Has the LHC discovered a new particle?

- Published

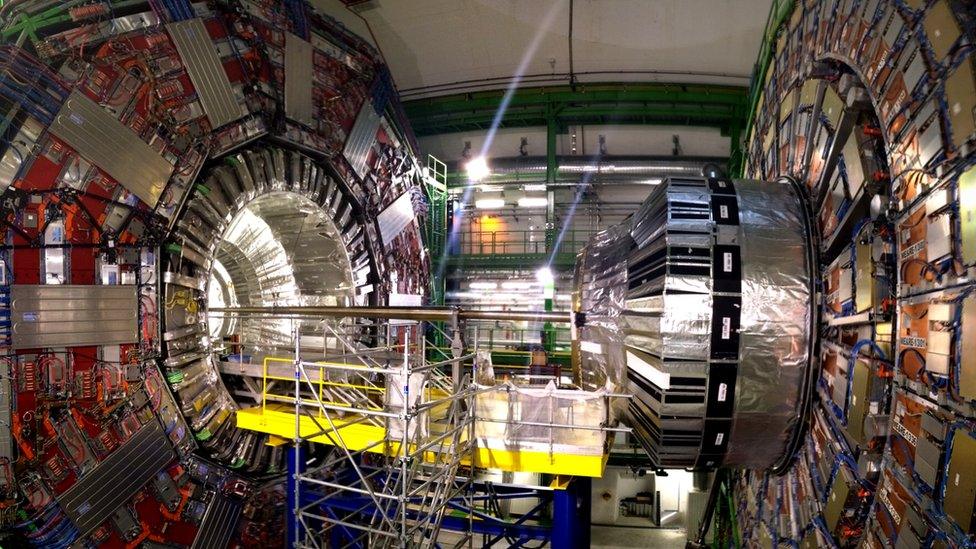

A giant depiction of the CMS experiment adorns the atrium of building 40 at Cern

After its much heralded re-start last year, has the world's biggest machine, the Large Hadron Collider, found a new particle?

You could be forgiven for thinking that things had gone a little quiet at Cern in Switzerland after the LHC was switched on to great fanfare in April 2015.

But physicists have been hard at work crunching data collected by the world's most powerful particle accelerator, which is now operating at unprecedented levels of energy and intensity.

Their efforts may not have been in vain, because there has been growing excitement in the hallways and offices at Cern in Geneva over a so-called "bump" in the data from the LHC's particle collisions.

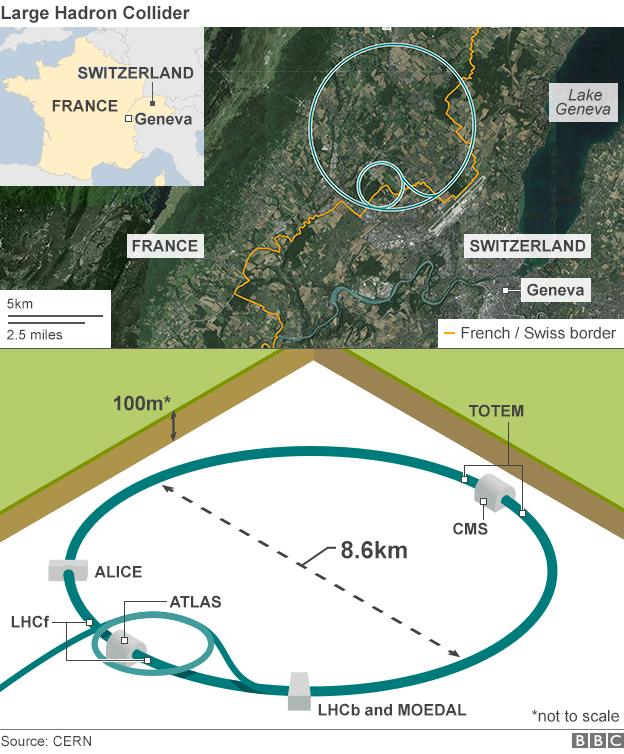

The LHC smashes two beams of proton particles together about 100m beneath the French-Swiss border. Scientists then scour the debris of these smash-ups for hints of previously undiscovered particles.

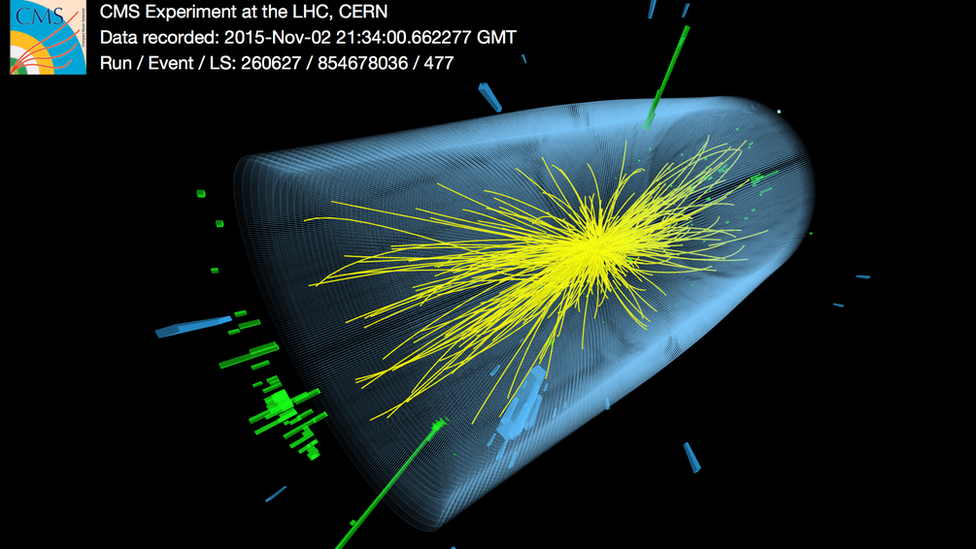

Last year, out of trillions of such collisions, scientists detected more photon (light) particles being produced than expected - the aforementioned "bump". More precisely, they saw an excess of photon pairs with a combined mass of 750 Gigaelectronvolts (GeV), external.

