Pluto's 'beating heart' explained

- Published

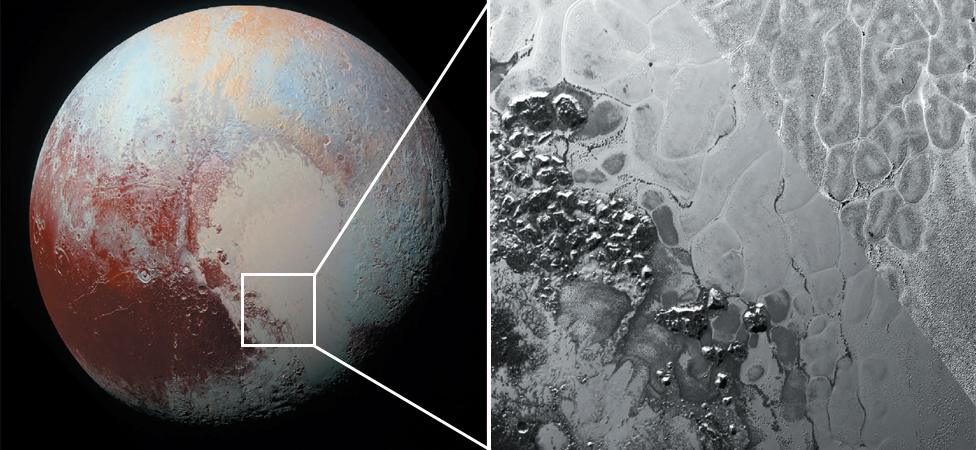

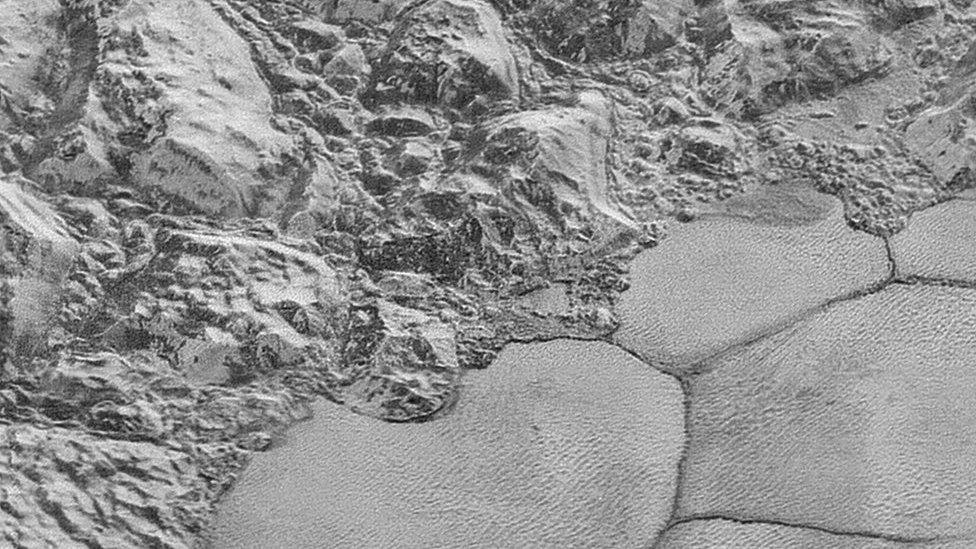

Sputnik Planum forms the "left ventricle" of Pluto's "heart"

The spectacular, flat landscape that dominates the left side of Pluto's icy "heart" can now be explained, say scientists.

Sputnik Planum is the most prominent feature on the diminutive world, covering 900,000 square km.

