Juno mission: British rocket engine ready for Jupiter task

- Published

An artist's impression of Juno firing its Leros-1b engine at Jupiter

When the US space agency's latest probe to Jupiter tries to enter into orbit around the planet on Tuesday, it will be relying on a British rocket engine.

The Juno satellite, external is rapidly bearing down on the gas giant after a five-year journey from Earth.

It must slow itself to get captured by the gravity of the giant world.

This all-or-nothing job will be performed by its Leros-1b engine built by Moog-ISP in Westcott, Buckinghamshire.

"It's a tremendous thing for us," said Moog's chief engineer, Dr Ian Coxhill.

"The engine has to work for Juno to get into orbit; it has to burn at a precise time and burn for a continuous duration of at least 20 mins.

Westcott has a proud history in the development of rocket engines

"There'll be some frayed nerves, for sure."

The Leros-1b was chosen to be the main engine on the Nasa satellite by its manufacturer, Lockheed Martin.

Previous American space agency missions have also used the Westcott technology, including the Messenger probe that went into orbit around Mercury in 2011. So, there is high confidence this latest engine will be up to the task.

Indeed, Juno has already fired it during the epic journey to Jupiter.

Back in 2012, the Leros had to operate reliably twice to refine the trajectory of the spacecraft, and on each occasion the engine burned flawlessly for more than 20 minutes.

"In fact, things went so well that Lockheed Martin said initially they thought they had confused the real flight data on the engine burn with the simulation data. It was that accurate. So that's obviously really encouraging," Dr Coxhill told BBC News.

The Jupiter Orbit Insertion manoeuvre will be conducted in the early hours of Tuesday morning, British time.

Juno will turn and fire the Leros in the forward direction to try to remove about 500m/s from its velocity - enough so that it goes into a 53-day orbit around the gas giant.

No burn or a burn of insufficient length would send Juno into the oblivion of deep space.

