North Atlantic 'weather bomb' tremor measured in Japan

- Published

The same "weather bomb" brought violent weather to the north-west of the UK

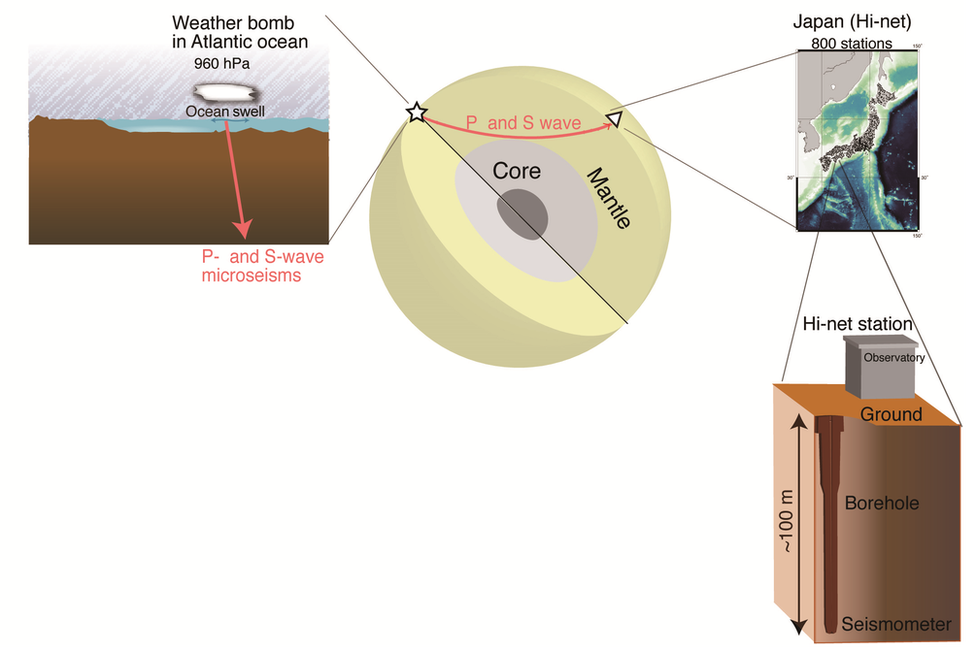

Seismologists in Japan have tracked, for the first time, a particular type of tiny vibration that wobbled through the Earth from the Atlantic seafloor.

It was started by a "weather bomb": the same low-pressure storm, off Greenland, which made UK headlines in late 2014.

Tiny tremors, of two types, constantly criss-cross the deep Earth from storms.

The slowest of these, the "S" wave, has never been traced to its source before and researchers say it opens up a new way to study the Earth's hidden depths.

The findings appear in the journal Science, external.

Weather-triggered waves in the fabric of our planet, known as "microseisms", happen whenever a storm at sea crashes waves together and those collisions send energy booming into the ocean floor.

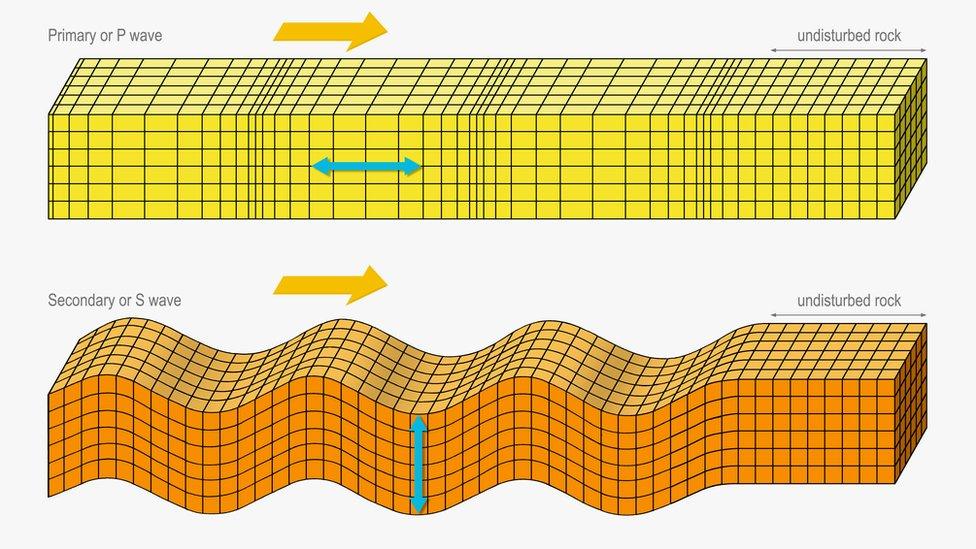

The energy then spreads through the Earth as two very faint types of wave:

a pressure or "P" wave, with successive ripples of squeezing and expanding

a transverse or "S" wave, which travels slower and wobbles the rock from side to side

When an earthquake occurs, it radiates more violent versions of the same two waves. The P waves arrive first, and can be sensed by seismometers and some animals; the S waves arrive second and do the serious shaking.

Earthquakes and storms both trigger two types of disturbance in the Earth

In the case of microseisms, both signals are faint but P waves have been more straightforward to study. Typhoons in the western Pacific, for example, generate signals that are routinely picked up by scientists in California.

Key to finally picking up and pinpointing the more elusive S waves was deploying a big suite of detectors.

Kiwamu Nishida from the University of Tokyo and Ryota Takagi of Tohoku University used a network of 202 stations in the Chugoku region of southern Japan.

This high-density array allowed them to add up many measurements of the same very faint signals, and eventually trace their source all the way back to the north Atlantic.

Signals from the Atlantic were sensed by instruments buried in boreholes in Japan

Peter Bromirski, from the University of California San Diego, was not involved in the research but co-wrote a commentary on it in the same issue of Science, external.

He said that being able to detect both S and P waves from storms would open up more of the Earth to the prying ears of seismologists.

"Most of what we know about the internal structure of the Earth has been determined from studying the way earthquake waves propagate, through the lower crust and the mantle and the core," Dr Bromirski told Science in Action on the BBC World Service.

"In order to do that, you need to have a source that can generate a signal that propagates to your seismic stations. For some reason there are very few earthquakes in the mid Pacific... so we don't have any sources there.

"These storm-generated P and S wave microseisms will hopefully allow us to better characterise the structure of the Earth below the Pacific."

How often do they get it right?

Forecasters have a chequered reputation, but do they deserve it?

Current five-day forecasts are as reliable as three-day ones from 20 years ago

Forecast accuracy varies with the season, and weather types

- Published10 December 2014