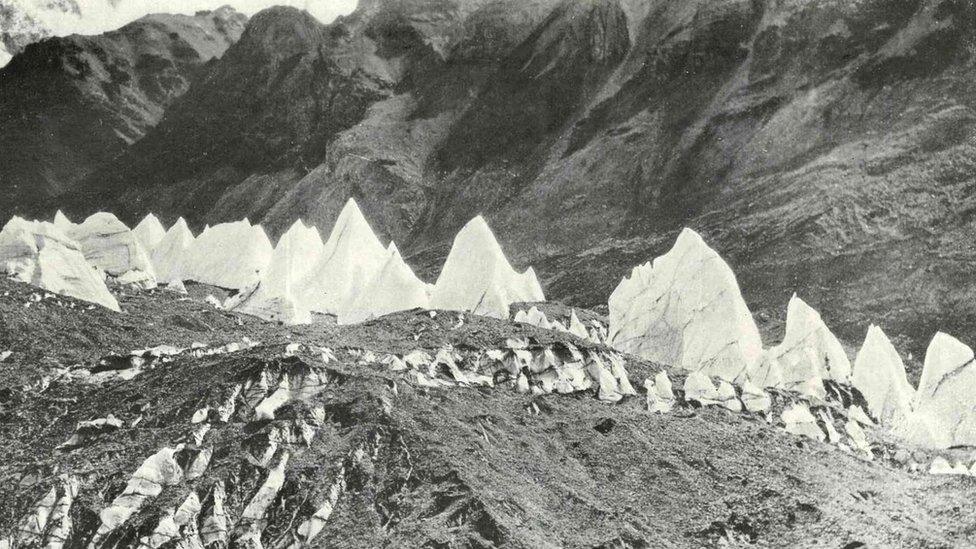

Glaciers with a flotilla of 'ice sails'

- Published

Like a flotilla of sail boats heading down the estuary

Rare and somewhat esoteric. These are the huge pyramids of ice that stand proud of the surface on some glaciers.

To date, the phenomenon has only really been seen around the Karakoram mountain region of Pakistan.

The Baltoro glacier, which begins life at the very summit of K2, has some particularly fine examples.

Up to 25m in height and with widths of up to 90m, their triangular shapes when viewed from a distance give the impression of a flotilla of sail boats.

Now, scientists are getting a handle on how these giant "ice sails" form and wither over time, and how the processes involved depend on the special conditions that exist in the Karakoram region.

Geoff Evatt: "Scientists are driven to find new, or unexplained, phenomena"

It all starts with the dirty surface at the head of a glacier.

Fragments of rock fall from the steep valley sides, darkening the top of the ice stream.

This makes it less reflective and able to absorb more solar radiation.

As a consequence, the glacier warms and begins to melt downwards; its whole surface drops - except where there are patches of clean ice.

These brilliant white areas, in contrast, continue to reflect the sun's rays. Their melt-rate is much slower and so they appear to rise as everything around them descends.

Thus, the sails are born, and they move down the valley with the progressing stream - like boats sailing down an estuary.

The sails can persist for decades, perhaps even more than a hundred years

But then, over the decades, the glacier accumulates yet more rock-fall, and this extra debris gradually begins to insulate the main body of ice.

For the great spires, on the other hand, the fortunes are reversed.

It is now their melt-rate that is dominant, and they continue to decay and die.

The big question for scientists, though, was why these sails were so prevalent in the Karakoram region, explained Dr Geoff Evatt from Manchester University, UK. His group has been modelling the problem.

"Firstly, you need the right geographic, topographic setting, where the glacier is long enough for an ice sail to form its shape and not, say, fall off an ice cliff," he told BBC News.

"But you also need a very dry atmosphere; the humidity level needs to be very low, which is why we don't really see these in the European Alps or Alaska where the atmosphere is a lot more moist."

Lindsey Nicholson: "Debris covered glaciers behave differently"

Places like Baltoro are hard to reach; some of the glaciers are up around 6,000m. So, while climbers have long walked past and admired the ice sails, there has been relatively little study done on them.

That is changing. Debris covered glaciers in general are becoming an increasing focus for research.

Not only do they look different compared with the pristine white flows we normally think of - they behave differently as well.

Debris covered glaciers do not simply retreat up valley when it is warmer and advance down valley when it is cooler or wetter. Rather, their terminus tends to be more static thanks to the protective insulating blanket.

This stagnant property actually makes it harder to discern a deposition history and so retrieve some sort of climate record from the glaciers. But understanding how they will react in a warmer world in paramount.

The person walking beside the sail gives a sense of their immense scale

Glaciers act like valves in the hydrological system: they regulate the flow of water to lower elevations. And for many people the continuation and constancy of this melt supply is critical.

"We want to be able to calculate better how these glaciers produce their meltwater," explained co-worker Dr Lindsey Nicholson from Innsbruck University, Austria.

"To do that, we need to explain better how energy is transferred from the atmosphere to the ice, through the debris cover.

"This cover is going to change the timing of the delivery of water to the hydrological system, both in the local environment but also ultimately in the run-off to the ocean.

"So it's important for us to know how these glaciers behave so that we can understand how - or indeed if - we should be accounting for the role of debris cover in global models of sea-level rise."

The ice sail research, which included contributions from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Germany, was featured at the recent European Geosciences Union, external General Assembly.

Look at the centre of the glacier in this Google Earth image to see the sails

The glaciers eventually dump their debris cargo, sometimes damming a lake of meltwater

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published17 December 2015

- Published26 December 2011