'Cyber-archaeology' salvages lost Iraqi art

- Published

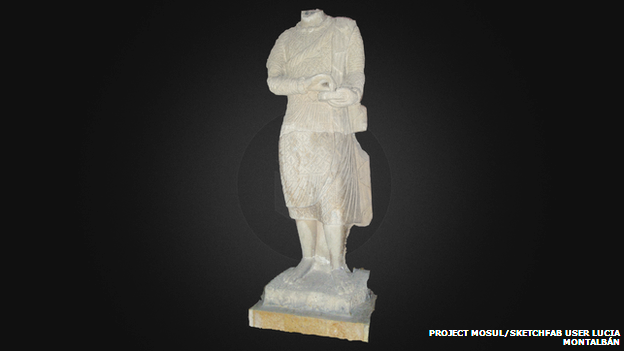

3D reconstructions are assembled from digital photos

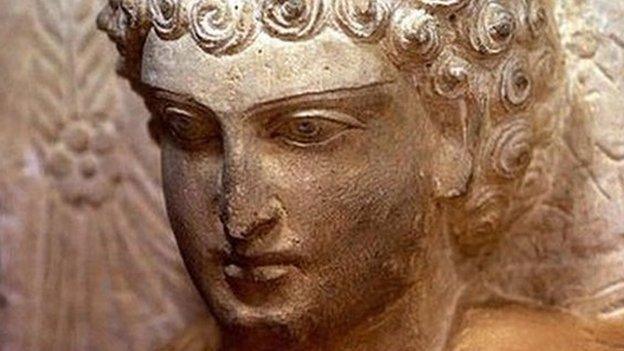

Priceless historical artefacts have been lost recently, to violence in Iraq and earthquakes in Nepal. But "cyber-archaeologists" are working with volunteers to put you just a few clicks away from seeing these treasures - in colourful, three-dimensional detail.

The effort began with a conversation between two young researchers in late February, days after shocking footage emerged of Islamic State militants tearing down and smashing artworks in the Mosul Museum in northern Iraq.

Chance Coughenour and Matthew Vincent are PhD students working for the Initial Training Network for Digital Cultural Heritage (ITN-DCH, external), an EU-funded project set up to apply new technology to cultural heritage issues.

"We were talking about the destruction and [Chance] suggested that we crowd-source the reconstruction of these images, using photogrammetry and images from the public," Mr Vincent told the BBC's Science in Action programme.

Photogrammetry is a popular technique in modern cultural heritage projects. It uses software to turn multiple 2D photographs of a single object into 3D images.

"It's an incredibly useful technology that can create 3D models just using photos from a normal digital camera," explained Mr Vincent.

He and his colleague realised that if they could find enough photos of the destroyed artworks, they could salvage them in cyberspace.

So they set up Project Mosul, external. People who have visited now-destroyed sites - beginning with the Mosul Museum - can submit their photographs. Then volunteers log on to help sort the images, and those with the know-how get stuck into the job of rebuilding the artefacts.

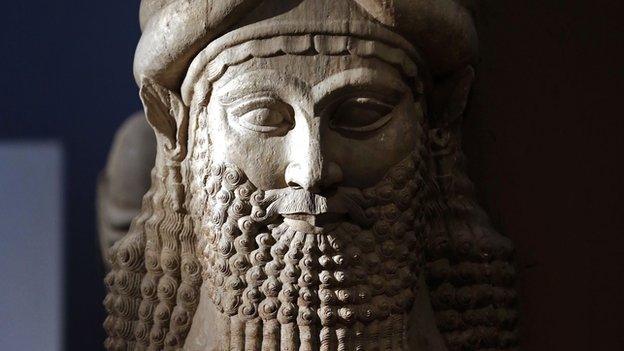

Cuneiform text can still be read on the side of this lion statue from the Mosul Museum

The project has received more than 700 photos so far, including 543 showing artefacts from Mosul. A gallery on the homepage, external displays 15 3D reconstructions, completed by nine volunteers.

"We have others who are anxious to learn how to do photogrammetry and to help out," said Mr Vincent, adding that his main hold-up at the moment is finding the time to manage and develop the platform.

The nine volunteers have used their choice of software to construct the replicas, and then uploaded them via the 3D sharing platform Sketchfab, external.

