Pneumatic octopus is first soft, solo robot

- Published

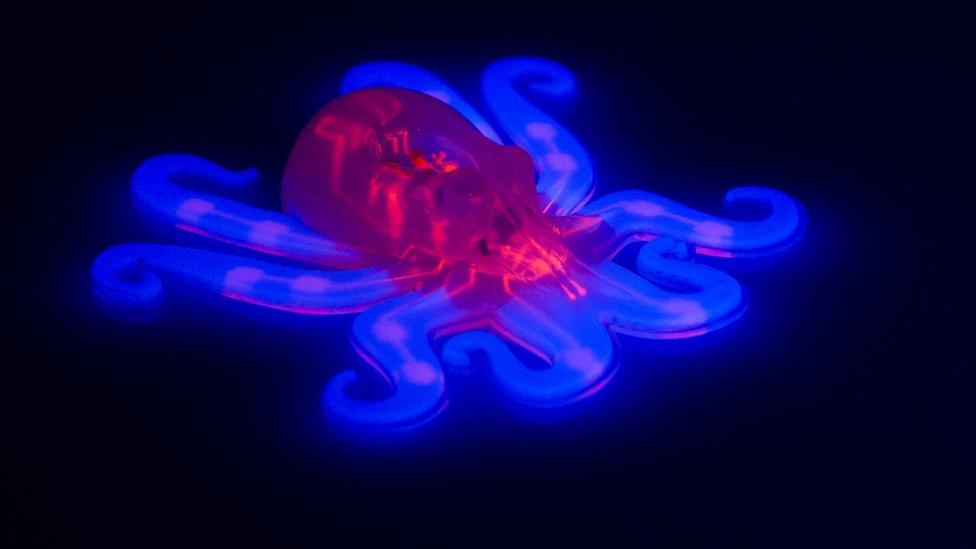

Meet the "octobot": 7cm across and full of potential

US engineers have built the first ever self-contained, completely soft robot - in the shape of a small octopus.

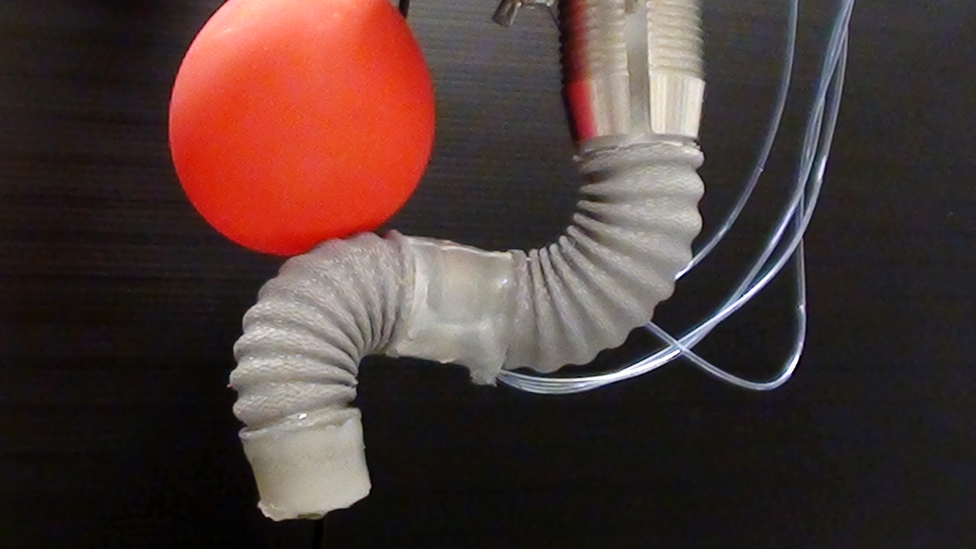

Made from silicone gels of varying stiffness, the "octobot" is powered by a chemical reaction that pushes gas through chambers in its rubbery legs.

Because of this design, the robot does not need batteries or wires - and contains no rigid components at all.

Instead, a sequence of limb movements is pre-programmed into a sort of circuit board built from tiny pipes.

These movements aren't good enough, yet, to send the octobot out for a stroll; instead it sits in one place and pumps alternating legs up and down in a very slow, eight-legged can-can.

But because that dance is powered purely by the robot's internal pneumatic system, the Harvard researchers - writing in the journal Nature, external - say their system marks a key step forward for soft robotics.

"Many of the previous embodiments required tethers to external controllers or power sources," said PhD student Ryan Truby from Harvard University.

"What we've tried to do is actually to replace these hardware components entirely and have a completely soft robotic system."

The hope is that one day, soft robots will wiggle their way into awkward surgical locations or squeeze under obstacles on search-and-rescue missions.

Real-world tasks like these, particularly if they involve human interaction, are challenging or even impossible for conventional, rigid robots - which are much more comfortable in the structured, repetitive environment of the factory floor.

Some of the prototypes were loaded with fluorescent dyes to show off their internal features

"Where everybody's really excited to see soft robots come in is right at the human-robot interface," Mr Truby told BBC News.

"Humans ourselves, we're very soft… and soft robots are made of materials that are safe for us to interact with."

The octopod is certainly pliable. It was made entirely from different types of silicone gel using a carefully devised combination of moulding and 3D printing.

