Heady days for ocean surface mappers

- Published

The satellites pass over the warmer, higher (red) waters of the Gulf Stream on the same day

This is an unprecedented time for the study of the oceans.

Space agencies are now flying six satellite altimeters, returning large volumes of data on the height and shape of the sea surface - and in rapid time.

The information is fed into all manner of applications, from forecasting the weather to understanding the migratory habits of marine creatures.

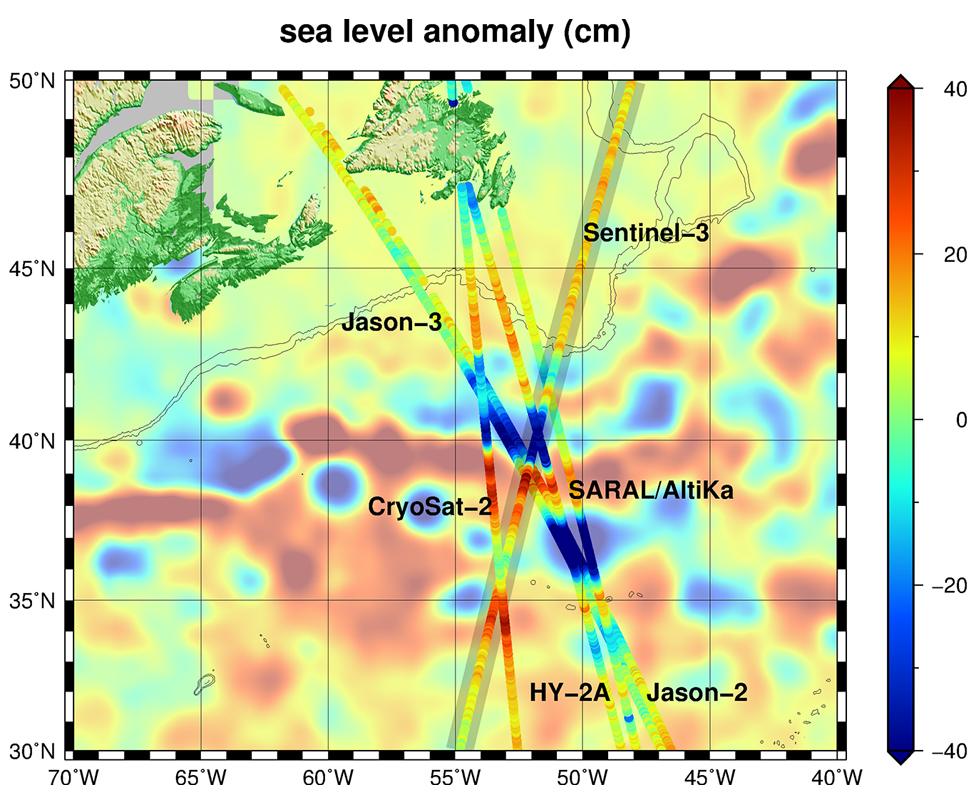

The main image at the top of this page gives a snapshot of the six missions in action as they monitor the North Atlantic.

Each is seen to fly over the Gulf Stream - the current of warm water that rides up the East Coast of the US and then crosses to Europe.

The background map is a model - based on some of the sextet's data - of what the ocean was doing on the day the satellites tracked through the scene.

It should be evident immediately that the spacecraft all see the same features.

Remko Scharroo: "We now have unprecedented coverage of the oceans"

The constellation comprises the satellites known as Jason 1 and 2, which are a joint effort between the US and Europe; Sentinel-3a and Cryosat, which are solely European ventures; Saral/Altika - a French-Indian project; and HY-2A from China.

Their equipment may differ slightly, but their principle of operation is the same: they emit radar pulses towards the sea-surface and catch the "echo".

The nature of the returning energy gives information on the state of that surface, providing indications of wind speed and wave height. Meteorological agencies feed this into the numerical models that produce our weather forecasts.

