Mary Rose shipwreck skulls go online in 3D

- Published

From the depths of the Solent... to the internet

For the first time, skulls and other artefacts from the 1545 wreck of Henry VIII's warship the Mary Rose are being exhibited online as 3D reconstructions.

Researchers from Swansea University unveiled the scans to coincide with the British Science Festival, external, taking place in the Welsh city this week.

Some of the virtual objects are public, external while others are for research purposes.

The idea is to see how much can be learned about the lives of the ship's crew, just from their digitised bones.

Richard Johnston, a materials engineer at Swansea, said the project would test the scientific value of digital archaeology - and the world's burgeoning collection of cyber-artefacts.

"Lots of museums are digitising collections, and a lot of the drive behind that is creating a digital copy of something," Dr Johnston told journalists at a press briefing in London.

"We're going to challenge the research community to see if they can actually do osteological analysis.

"Then we will take the results from around the world and try and compare those to a study that we did, where people looked at the real remains."

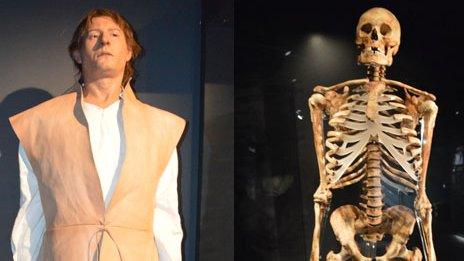

The public website virtualtudors.org,, external launched on Monday, offers an interactive view of one particular skull from the Mary Rose crew - that of a carpenter found on the ship's lower deck - as well as several of his possessions.

A separate, research-focussed section of the site will make a further nine skulls available to bone specialists around the world.

More on digital archaeology:

Each participant will be given a questionnaire to see what their assessment is of the skulls, which the UK team will then compare.

If the results are good, Dr Johnston said, they might help tackle scepticism from some in the field who insist that physically interacting with specimens is essential.

"Do you really need to hold the skull, or can you tell a lot from the digital one? There's the potential to speed up science dramatically - but this needs to happen first."

The carpenter was found on the orlop deck, just above the hold

Because the pool of expertise can be much wider once resources like these are online, there is also the possibility that a new discovery will emerge.

"It might be that somebody in, I don't know, Arizona, has a particular speciality and they say, 'Do you realise that this person here has such-and-such a condition?' It'd be very nice if that happened," said Swansea biomechanist Nick Owen, who has previously studied the skeletons of archers from the Mary Rose.

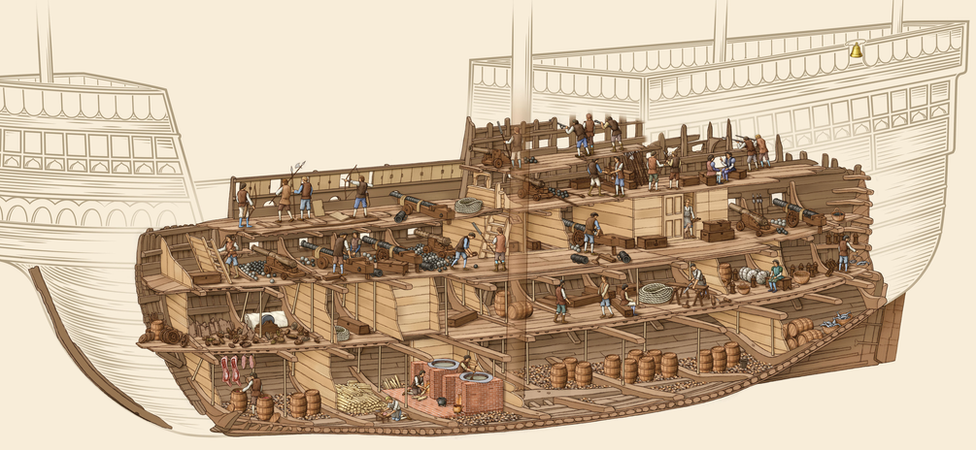

When the ship sank 471 years ago, it was leading the attack on an invading French fleet north of the Isle of Wight.

Discovered in 1971 and raised in 1982, the wreck is a famous time capsule of Tudor times, yielding around 19,000 artefacts and 179 skeletons.

Restoring and exhibiting the Mary Rose was a mammoth archaeological effort. A new display of the remains of her hull was unveiled in July in a purpose-built museum in Portsmouth.

It includes projected vignettes of crew members moving among the ship's timbers.

The Mary Rose exhibit in Portsmouth reopened in July

"We've sort of got a virtual ghost ship, with people walking around it and doing things," said Alex Hildred from the Mary Rose Trust.

"And now we hope to have a virtual population that people can interact with online and that researchers, hopefully, may be able to help us build into more complete individuals."

One of those highlighted crew members is the same carpenter whose skull is the centrepiece of the new website.

Found with his tools, he was probably in his mid-thirties and suffered arthritis and bad teeth. Carpenters like him worked on the lower decks to repair damage during battle.

After more than four centuries at the bottom of the Solent, this carpenter's journey to 3D reconstruction and internet fame has been painstaking and precise.

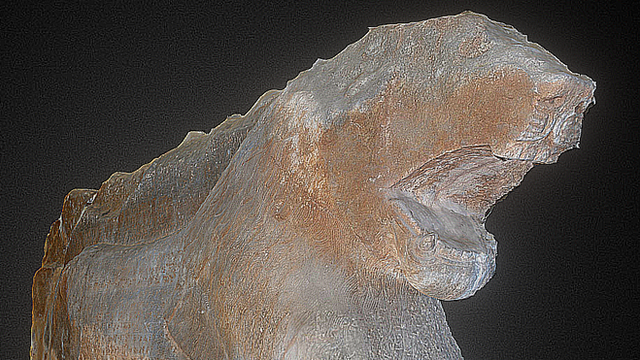

Some 120 photos were taken of his skull, and each of the others, using a 39-megapixel camera.

"It was probably about a day of photographing per skull," said student Sarah Aldridge, who did most of this work herself as part of her PhD research at Swansea University.

"It got a little bit quicker as it went through."

The skulls and artefacts - like this wooden panel - were photographed on a green-screen backdrop

Once the snaps were taken, the business of "photogrammetry" began: Ms Aldridge used software to edit, align and combine all the images into a 3D representation - now visible online in 15-megapixel glory.

This is compressed, but still very detailed.

"It's a lot of data that's been compressed into an object to give us what we think is probably, currently, the best that can be done with photogrammetry in terms of resolution and quality," said Mr Owen.

All of this effort, the team hopes, will give the virtual bones the best chance of performing well in the study.

"What we're doing with our website is... to draw a line in the sand," Mr Owen said.

"How much information can we get? How useful is photogrammetry, for osteology, with the current state of the art?"

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published19 July 2016

- Published10 October 2015

- Published19 May 2015

- Published16 December 2014

- Published16 December 2014