Ancient birds' wings preserved in amber

- Published

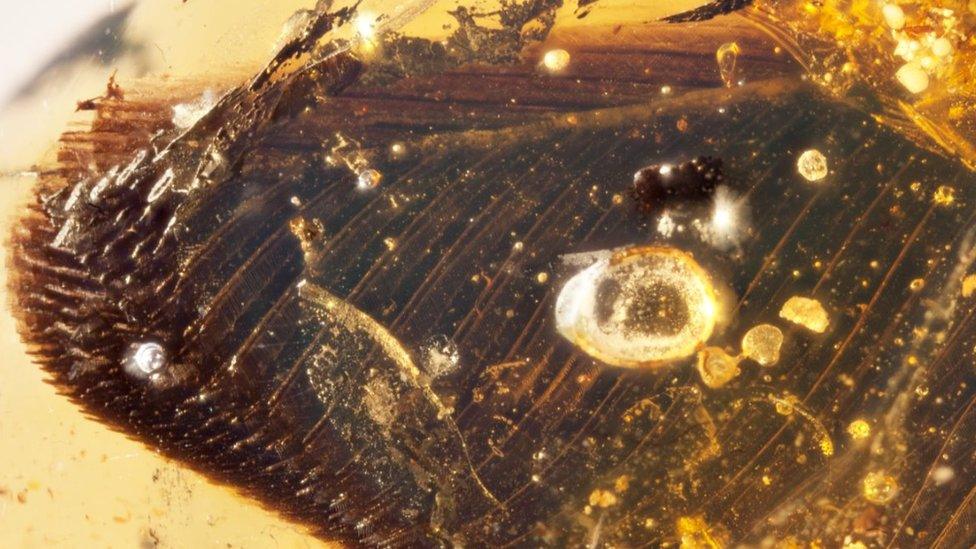

The finds show that the ancient birds had very similar wing and feather arrangements to living examples

Two wings from birds that lived alongside the dinosaurs have been found preserved in amber.

The "spectacular" finds from Myanmar are from baby birds that got trapped in the sticky sap of a tropical forest 99 million years ago.

Exquisite detail has been preserved in the feathers, including traces of colour in spots and stripes.

The wings had sharp little claws, allowing the juvenile birds to clamber about in the trees.

The tiny fossils, which are between two and three centimetres long, could shed further light on the evolution of birds from their dinosaur ancestors.

The wings possessed little claws to allow the birds to climb around in trees

The specimens, from well-known amber deposits in north-east Myanmar (also known as Burma), are described in the journal Nature Communications.

Co-author Prof Mike Benton, from the University of Bristol, said: "The individual feathers show every filament and whisker, whether they are flight feathers or down feathers, and there are even traces of colour - spots and stripes."

The hand anatomy shows the wings come from enantiornithine birds, which comprised a major bird grouping in the Cretaceous Period. However, the enantiornithines died out at the same time as the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago.

Dr Steve Brusatte, a vertebrate palaeontologist at Edinburgh University, described the fossils as "spectacular".

Overlapping flight feathers can be seen erupting from the amber

Colour differences in the birds' plumage can be clearly seen

He told BBC News: " They're fantastic - who would have ever thought that 99-million-year-old wings could be trapped in amber?

"These are showcase specimens and some of the most surprising fossils I've seen in a long time. We've known for a few decades that many dinosaurs had feathers, but most of our fossils are impressions of feathers on crushed limestone slabs.

"Three dimensional preservation in amber provides a whole new perspective and these fossils make it clear that very primitive birds living alongside the dinosaurs had wings and feather arrangements very similar to today's birds."

Fine structure in the feathers has been exquisitely preserved

The international team of researchers used advanced X-ray scanning techniques to examine the structure and arrangement of the bones and feathers.

Claw marks in the amber suggest the birds were still alive when they were engulfed by the sticky sap.

Dr Xing Lida, the study's lead author, explained: "The fact that the tiny birds were clambering about in the trees suggests that they had advanced development, meaning they were ready for action as soon as they hatched.

"These birds did not hang about in the nest waiting to be fed, but set off looking for food, and sadly died perhaps because of their small size and lack of experience.

"Isolated feathers in other amber samples show that adult birds might have avoided the sticky sap, or pulled themselves free."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external