Olm eggs: First two Slovenian 'dragons' emerge

- Published

The first hatchling olm, or proteus, emerged on Monday

After a four-month wait, the eggs laid by a peculiar salamander in a Slovenian cave have started to hatch.

Ghostly pale and totally blind, olms - fondly known by locals as "baby dragons" - only reproduce every 5-10 years and are thought to live to 100.

This clutch of eggs started to appear in January in an aquarium in Postojna Cave, a tourist destination where the creatures have lived for millennia.

Observing baby olms develop and hatch is a rare opportunity for science.

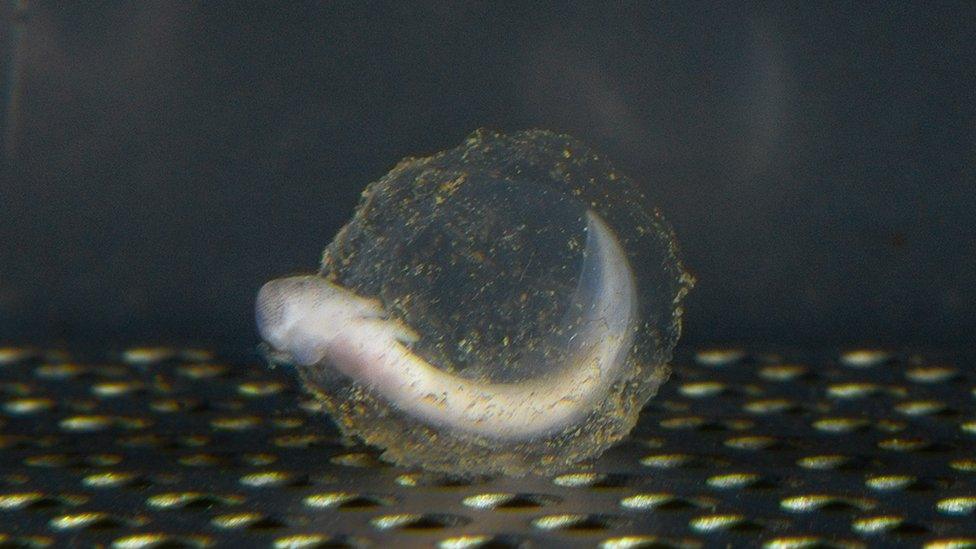

The first of 23 developed eggs hatched on 30 May; a second baby olm (pictured below) was slowly wriggling out of its egg on Wednesday night.

The second of the clutch to hatch is taking it rather slowly

"It is the end of one part of the story and the beginning of a whole new chapter: feeding and living without the egg," said Saso Weldt, who looks after and studies the olms at Postojna Cave, external.

He told BBC News nobody witnessed the first egg hatching, but the moment was captured thanks to an infrared camera.

"I was in the cave doing some other biological work. Since we have all the eggs on an IR camera, we saw that one was missing. Then you rewind and suddenly you realise, something has happened."

Mr Weldt and his colleagues hope to see a full count of 23 healthy hatchlings within a few weeks.

The staff at Postojna have been consulting amphibian experts to help them care for the fragile eggs, including a French team that has studied the olms in an underground mountain lab, external since the 1950s.

That laboratory is the only other place where these animals have ever been observed emerging from their eggs.

With their distinctive pale skin, these animals are adapted to their underground habitat

"In the cave, in nature, they hatch all the time - but nobody here has ever seen a hatchling younger than about two years," Mr Weldt said.

This clutch of eggs, which has captivated the Slovenian public, was laid by a single female over a period of several weeks.

"We did not do a paternity test, so we cannot know if it was a single father or not. But it was one mother," Mr Weldt said. "She's with our colony of proteus and she's doing well."

The eggs have been kept in a separate enclosure and watched very closely.

This microscope image, taken on 20 May, shows one of the embryos inside its egg

Originally there were 64, but only 23 embryos developed. The rest of the eggs were unfertilised and decayed, or were lost to fungal infections in the water.

"It's quite normal - the losses are expected," said Mr Weldt.

In fact, the baby dragons' odds would likely be much worse in the wild.

"In nature, out of 500 eggs let's say, two adults may arrive."

Native to the subterranean rivers of the Balkans, these bizarre and iconic animals acquired their nickname in centuries gone by, when floods occasionally washed their pallid, wriggling bodies into the open.

Dragons are legendary in this region - and the pink lizard-like beasts with their unique, frilly gills were taken to be babies of the species.

The olm has protruding gills and three toes on its front legs, but two toes on its hind legs

When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, he cited olms and their sightless, undeveloped eyes as an example of natural selection in action.

Darwin reportedly was offered some olm specimens but refused because he feared he would not be able to keep the sensitive little organisms alive.

Decades earlier, the famous scientist Humphry Davy visited the region and encountered the proteus in caves.

He was fascinated by the immature, tadpole-like appearance of the adults and discussed at length, external whether science would ever establish how these animals reproduce - or if they were, as it was rumoured, immortal.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published29 February 2016

- Published8 April 2015