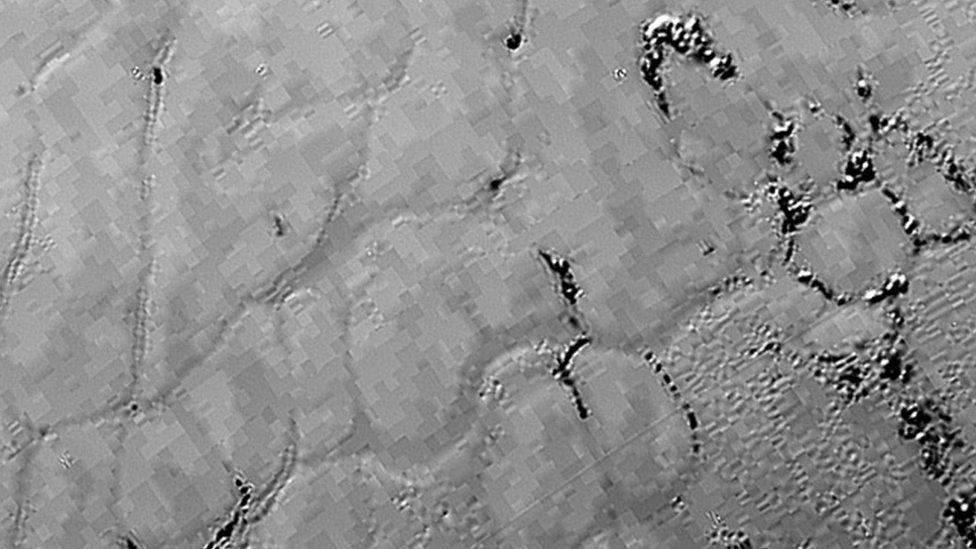

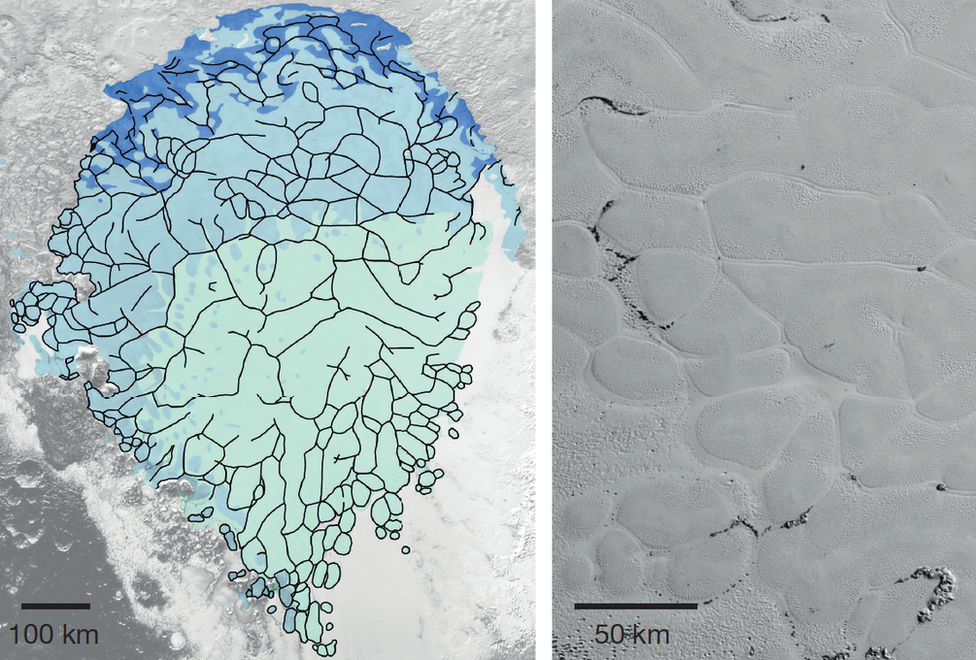

Broken into an array of polygons, it is devoid of any impact craters.

Reporting in the journal Nature, the researchers say that roiling cells of nitrogen ice remove any blemishes, maintaining a super-smooth appearance.

They argue that a competing idea, that the polygons are a consequence of cooling and contraction akin to giant "mud cracks", does not fit with the observations.

"It's a vigorously - from a geological point of view - churning layer of solid nitrogen, and it's [as if] the heart of Pluto is truly beating," said Prof Bill McKinnon, external from Washington University in St Louis, Missouri.