This could be the tell-tale sign of a new, heavy particle that's about six times more massive than the famed Higgs boson - discovered at Cern in 2012.

The discovery of a new particle would be so exciting because the most widely accepted theory of particle physics, the Standard Model, can't explain everything we observe about the world around us.

LHC facts

The Large Hadron Collider is a particle accelerator that pushes two particle beams to near the speed of light and smashes them together so that scientists can look for signs of new physics phenomena in the debris

More than 1,200 "dipole" magnets are arranged end-to-end in a 27km-long circular tunnel 100m under the French-Swiss border near Geneva.

The magnets steer the beam of either proton particles or lead ions around the LHC's ring. At allotted points around the tunnel, the beams cross, allowing collisions to take place.

The experiments that analyse these collisions, generate more than 10 million gigabytes of data every year.

It says nothing, for example, about dark matter - the mysterious stuff that makes up some 27% of the Universe. So scientists at Cern are searching for hints of new physical phenomena which could lead the way to a deeper understanding of the cosmos.

Signals have come and gone since the LHC first went online back in September 2008. Such statistical fluctuations are expected, and the bumps usually get ironed out with the addition of more data.

"More data is needed to be sure the signal doesn't go away - until then we have to be cautious," explained Prof Stefan Söldner-Rembold, head of particle physics at the University of Manchester.

"The big reason that people are excited about this bump is that both experiments (Atlas and CMS) saw a hint in roughly the same place. But even this is not completely unlikely."

Atlas (pictured) and its counterpart CMS both saw hints of a particle in the same place

The gold standard for claiming a discovery in particle physics is a statistical threshold known as five sigma. This corresponds to a chance of one in 3.5 million that the observed signal is a fluke, and roughly the same likelihood as tossing a coin and getting 21 or 22 heads in a row.

A slew of scientific papers seeking to explain the anomaly have been uploaded to the Arxiv pre-print server, external in recent months. However, in the last few weeks, rumours have begun to circle on blogs about the signal fading as the latest data from the LHC are analysed.

Later this summer, the LHC experiments will present their newest results at a conference in Chicago with significantly more data. Indeed, officials at Cern said the LHC has already accumulated more data in 2016 than it did last year.

So the coming weeks will be crucial for telling whether the 750 GeV signal is a simple mirage or something more.

But what we do know about the putative particle already restricts the possibilities.

Physicists see an excess of photon pairs at 750 GeV, the possible decay products of a new particle

If it's there, we know that it decays to two photons (light particles) and that, consequently, it must have a "spin" of either zero or two. In physics, spin is a quantum mechanical property of elementary particles which has several practical applications, such as in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

If the particle's spin is zero, like the Higgs boson, it could potentially be a heavier cousin of that particle discovered in 2012.

Another possibility, that the particle carries a spin of two, has led to the idea it could be a form of the graviton, external - a purely theoretical particle which imparts the fourth force, gravity. Gravity is one of the big puzzles in physics that remain unexplained by the Standard Model.

But some physicists are sceptical that a particle like the graviton answers the problem, and favour other explanations to the fourth force.

Many physicists working at the LHC have been looking hard for confirmation of a leading theory known as supersymmetry, external. The idea proposes the existence of hitherto unseen "partner" particles to those in the Standard Model, external. The Higgs' supersymmetric partner is dubbed the Higgsino, the gluon's is known as the gluino and so on.

Over 1,000 dipole magnets steer two particle beams around at close to the speed of light

But whatever the 750 GeV signal is, physicists are fairly sure it isn't the first supersymmetric particle.

"Something that you cannot incorporate in a known theory of physics can be very exciting because it means there's something fundamental that's not understood," Prof Söldner-Rembold explained.

And if a particle is confirmed, it shouldn't be alone.

"Ideally, if this is an indication of some new sector, then new particles should show up at similar scales or higher," he added.

The absence of any evidence for supersymmetry at the LHC so far has led to some simple versions of the theory being excluded, while others are being put under pressure. But adherents of the idea say there is still a vast amount of open territory still to be explored at the LHC.

"Supersymmetry isn't something people just made up. It addresses certain problems in the Standard Model which remain unsolved," said Prof Söldner-Rembold, adding that we shouldn't give up on the idea yet.

And whether the 750 GeV "bump" turns out to be something real, or not, the Manchester University particle physicist stresses that the LHC is a long-term endeavour with decades still to run.

Despite the relative swiftness with which the LHC discovered the Higgs boson, this was never going to lead to a bonanza of discoveries every year. Perhaps we should get used to the idea that the Universe isn't going to give up its secrets so easily.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

- Published5 March 2015