DNA confirms cause of 1665 London's Great Plague

- Published

First look at a Great Plague skeleton

DNA testing has for the first time confirmed the identity of the bacteria behind London's Great Plague.

The plague of 1665-1666 was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague in Britain, killing nearly a quarter of London's population.

It's taken a year to confirm initial findings from a suspected Great Plague burial pit during excavation work on the Crossrail site at Liverpool Street.

About 3,500 burials have been uncovered during excavation of the site.

Testing in Germany confirmed the presence of DNA from the Yersinia pestis bacterium - the agent that causes bubonic plague - rather than another pathogen.

Some authors have previously questioned the identity of microbes behind historical outbreaks attributed to plague.

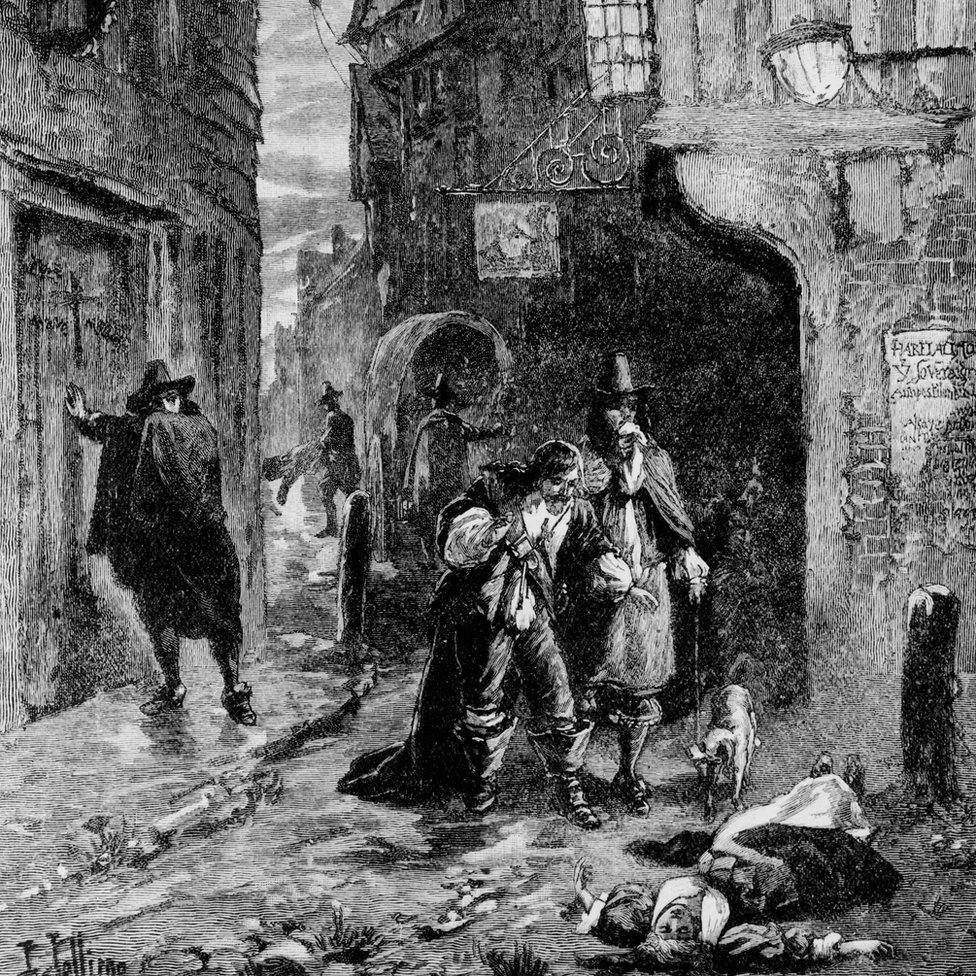

Daniel Defoe's 18th century account of the catastrophic event in A Journal of the Plague Year, external described the gruesome fate of Londoners.

"The plague, as I suppose all distempers do, operated in a different manner on differing constitutions; some were immediately overwhelmed with it, and it came to violent fevers, vomitings, insufferable headaches, pains in the back, and so up to ravings and ragings with those pains," Defoe wrote.

The Great Plague killed about a quarter of the capital's population

"Others with swellings and tumours in the neck or groin, or armpits, which till they could be broke put them into insufferable agonies and torment; while others, as I have observed, were silently infected."

Evidence of the pathogen had eluded archaeologists but seemed tantalisingly close when a suspected mass grave was discovered last year during a Crossrail dig, external at the Bedlam burial ground, also known as the New Churchyard, in East London.

Alison Telfer from Museum of London Archaeology (Mola), external showed me around the area planned for one of the downward escalators going into the future Broadgate ticket hall at Liverpool Street.

"We've found about three-and-a-half thousand burials on this site," she told the BBC's Today programme.