The assessment is based on the data acquired by the US space agency's New Horizons probe, which made the historic first flyby of Pluto last July.

Radioactive heart

Two separate teams have looked at the information from that encounter and have come to broadly the same conclusion - that only overturning ice, driven by the dwarf planet's internal heat, can produce the cellular terrain.

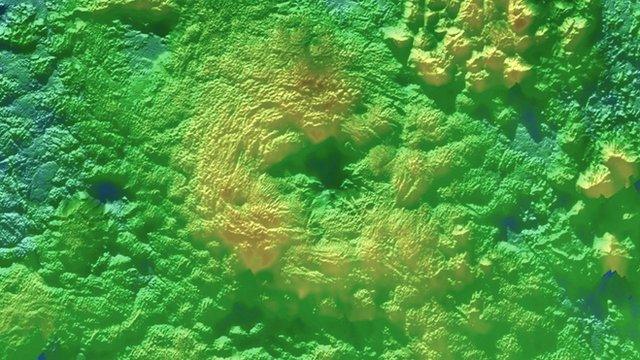

The polygons are typically about 10-40km across, tiling a deep basin that is surrounded by high mountains.

Each cell is domed, standing some 50m above its edges. Those edges then give way to troughs that can reach 100m in depth.

Bill McKinnon: "The plain is mostly solid nitrogen ice"

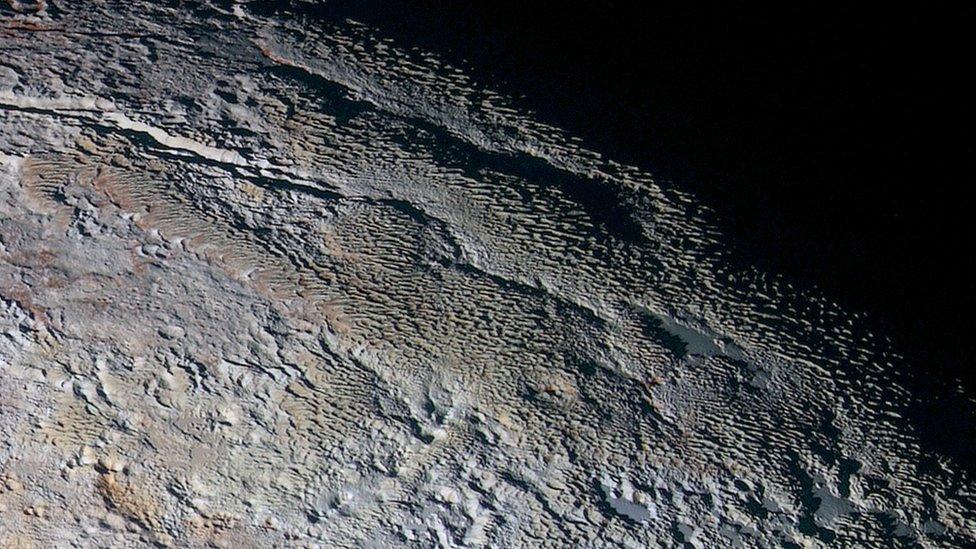

New Horizons found the planum ices to contain mostly nitrogen, with limited amounts of methane and carbon monoxide.

At the temperatures that persist on Pluto's surface (an extremely frigid -235C), this material is still capable of flowing.

Modelling work suggests just a few centimetres per year of horizontal movement in the tops of the domes would be sufficient to re-surface them in short order - significantly faster than the likely rate of impacts from bodies falling on to Pluto.

"From the calculated average velocity of convection, about 1.5cm per year, we compute the time needed for the ice surface to renew itself, and therefore the maximum age of the surface of Sputnik Planum, to be about one million years," report Alex Trowbridge, from Purdue University, Indiana, and colleagues in the second of the two Nature papers, external.

Convection requires energy, of course. And the scientists say this would come from radioactive elements incorporated into Pluto at its formation, and which should still be producing the necessary heat to promote the rise and fall of ice within the cells.