But the time to the arrival of the echo is also a measure of the elevation of the surface - and is useful in a couple of ways, says Remko Scharroo, an altimetry expert with Eumetsat, the organisation charged with gathering the satellite information for Europe's forecasters.

"First of all, you can look at the slope of the sea surface and that tells you something about the currents. And secondly - the total height also depends on the total energy in the ocean.

"You can imagine that if you heat up the ocean, it slightly expands. And that's very important for example in hurricane forecasting because this type of information will tell you how much energy a hurricane can absorb from the ocean. If the sea surface is warm but the underlying water is not, the hurricane will not be intensified as much."

Watch each satellite track across the Gulf Steam

And it all goes wider than just the met offices, of course.

Shipping companies take the current information to work out the most efficient routes, saving time and diesel.

Drill rigs and cable-laying vessels will monitor strong currents and surface eddies to plan sensitive operations.

Marine biologists are interested in the surface conditions and currents because these hint at how water is being moved and mixed.

This influences the distribution of nutrients in the ocean and the production of plankton. All higher life - from the smallest fish to the biggest whales - depends on such processes.

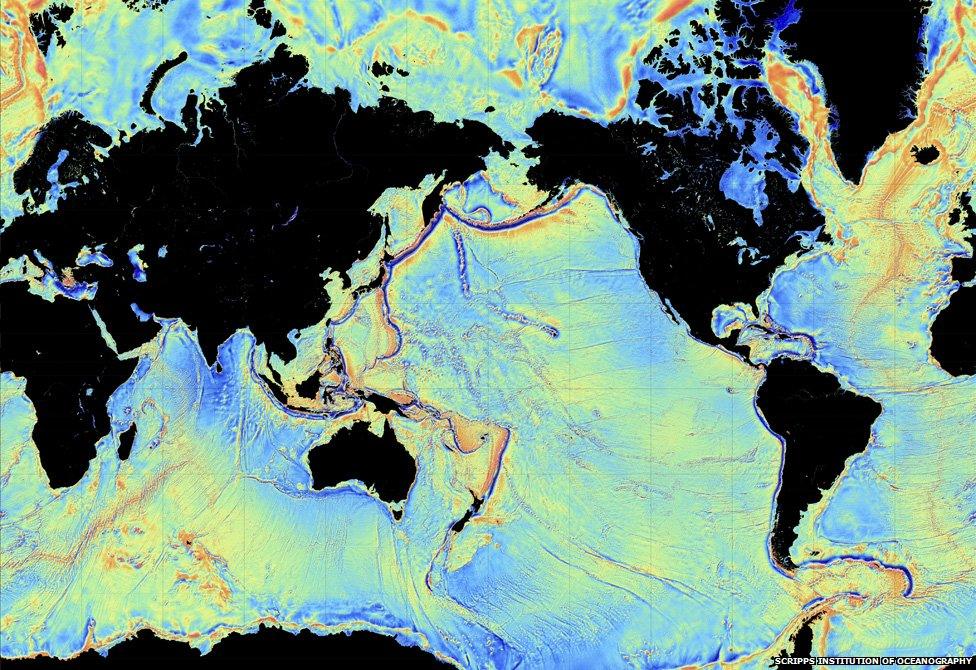

Even geologists have reason to thank the work of the satellite altimeters.

This is because the mean topography of the sea surface reflects the shape of what lies below.

Because water follows gravity, it is pulled into highs above the mass of tall seamounts, and slumps into depressions over deep trenches.

Most of our knowledge of what the ocean floor looks like relies on these altimetric interpretations.

The two newest missions, Jason-3 and Sentinel-3a, are currently going through a period of commissioning before being accepted into full operation.

They were launched in January and February, respectively.

In the Gulf Stream map, Jason-3 is seen to track very close to its predecessor Jason-2 so that their instruments can be cross-calibrated.

Eumetsat has a key role in the management of the data coming from both the Jason and Sentinel missions.

Satellite altimeters use the mean sea-surface topography to infer the shape of the ocean floor

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published17 June 2016

- Published2 March 2016

- Published17 January 2016

- Published10 May 2016