"We've been working here for the last five-and-half-years on and off and we're hoping we'll be able to get positive identification of the plague on a number of the individuals.

More than 3,500 burials have been uncovered at the site

"Because of the position of the skeletons, they'd obviously been laid in coffins & put in very respectfully, nobody was thrown in anywhere in presumably what must have been quite a traumatic event."

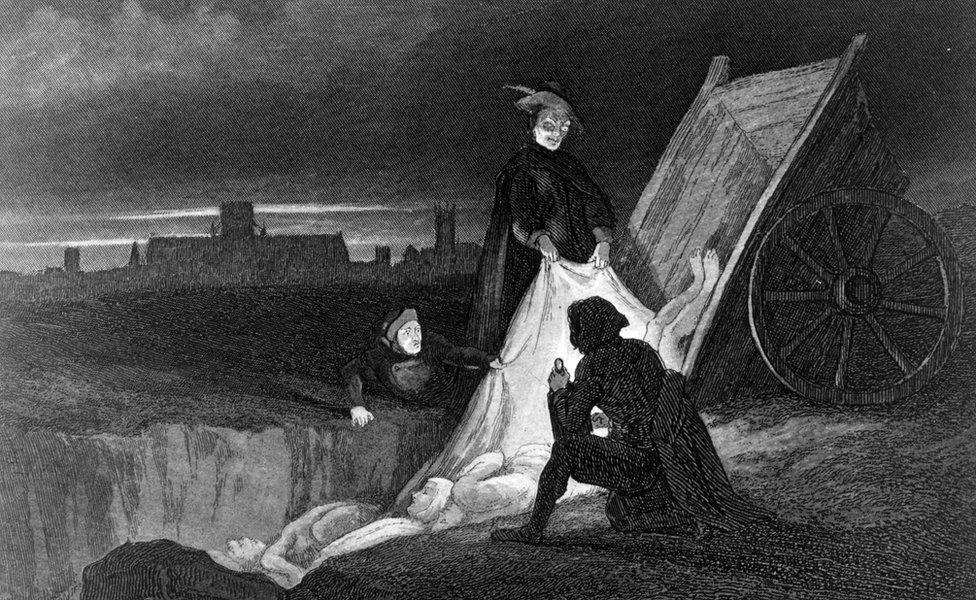

This revelation is somewhat at odds with Daniel Defoe's version of events: "Tis certain they died by heaps and were buried by heaps; that is to say, without account." Panic and disorder only came towards the end of The Great Plague.

Vanessa Harding, professor of London history at Birkbeck, University of London, external, describes the experience of Londoners at the time.

"Not many people who actually get it survive but some do. And it seems to be quite easily transferred from person to person even if we're not sure currently about the agency or way in which this actually happens," Prof Harding said.

Daniel Defoe wrote that plague victims "died by heaps and were buried by heaps"

"But there are also what we might consider public health measures which from their point of view include killing cats and dogs, getting rid of beggars in the streets, trying to cleanse the city in both moral and practical terms. The people who do best are those who get out of London."

The search for the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which causes plague, in a selection of skeletons from the dig continued last year in the osteology department at Mola where all the Liverpool Street finds were stored and examined by Michael Henderson.

"They're carefully boxed, individual elements, legs separately, arms separately, the skulls and the torsos," he explained.

"We excavated in the region of three and a half thousand skeletons, one of the largest archaeologically excavated to this date. A vast data set that can give us really meaningful information."

DNA from the London remains was analysed at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany

The bones are laid out in anatomical order. Teeth are removed and sent for ancient DNA analysis at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, external in Jena, Germany. "The best thing to sample for DNA is the teeth; they're like an isolated time capsule," said Mr Henderson.

In Germany, molecular palaeopathologist Kirsten Bos drilled out the tooth pulp to painstakingly search for the 17th century bacteria, finally obtaining positive results from five of the 20 individuals tested from the burial pit.

"We could clearly find preserved DNA signatures in the DNA extract we made from the pulp chamber and from that we were able to determine that Yersinia pestis was circulating in that individual at the time of death," she said.

"We don't know why the Great Plague of London was the last major outbreak of plague in the UK and whether there were genetic differences in the past, those strains that were circulating in Europe to those circulating today; these are all things we're trying to address by assembling more genetic information from ancient organisms."

A nearby gravestone marks the passing of Mary Godfree, a plague victim

Bos and her team will now continue to sequence the full DNA genome to better understand the evolution and spread of the disease.

There was nothing to identify those found in the mass grave under the Crossrail development but located a short distance away a headstone was found inscribed with the name Mary Godfree who fell victim to the plague. Her interment is recorded in the burial register of St Giles, Cripplegate, on 2 September 1665.

To reassure anyone worried whether plague bacterium was released from the excavation work or scientific analysis, it doesn't survive in the ground.