'Sluggish lid'

There are, however, scaling laws for convection that describe the relationship between the width and depth of convective cells. Taken at face value, these might imply the basin in which the polygons are sitting to be 10-20km deep.

This is somewhat deeper than expected for the underlying basin, but Bill McKinnon and colleagues invoke an idea they call "sluggish lid convection". This sees the dome surface move at a much slower pace than the deeper, warmer subsurface. If this operates at Pluto, the convection system could be much shallower; perhaps 3-6km deep, says Prof McKinnon.

"It all depends on the rheology - how nitrogen ice responds to pressure, temperature and other factors. The stuff at the top moves much more slowly because it's colder. It's 37 degrees kelvin (-236C). It's only modestly warmer down below but it's enough to make the nitrogen ice move," he told BBC News.

The polygons are typically about 10-40km across

Sputnik Planum was without doubt one of the standout discoveries of the New Horizons flyby.

It is the place where geologically recent activity on Pluto is most evident.

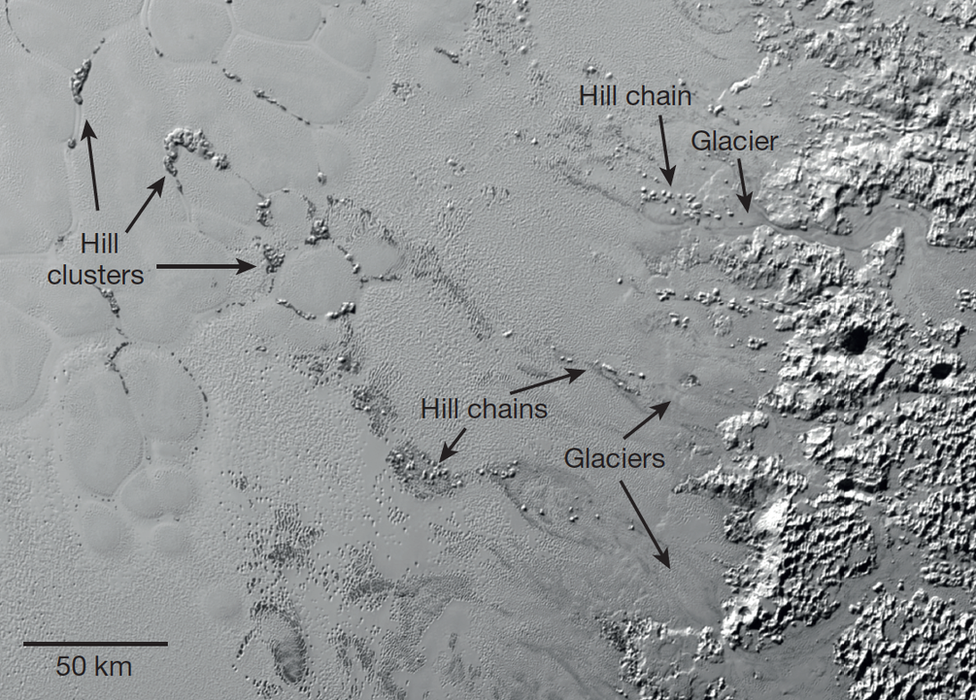

Glaciers of nitrogen ice are observed to move away from the water-ice mountains, into the plain.

Giant boulders are carried by some of these ice streams. And because water-ice floats on nitrogen ice, the mountain fragments tend to collect in the polygons' troughs, unable to sink with the downward flow of convection. This gives the appearance of chains of hills.

Although no impact craters are seen on Sputnik Planum, there are fields of kilometre-scale pits, particularly in its eastern and southern regions. These are sectors where there is no convection.

The stagnant ice here likely vaporises over time to produce the pits. It is all part of the process that cycles nitrogen between the plain, the atmosphere, the mountains, and back into the plain via the glaciers.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published4 December 2015

- Published9 November 2015

- Published25 September 2015

- Published17 July 2015