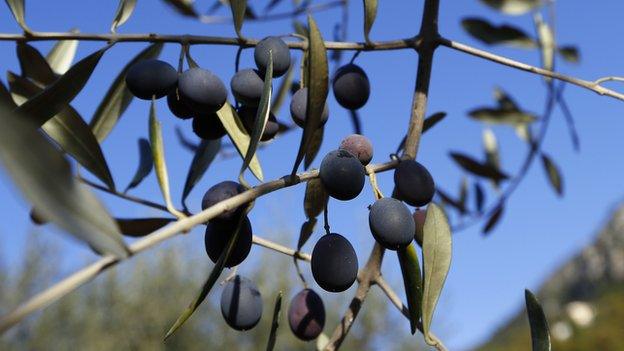

The tests were carried out on a variety of species, including a range of olive, grape, stone-fruit (almond and cherry) and oak varieties.

Growing understanding

"The first results are coming from the artificial inoculation because the field experiments began in the summer so it is only six months old, therefore only part of the results are available," Giuseppe Stancanelli, head of the EFSA's Plant and Animal Health Unit, told BBC News.

"The key results are that, 12-14 months after artificial inoculation on different olive varieties, the team found that young plants typically grown in the region displayed symptoms of the dieback.

"The research team also found evidence of the bacterium moving through the tree - towards it root system as well as towards the branches."

But he added: "What has also been shown is that some varieties have shown some tolerance. They grow in infected orchards but do not show strong symptoms, as seen in more susceptible varieties.

"They are still infected by the inoculation but this infection is much slower so it takes longer for the infection to spread, and the concentration of the bacterium in the plant is much lower.

"This shows the potential for different responses (to the pathogen) in different varieties."

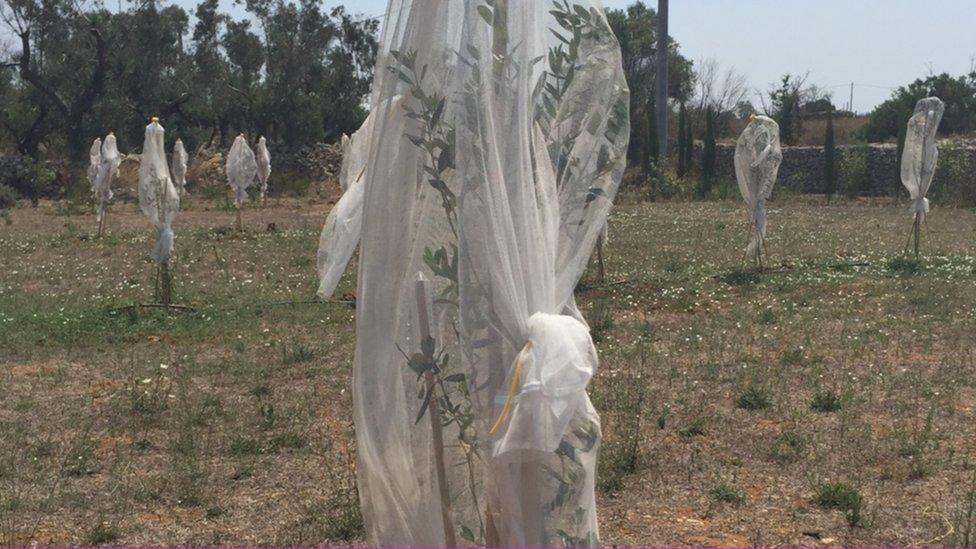

Researchers hope the study will help shape a strategy to contain the spread of the potentially devastating disease

Dr Stancanelli added that these results were important in terms of providing information for tree breeders.

However, it was too early to say whether or not the olive yields from the varieties that have displayed tolerance to the infection are nonetheless reduced or adversely affected, he observed.

The EFSA Panel on Plant Health produced a report in January warning that the disease was known to affect other commercially important crops, including citrus, grapevines and stone-fruit.

However, the results from the latest experiments offered a glimmer of hope.

"Olives seemed to be the main host of this strain while citrus and grapes did not show infection, either in the field or by artificial inoculation," Dr Stancanelli said.

He added that the infection did not spread through the citrus and grape plants that were artificially inoculated, and the bacterium was not found beyond the point it was introduced to the plant by injection.

But he added that more research was needed on stone-fruit species.

"The tests on the artificially inoculated varieties of stone-fruit need to be repeated because there is a mechanism in the plants that makes artificial inoculation difficult," Dr Stancanelli explained.

"Another uncertainty we had was about (holm) oak. Quercus ilex is a typical Mediterranean oak that grows in the landscape and is natural vegetation.

"At the beginning of the outbreak in 2014, some symptoms were found on oaks and the tests were positive but this was never confirmed so this was probably a 'false positive'.

"The artificial inoculation test appears to have shown that the holm oak is resistant (to the disease)."

Reducing uncertainty

The Xylella fastidiosa bacterium invades the vessels that a plant uses to transport water and nutrients, causing it to display symptoms such as scorching and wilting of its foliage, eventually followed by the death of the plant.

Since it was first detected in olive trees in Puglia, southern Italy, in October 2013, it has been recorded in a number of other locations, including southern France. To date, it has yet to be recorded in Spain, the world's largest olive oil producer.

Experts warn that should the disease, which has numerous hosts and vectors, spread more widely then it has the potential to devastate the EU olive harvest.

Globally, the EU is the largest producer and consumer of olive oil. According to the European Commission, the 28-nation bloc produces 73% and consumes 66% of the the world's olive oil.

Recent reports suggest that the X. fastidiosa outbreak has led to a 20% increase in olive oil prices during 2015.

The study sought to identify what species were susceptible to the invasive pathogen

In November 2015, the European Commission announced it was providing seven million euros (£5m) from the EU Horizon 2020 programme, external to fund research into the pathogen.

One of the areas of the Horizon 2020-funded research will be on plant selection to strengthen tolerance and resistance to the disease.

Dr Stancanelli explained that the experiments established in this study would continue as part of the EU-funded Ponte programme, external.

"The experimental field realized within the pilot project will serve as unique source of plant material for future project actions aiming at investigating the host-pathogen interactions," he said.

"Investigations will be extended to an additional panel of 20 cultivars which will be planted in... April in the same plot."

The disease plagued citrus farmers in North and South America for decades. It remained confined on these continents until the mid-1990s when it was recorded on pear trees in Taiwan.

According to the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO), which co-ordinates plant protection efforts in the region, the pathogen had been detected prior to 2013 by member nations on imported coffee plants from South America. However, these plants were controlled and the bacterium did not make it into the wider environment.

The arrival of the disease in Italy and its spread to southern France led to the European Commission issuing EU-wide control measures, external in 2015.

Earlier this year, when a cold-tolerant subspecies of the bacterium was identified in the southern France outbreaks, UK government plant health officials published information for horticulture professionals, external, especially those importing plants. They were advised of their obligations - such as obtaining the necessary plant passports - and given details of the visible symptoms to look out for on potentially infected plants.

Follow Mark on Twitter, external

- Published13 November 2015

- Published9 January 2015

- Published24 March 2015

- Published2 September 2015

- Published30 July 2015