Gravitational wave mission passes 'sanity check'

- Published

Scientists have in mind their preferred type of space observatory - but it is expensive

A European Space Agency effort to try to detect gravitational waves in space is not only technically feasible but compelling, a new report finds.

A panel of experts was asked to perform a "sanity check" on the endeavour, which is likely to cost well in excess of one billion euros.

The Gravitational Observatory Advisory Team, external (Goat) says it sees no showstoppers.

It even suggests Esa try to accelerate the project from its current proposed launch date in 2034 to 2029.

Whether that is possible is largely a question of funding. Space missions launch on a schedule that is determined by a programme's budget.

"But after submitting our report, Esa came back to us and asked what we thought might be technically possible, putting aside the money," explained Goat chairman, Dr Michael Perryman.

"We are in the process of finalising a note on that, which will suggest the third quarter of 2029. So, 13 years from now," he told BBC News.

The agency has stated its intention to build a mission that investigates the "gravitational Universe", and is set to issue a call to the scientific community to submit a detailed proposal.

Ripples in the fabric of space-time

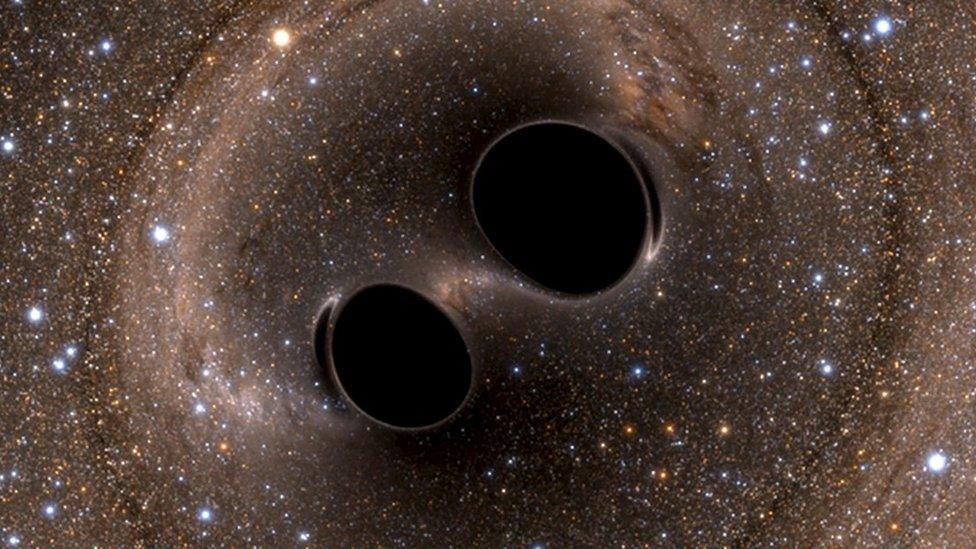

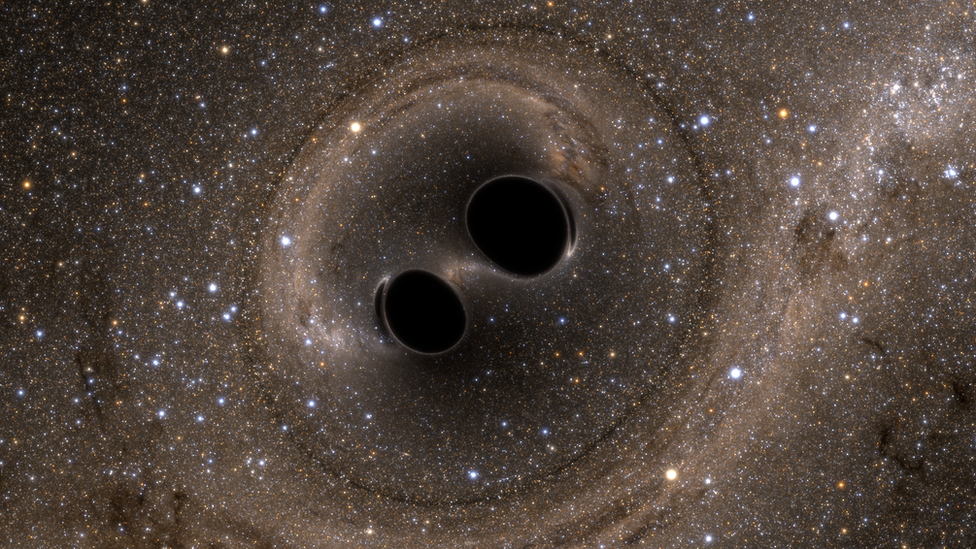

Artwork: Advanced Ligo detected coalescing black holes more than a billion light-years from Earth

