Chicxulub 'dinosaur' crater drill project declared a success

- Published

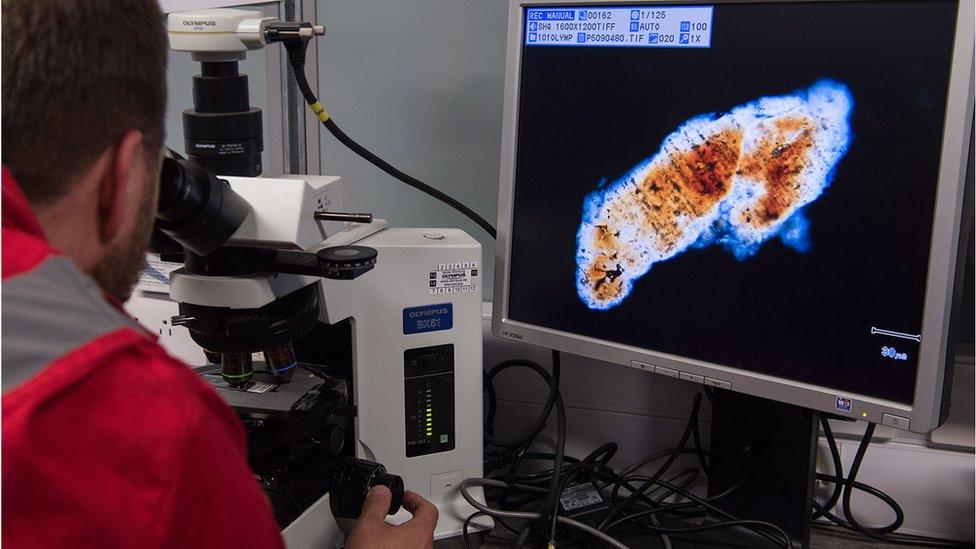

Impact breccia: Rock recovered from the peak ring of the Chicxulub Crater

The effort to drill into the Chicxulub Crater off the coast of Mexico has been declared an outstanding success.

A UK/US-led team has spent the past seven weeks coring into the deep bowl cut out of the Earth's surface 66 million years ago by the asteroid that hastened the end of the dinosaurs.

Rocks nearly 1,300m below the Gulf seafloor have been pulled up.

The samples are expected to reveal new insights on the scale of the impact and its environmental effects.

Dave Smith and Jo Morgan are delighted with the outcome of the drilling exercise

The operations manager on the project, Dave Smith, said drilling would likely end at midnight on Wednesday.

"The core recovery, we're all really chuffed about - the almost 100% core recovery and the quality of the cores we've been getting up.

"It's been a remarkable success. We've got deeper than I thought we might do," the British Geological Survey man said.

Co-lead scientists Jo Morgan (Imperial) and Sean Gulick (University of Texas) have exclusive access to the samples

The original target was to get down to 1,500m, cutting through a feature called the "peak ring" in the process.

This ring was created at the centre of the impact hole where the Earth rebounded after being hit by the city-sized space object.

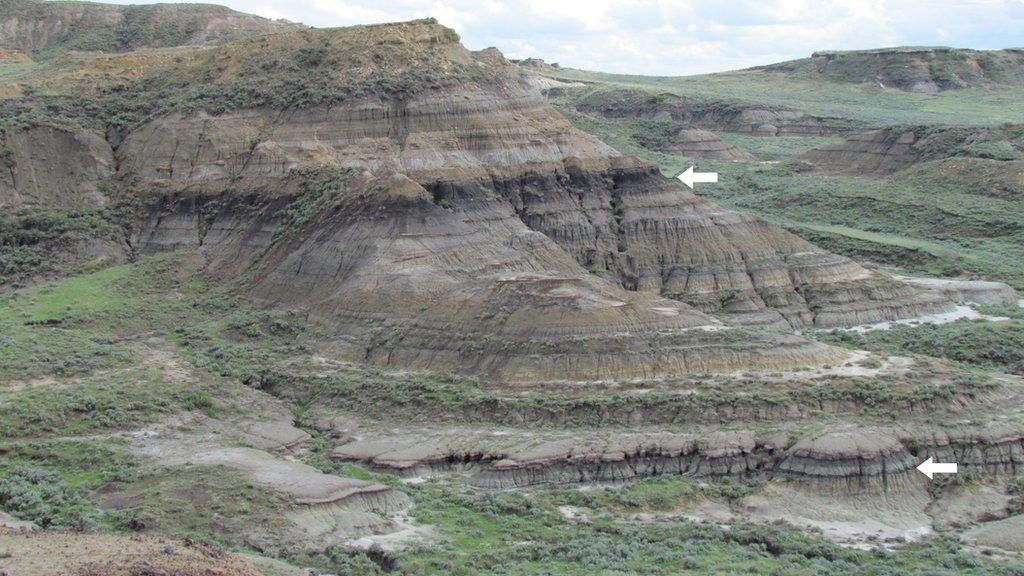

In earlier geophysical surveys that were able to sense below the seabed, the feature looked like an arcing chain of mountains.