The obvious favourite in the gallery so far is a lion from the Mosul Museum. When the statue itself was still standing, it was clearly also a popular subject for visitors to photograph. Some 16 photos of the lion were received, which allows for quite a detailed reconstruction.

"The more photographs you have, the more potential you have to create more 3D points and have a denser cloud," said Mr Vincent.

Because more images make for better models, the project has even made available some pictures from the original ransacking footage, because they may help with the reconstruction process.

Unknown losses

The final results don't quite match what scientists could achieve if they had scanned the artefacts with specialist equipment, but they are an impressive piece of crowd-sourced digital rescue work.

"These models don't have the same scientific value as if we were able to do this with calibrated cameras, laser scans, etc. But the 3D models still have the value of the visualisation - being able to see what the artefact was like.

"We can recreate the experience of being in the museum, in cyberspace."

Images from the Mosul video itself are now part of the reconstruction effort

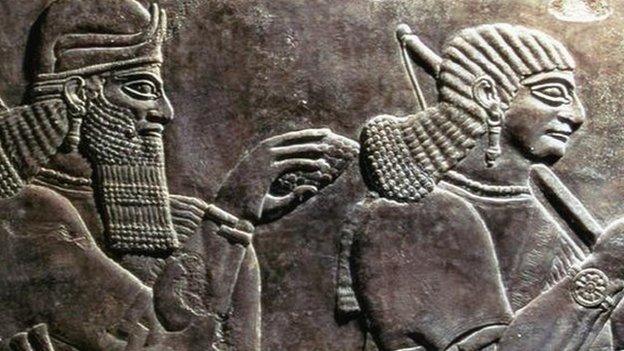

And that experience brings unique insights. Mr Vincent gives the example of the imposing lion statue, which has a design that can only be fully appreciated in three dimensions.

"If you look at that lion's relief, you'll notice that it has five legs. From the side, it has four legs in motion; if you look at it from the front, it's as if the lion is standing still.

"That's part of the art history of Assyrian art. Likewise, if you look closely at the side of the lion's relief you can still see the cuneiform script."

Sadly, we will never know exactly how precise these digital copies are - because the originals are gone. "We don't have all the parameters that we need... to be able to tell you how accurate those models are," Mr Vincent said.

Prof Roger Matthews of Reading University, UK, described the work as "a terrific project", noting that a similar effort was made after the National Museum of Iraq was looted during the 2003 invasion.

"Obviously it would be much better not to have to do this, but it's great that this sort of thing is being done - that people are finding the funding, and the public participation to make it possible," Prof Matthews told BBC News.

This statue of a priest from the ancient city of Hatra dates from the 1st Century AD

He added that it was important to see the Mosul artefacts as part of a larger picture of precious - and threatened - heritage in the region.

"Obviously they ransacked Mosul Museum, destroying many statues and other objects. But they've also blown up the Palace of Ashurnasipal II at Nimrud, which was the source of many of the objects in that museum."

The destruction and looting of active archaeological sites like Nimrud was particularly sad, Prof Matthews, said.

"A site like Nimrud has upstanding buildings that were excavated, but there were also large areas never excavated and which are being illegally looted and interfered with. We just don't know what is being taken from these sites."

Printing the past?

Last week, there were fears that IS would destroy the ancient city of Palmyra. For the moment, this threat appears to have receded, but Mr Vincent and his colleagues in many academic disciplines are fearful of further losses from the physical record of human history.

15 reconstructions have been made so far, after the project received more than 700 photos

Looking beyond Project Mosul, Mr Vincent is anxious that other digital preservation efforts should be undertaken more deliberately and proactively. Once a digital record has been created, it would even be possible to physically re-create precious items using 3D printing, he suggested.

This could prove useful in building replicas not only of destroyed or lost artefacts, but also things that are too fragile to be put on public display - as was the case for the remarkable Chauvet cave paintings, now rebuilt above ground in France.

"3D printing is really proving to be one of the most valuable assets for heritage that we have today. It's a way to bring them back to life and have a tactile experience with them, even if we can't guarantee that they're exactly as the original would have been," Mr Vincent said.

"Whether it is because of conflict or natural disaster, our heritage is such a delicate and valuable resource, the only way that we can really preserve it is to take the steps to make those digital surrogates, so that we can protect the physical reality of that heritage as well."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published17 May 2015

- Published15 May 2015

- Published6 March 2015

- Published6 March 2015

- Published26 February 2015

- Published24 April 2015