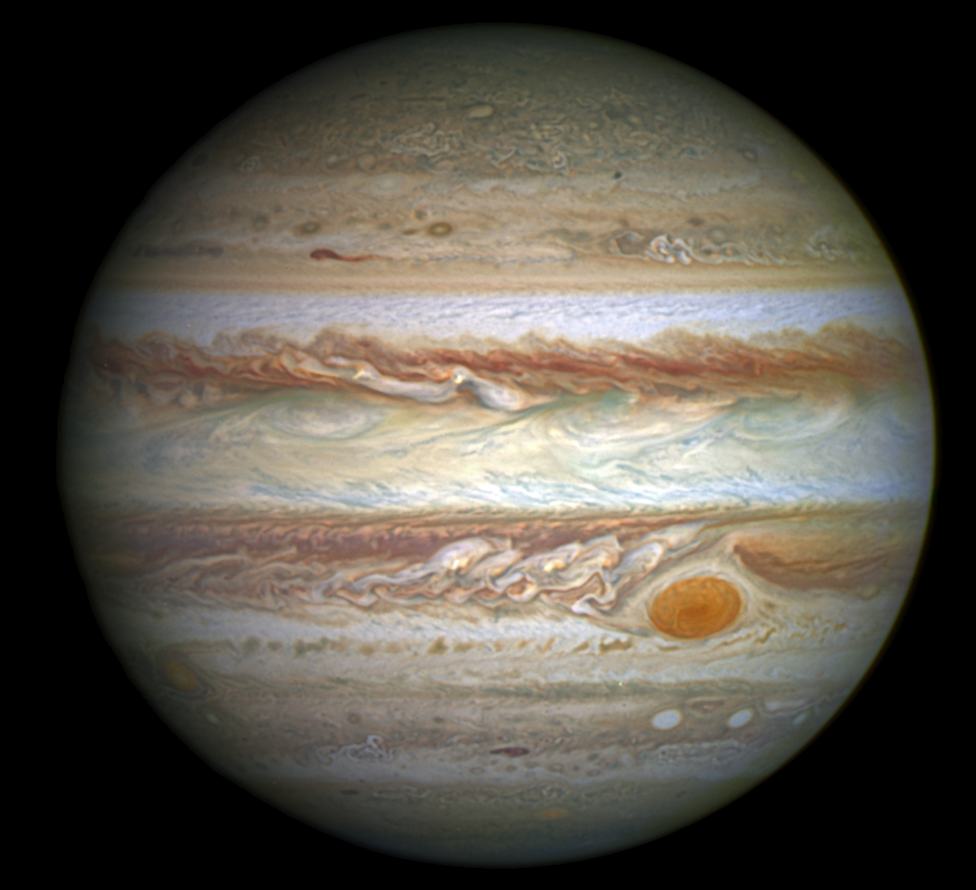

Juno will reveal new details about the Great Red Spot

The probe will send back a series of tones to update Nasa and Lockheed Martin engineers on the progress of the insertion.

The Leros should light at 04:18 BST (03:18 GMT) and terminate at 4:53 BST (03:53 GMT), for a full firing of 35 minutes in length.

These are what are called Earth-receive times, when the confirmation tones are picked up by Nasa's antenna network.

In reality, they will be listening 48 minutes in arrears because of the vast distance - 849 million km - the radio signals will have had to travel from Jupiter.

And this means of course that the whole event is actually reported at Earth after it is all over.

Juno will therefore have to rely on its automated systems to troubleshoot any problems that might arise during the firing.

"The system is designed so that if, for instance, the radiation at Jupiter causes the computer to re-set and the engine to stop… it will do a quick recycle and restart the burn. We expect to get all the way to 35 minutes," said Rick Nybakken, Nasa's project manager on Juno.

Another burn in October will tighten the initial orbit to one of two weeks from which the spacecraft can then conduct its science observations.

No probe has ever got as close to Jupiter as this mission will go.

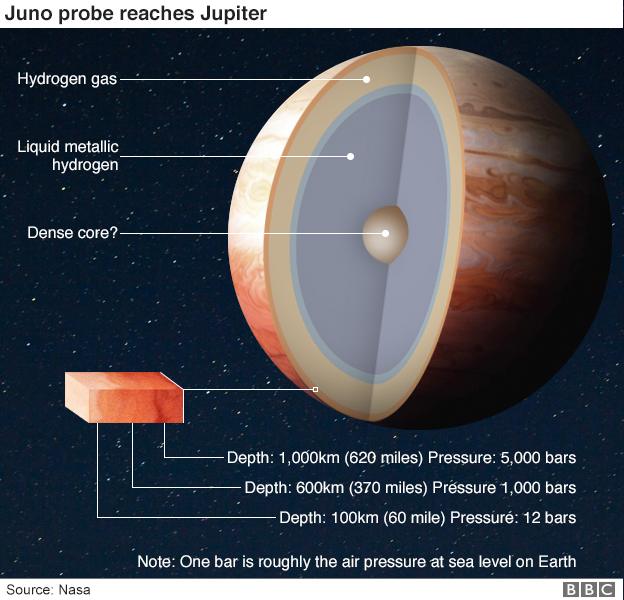

Its goal will be to look down on the colossal world to work out what it is made from and how it is put together.

We should finally discover whether it has a solid core or if its gas merely compresses to an ever denser state the closer you get to the centre.

We should also gain new insights on the famous Great Red Spot - the monster storm that has raged on Jupiter for hundreds of years. Juno will tell us how deep its roots go.

But all this future knowledge depends on the 35 minutes of thrusting from the British engine.

Principal investigator Scott Bolton will be following events here at Nasa's mission control, at the Jet Propulsion laboratory in Pasadena, California.

"We're excited to be finally getting to Jupiter but I have to temper that emotion with anxiety and the giant risk that we're facing because everything's got to go just right," he told BBC News.

"It's a very complicated manoeuvre, the rocket has to fire at just the right time for the right amount of time and in the right direction for us to get into orbit. So, everything to do with this mission is riding on the activities of 4 July (California time)."

There will be constant updates on Juno's orbit insertion across BBC News, and the BBC Sky At Night programme will run a special programme dedicated to the mission on Sunday 10 July at 20:30 BST, on BBC Four.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external