Gravitational waves are a prediction of the Theory of General Relativity

Their existence had been inferred by science but only recently directly detected

They are ripples in the fabric of space and time produced by violent events

Accelerating masses will produce waves that propagate at the speed of light

Detectable sources ought to include merging black holes and neutron stars

Ligo fires lasers into long, L-shaped tunnels; the waves disturb the light

Detecting the waves opens up the Universe to completely new investigations

Gravitational waves - ripples in space-time - have become the big topic of conversation since their first detection last year by the ground-based Advanced Ligo facilities in the US.

Using a technique known as laser interferometry, the labs sensed the fantastically small disturbance at Earth generated by the merger of two black holes more than a billion light-years away.

The discovery opens up a completely new way to do astronomy, allowing scientists to probe previously impenetrable regions of the cosmos and to test some of the fundamental ideas behind general relativity - Einstein's theory of gravity.

The Goat says the stunning detection by Ligo is a game-changer: "In a single step, gravitational wave astronomy has been placed on a secure observational footing, opening the panorama to the next robust steps in a space-based gravitational wave observatory."

That was not the case when the panel started its work. Then, there were many people who thought a detection might be beyond our measurement capability.

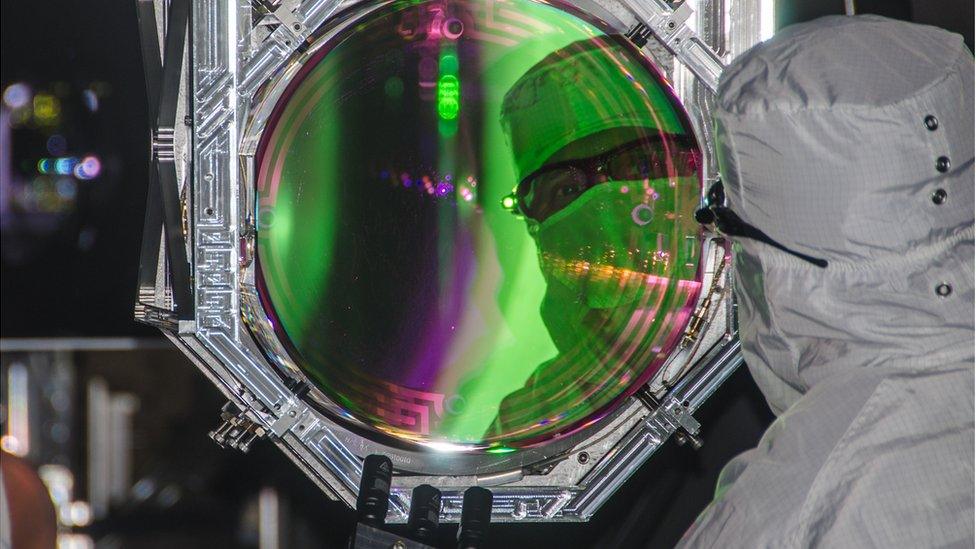

The Goat believes that any space-borne observatory Esa might pursue should proceed using the same technical approach as Advanced Ligo - laser interferometry.

Advanced Ligo employs laser interferometers - the technology suggested also for a space mission

