Neanderthal stone ring structures found in French cave

- Published

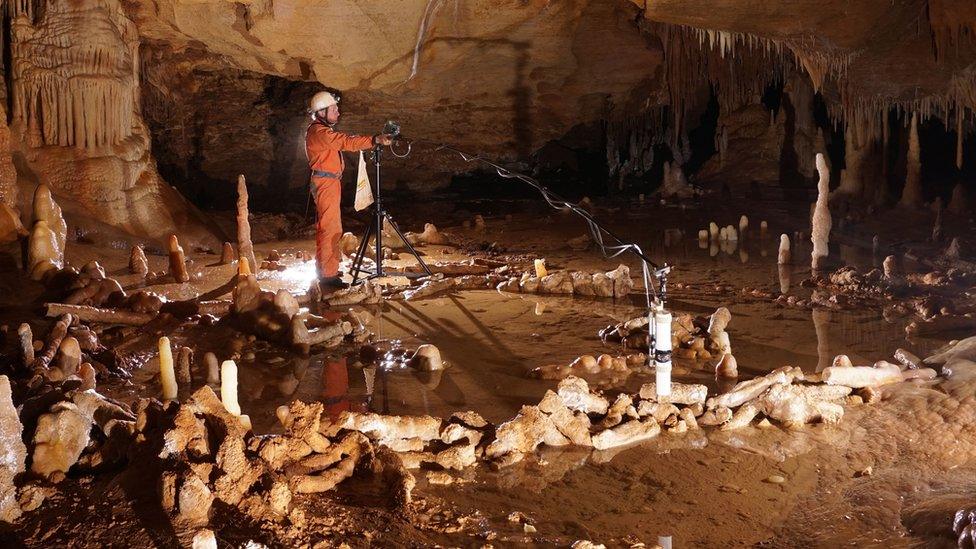

The structures were found deep inside the cave, so the builders would have needed fire to see

Researchers investigating a cave in France have identified mysterious stone rings that were probably built by Neanderthals.

The discovery provides yet more evidence that we may have underestimated the capabilities of our evolutionary cousins.

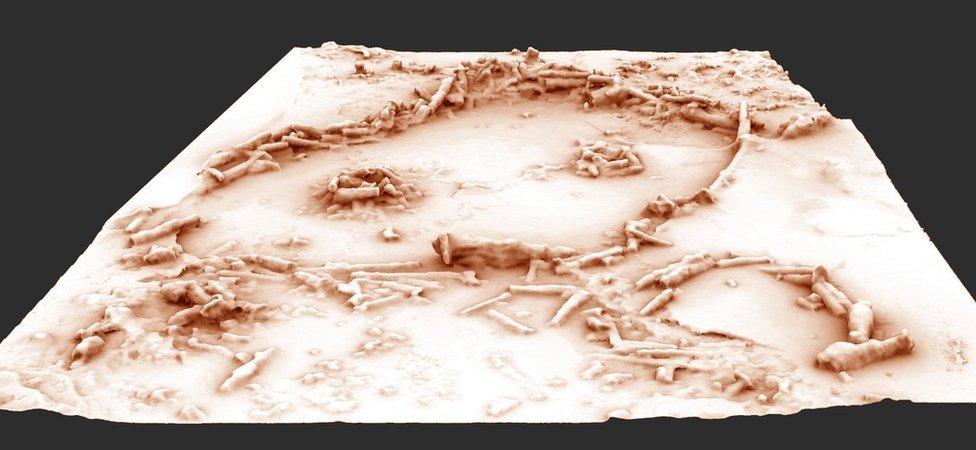

The structures were made from hundreds of stalagmites, the mineral deposits which rise from the floors of caves.

Dating techniques showed that they were broken off 175,000 years ago.

The findings are reported in the journal Nature.

The round structures were discovered in Bruniquel Cave in South-West France. The stalagmites had been chopped to similar lengths and laid out in two oval patterns up to 40cm (16in) high.

"Their presence at 336m from the entrance of the cave indicates that humans from this period had already mastered the underground environment, which can be considered a major step in human modernity," the researchers write in their study.

Co-author Jacques Jaubert, from the University of Bordeaux, said he had ruled out the possibility that these carefully constructed rings, which show traces of fire, could have come about by chance or have been assembled by animals such as the bears and wolves whose bones were found near the entrance of the cave.

The scientists made a 3D reconstruction of the manmade structures

"The origin of the structures is undeniably human. It really cannot be otherwise," he told The Associated Press news agency.

The Neanderthals who built them must have had a "project" to go so deep into a cave where there was no natural light, he explained.

They probably explored underground as a group and co-operated to build the rings, using fire to illuminate the cave, he said.

Prof Chris Stringer, of London's Natural History Museum, called the discovery "remarkable", adding: "At around 175,000 years, these must have been made by early Neanderthals, the only known human inhabitants of Europe at this time."

Conditions at the time the structures were built were particularly cold, and the recesses of the cave would probably have provided a temperate refuge.

Prof Stringer, who was not involved in the study, commented: "If there is still-buried debris from occupation, it would help us to determine whether this was a functional refuge or shelter, perhaps roofed using wood and skins, or something which had more symbolic or ritual significance.

"Some of the burning must surely be associated with lighting in such a dark location, but only further discoveries from this or other sites will show us how common were such deep cave occupations in the ancient past, and what their purpose might have been."