'We finally did it'

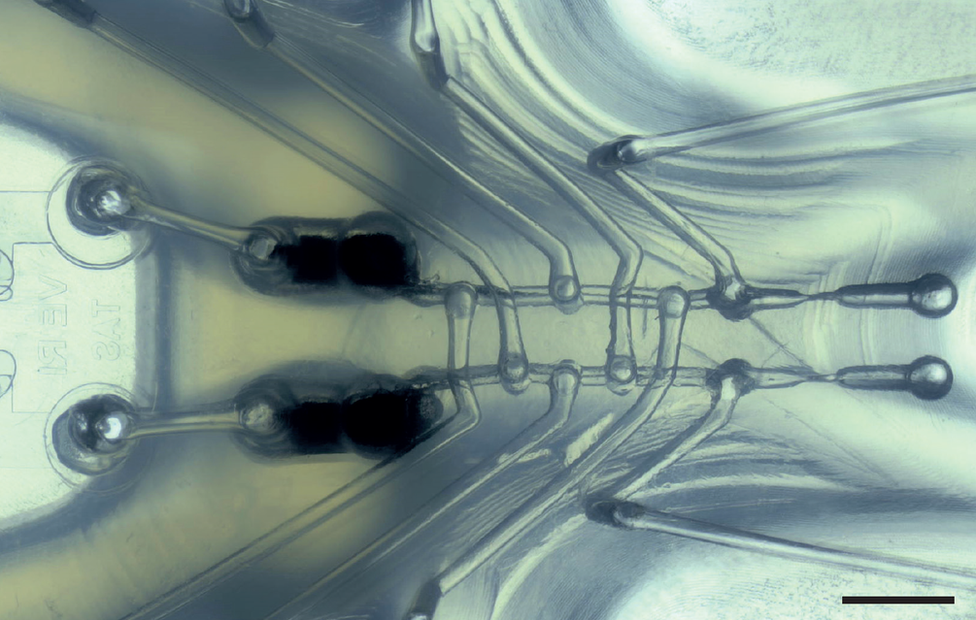

At its heart is a "fluidic logic circuit" where valves act as logic gates, allowing gas to flow and inflate compartments inside the eight separate limbs.

The gas is pumped into that circuit by a little fuel cell filled with hydrogen peroxide, which reacts with particles of platinum left in the system by the printing process.

All Mr Truby and his colleagues had to do - after several years perfecting the design - was to fill the robot with fuel and watch it go.

"We had all the components in place for quite a while, and it took many months trying to bring it all together," he said.

"It was back, I guess last October, there was this one day when it just started working. Michael [Wehner, co-first author] and I looked at each other and thought: OK, we finally did it.

"Several iterations later, we kept fine tuning, and at one point we could just take these things out of the oven, fill them up with fuel and they'd start moving."

A network of channels sits at the core of the robot (black bar is 2mm long)

The circuit sets up an alternating movement, whereby balloon-like chambers are inflated inside four limbs at a time.

The octobot raises four legs and lowers the other four, then swaps. It is a simple demonstration but an important one.

"Right now he's kind of flopping back and forth, but it'd be nice to create soft robots that know when they're interacting with their environment - that have more complicated modes of autonomous functionality," Mr Truby said.

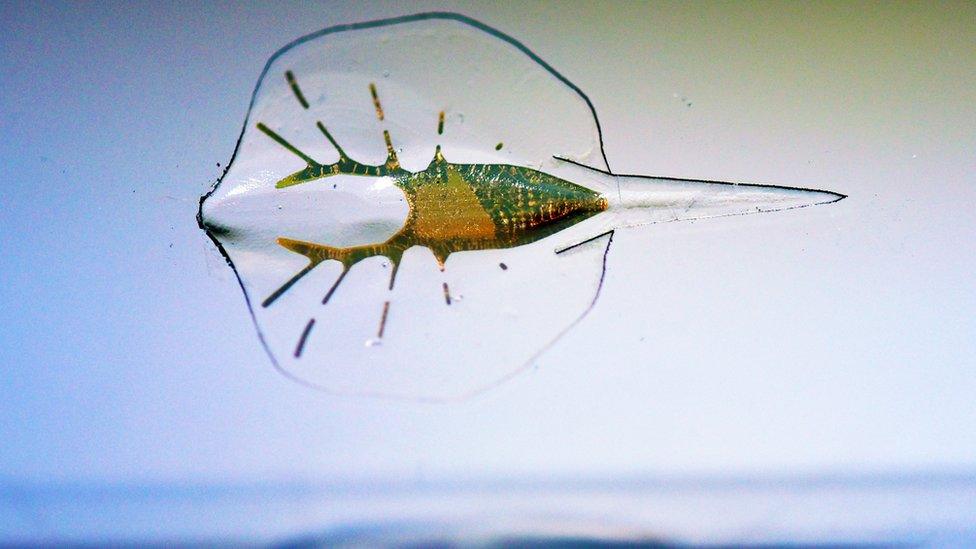

And why make the prototype an octopus? As a tribute, apparently. The animal is devoid of a skeleton but remarkably strong and capable of a baffling variety of movement - so has been a tremendous model for the soft robotics community.

"The octopus itself does not move this way, it is not powered this way," Mr Truby explained.

"We're not necessarily taking inspiration from the octopus itself, but we thought that for... our first embodiment of an entirely soft robot, it needed to have the form of an octopus."

The octobot: More of a tribute than a replica

Jonathan Rossiter, who runs the soft robotics group at the Bristol Robotics Lab, external, said the Harvard team had achieved something unique.

Researchers around the world, he said, have been working on the various components of an entirely soft robot: inflatable "muscles", fuel cells, soft sensors and control systems.

"One thing that's been missing so far has been putting them all together," Prof Rossiter told the BBC, adding that the octobot would be a springboard for others in the field.

"It's made in a really nice way. It's made in a way that other people can look at and say, we could use these technologies ourselves - we can make ones that have better fuel systems, or have better control systems, or a more sophisticated body.

"This is a good demonstration of bringing everything together. That's not easy, and they've done a good job."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published8 July 2016

- Published14 May 2015

- Published12 March 2015

- Published4 April 2014

- Published16 August 2012

- Published28 November 2011