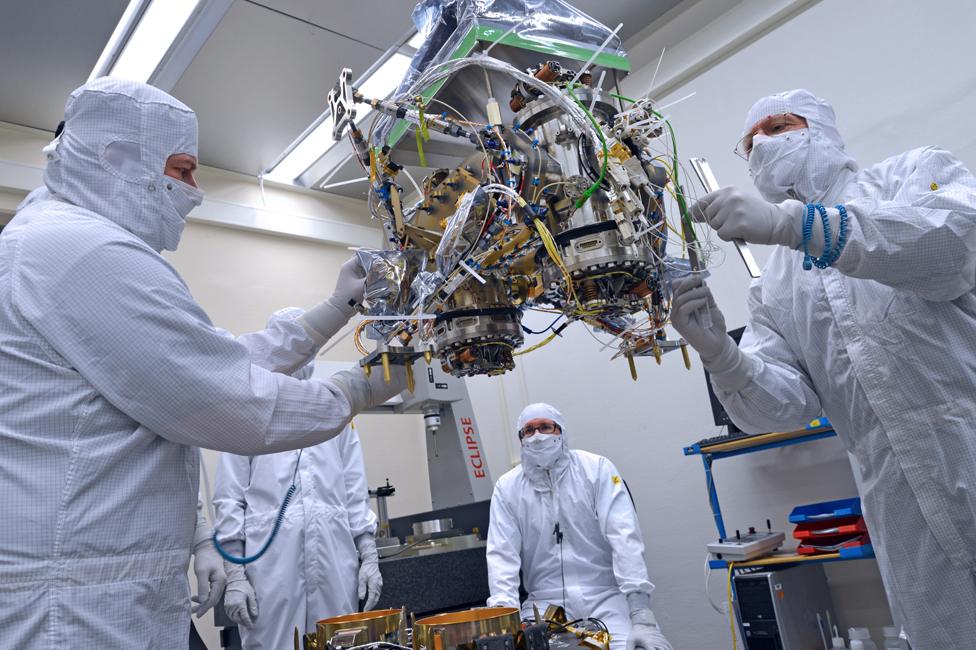

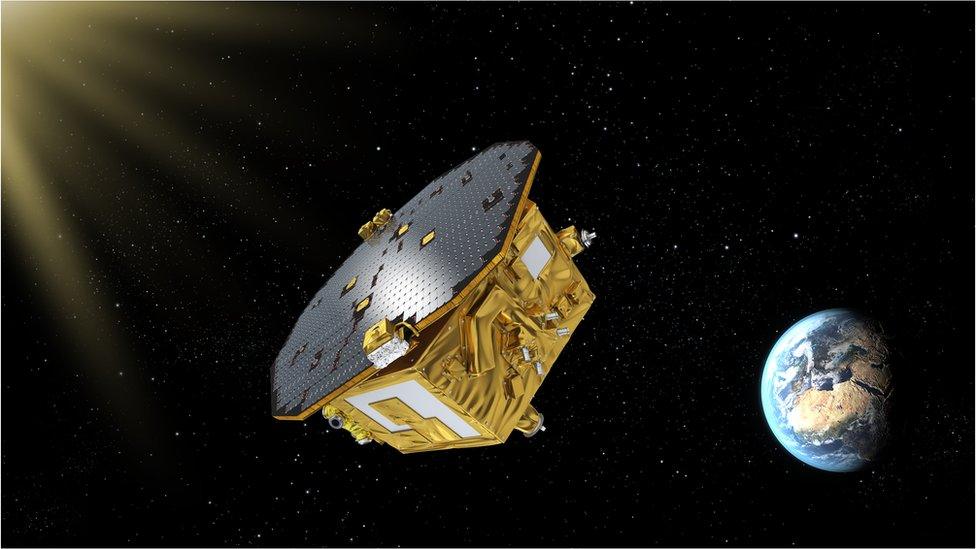

The agency is currently doing experiments in orbit that will prove some of the equipment needed on a future gravitational wave observatory. But the Goat also identifies critical additional developments that must now be prioritised to take the laser approach into space.

That said, there is also encouraging support in the report for an alternative detection concept called atom interferometry. This is too immature at the moment to be a contender, the Goat says, but it could benefit from a technology demonstration mission in the near future.