Rocks from the ring have certainly been sampled. And even if the 1,500m mark was not reached, the team believes it has more than enough material now to answer its key science questions.

Some immediate investigations were done on the Myrtle, but the important work will take place in Bremen shortly

"It's been quite magical," said Imperial College London's Prof Joanna Morgan, who spoke via a satellite link from the Myrtle drill platform.

"Before I came out here, I remember getting quite nervous, quite anxious - what would happen? Would we be successful? But since I've been on the Myrtle, I've been quite calm because things have been happening, and we've been getting lovely cores."

The rock samples in their metal casings have been stacked in a refrigerated container.

They will be transported back to shore and sent first to an American lab for CT scanning, to examine their interior structure.

Then they will go to Bremen, Germany, where the 33 individuals on the science team will gather to subject the rocks to a battery of tests.

Job done: Jo Morgan first proposed a Chicxulub drill project almost 20 years ago

The space object that slammed into the planet at the end of the Cretaceous Period instantly dug out a hole 100km wide and 30km deep.

The debris hurled outwards would have darkened the sky and chilled the climate for months on end, driving many creatures to extinction, not just the dinosaurs.

But the precise details of how the event progressed can now be refined by examining the drill cores.

From the rocks, the research team should be able to tell better how the crater formed, the energy involved in its excavation, and the volume of material that was dispersed.

This will put new limits on the nature of the environmental changes that enveloped the globe.

Other intriguing questions will be also be addressed, such as how fast life was able to return to the sterilised impact zone.

There is even a suggestion that the hot fluids moving through the fractured rocks left by the impact may actually have embraced and fostered micro-organisms. The team now has the material to test this idea.

Chicxulub Crater - The impact that changed life on Earth

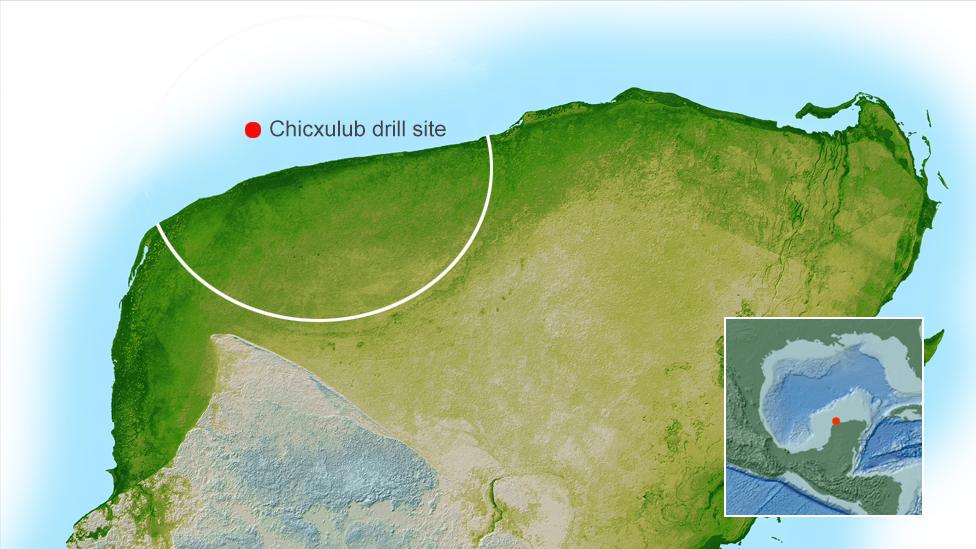

The outer rim (white arc) of the crater lies under the Yucatan Peninsula itself, but the inner peak ring is best accessed offshore

A 15km-wide object dug a hole in Earth's crust 100km across and 30km deep

This bowl then collapsed, leaving a crater 200km across and a few km deep

The crater's centre rebounded and collapsed again, producing an inner ring

Today, much of the crater is buried offshore, under 600m of sediments

On land, it is covered by limestone, but its rim is traced by an arc of sinkholes

Mexico's famous sinkholes (cenotes) have formed in weakened limestone overlying the crater

The scientists get a year's exclusive access to the material, after which others in the research community can take a look.

"Ultimately, the cores go to a facility in Texas where anybody can then sample them. Everything is archived. If someone has a new geochemistry measurement, they can go look at the core for a long, long time into the future," said Prof Morgan.

The science team has members from the US, Mexico, Japan, Australia, Canada, and China, as well as the UK and five other European countries.

The project was organised through the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD), external and the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), external.

The pictures on this page were taken by Max Alexander, external, who visited the Myrtle drill boat at the beginning of May.

Max works a lot with the UK Space Agency (UKSA) and arranged for British astronaut Tim Peake, external, currently on the International Space Station, to take the spectacular photograph of Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula at the very bottom of the page.

Max's images were taken for Asteroid Day (30 June), external - a campaign that aims to raise awareness of "asteroids, the impact hazard they may pose, and what we can do to protect our planet" from them.

The drillers have experienced very few problems and got deeper than many thought possible in the time available

Astronaut's view: The crater is buried partly offshore and partly onshore, under the Yucatan Peninsula

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published5 April 2016

- Published8 February 2013

- Published22 March 2013

- Published5 April 2011