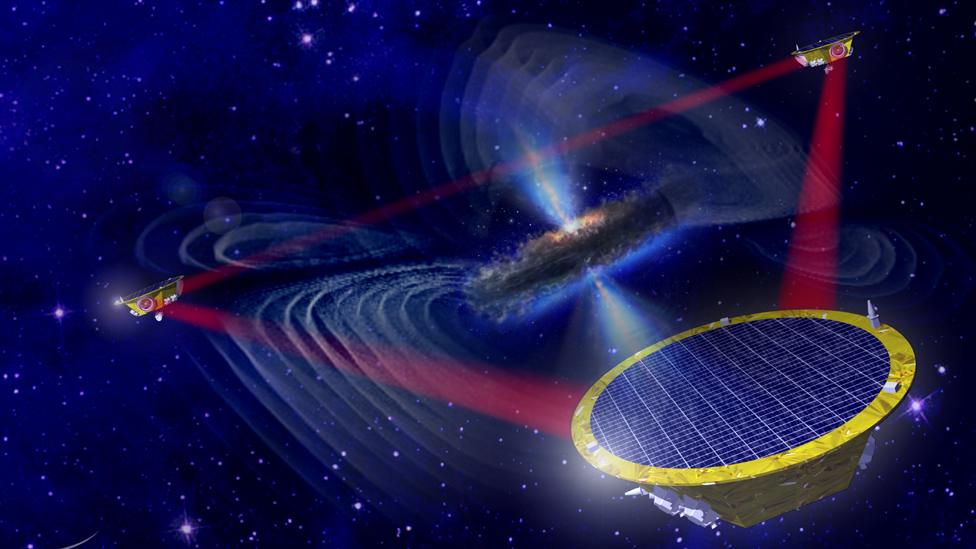

Since the 1980s, scientists have been working on a system to detect gravitational waves from orbit called Lisa - the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna.

It would fly a network of satellites separated by a few million kilometres.

Lasers fired between these spacecraft would sense ripples in space-time generated by much more massive objects than the black holes seen by Ligo. Lisa's targets would be the monster black holes, millions of times the mass of our Sun, that coalesce when galaxies collide, for example.

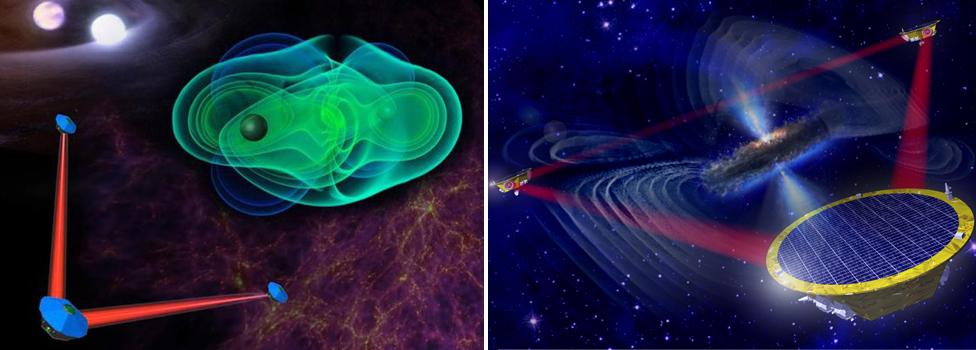

Future Lisa: How many lasers can you fly?

The available budget will determine the architecture of an operational Lisa mission

Esa is set to fly a mission dedicated to gravitational astronomy in the 2030s

The current Lisa design proposes a two-arm laser interferometer (left)

But scientists would prefer to fly an architecture that has three arms (right)

The latter could more easily locate gravitational wave sources in the sky

Whether two or three arms are flown will depend on the available budget

At present, Esa rules only permit a maximum 20% involvement from Nasa

But it may require a bigger US participation to get the full architecture

Lisa was previously proposed as a joint venture between Europe and the US.

When the Americans then ran into funding difficulties and pulled out, scientists on the European side "de-scoped" the mission to try to make it fit within the financial envelope available at the time. Many commentators thought this revised design compromised the science to an unacceptable degree.

Researchers on both sides of the Atlantic are now pushing hard to go back to the old arrangement.

This potentially represents something of a headache for Esa's hierarchy.

Following the American withdrawal, the European Space Agency instigated a "rule" that foreign contributions to its missions should in future represent no more than 20% of the overall cost.

The restriction was designed to ensure that no mission could be scuppered by a sudden change of heart from an international partner.

But this financial ceiling may have to be broken if the US is to come back onboard and participate in the type of space mission that gravitational wave scientists most want to see fly.

The Goat "suggests that such a mission will be more robust, and provide a greater science return per euro, if the US could consider a larger contribution, including a re-establishment of a meaningful collaboration."

The call to formally propose a new mission and its architecture should go out within the next 12 months.

"It is to be determined precisely when, but within the year," confirmed Dr Fabio Favata, head of Esa's Science Planning and Community Coordination Office.

"The call will ask the community to define a realistic mission in detail. In the meantime, we are already in discussions with our member states and Nasa about who could do what, at least in the study phase. The implementation phase would take more time, of course."

Esa is already developing some technologies, but the Goat says others must now be prioritised

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published1 March 2016

- Published4 September 2015

- Published12 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published28 November 2013