Survival secret of 'Earth's hardiest animal' revealed

- Published

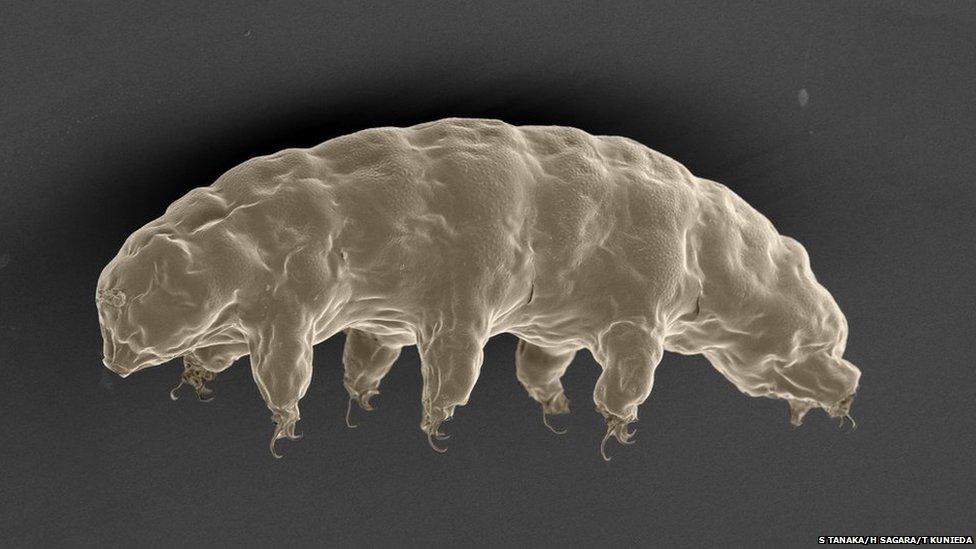

Meet the planet's hardiest animal - the tardigrade - that has just revealed a genetic secret that could help protect human cells.

Researchers have discovered a genetic survival secret of Earth's "hardiest animal".

A gene that scientists identified in these strange, aquatic creatures - called tardigrades - helps them survive boiling, freezing and radiation.

In future, it could be used to protect human cells, the researchers say.

It was already known that tardigrades, also known as water bears, were able to survive by shrivelling up into desiccated balls.

But the University of Tokyo-led team found a protein that protects its DNA - wrapping around it like a blanket.

The tardigrade-specific gene helps the animal resist radiation

The scientists, who published their findings in the journal Nature Communications, external, went on to grow human cells that produced that same protein, and found that it protected those cells too.

This, the scientists suggest, means that genes from these "extremophiles", might one day be used to protect living things from radiation - from X-rays, or as a treatment to prevent damage from the Sun's harmful rays.

Tardigrades are more commonly - and cutely - known as water bears. Scientists had thought that they survived radiation exposure by repairing the damage done to their DNA. But Prof Takekazu Kunieda, of the University of Tokyo, and his colleagues, carried out an eight-year study of a tardigrade genome to pinpoint the source of its remarkable resilience.

Extreme genetics

To identify their secret weapon, researchers scrutinised the genome of one tardigrade species, looking for proteins that were attached to the DNA, and that therefore might have a protective mechanism. They found one that they have called "Dsup" (short for "damage suppressor").

The team studied the tardigrade, Ramazzottius varieornatus

The team then inserted the Dsup gene into human cells' DNA, and exposed those modified cells to X-rays; Dsup-treated cells suffered far less DNA damage.

Prof Mark Blaxter of the University of Edinburgh told BBC News that the study was "groundbreaking".

"This is the first time an individual protein from a tardigrade has been shown to be active in radiation protection.

"[And] radiation is one of the things that's guaranteed to kill you."

By sequencing and examining the genome, this study also appears to resolve a strange genetic controversy about these creatures. Research published in 2015, involving a different tardigrade species, concluded that the creature had "acquired" a portion of its DNA from bacteria through a process called horizontal gene transfer.

That study suggested that some of these beasts' notorious imperviousness had been snipped out of the bacterial genetic code.

This study found no evidence of this gene transfer.

Aquatic space-bears

Tardigrades are microscopic animals commonly known as water bears

In 2007, a European Space Agency satellite carried thousands of tardigrades into the vacuum of space. Named the Tardis - tardigrades in space - project, it revealed that the animals were able not only to survive, but to reproduce upon returning to Earth

There are more than 800 described species of tardigrade, but thousands more are not yet named

Tardigrades live everywhere where there is water, from the soil in your local park to the bottom of the sea to glaciers in Anarctica

To find your own tardigrade, find some moss, add water and squeeze the water out of the moss on to a microscope slip (any light microscope should work). The little animals will come out with the water (tip courtesy of Mark Blaxter).

The tardigrades themselves, though, were far more resistant to X-rays than the human cells that the researchers manipulated. "[So] tardigrades have other tricks up their sleeves, which we have yet to identify," said Prof Matthew Cobb from the University of Manchester.

With further research, scientists think that genes like Dsup could make it safer and easier to store and transport human cells - protecting, for example, delicate human skin grafts from damage. Prof Kunieda and his co-author on the study, Takuma Hashimoto, applied to patent the Dsup gene in 2015.

Prof Cobb added that, in principle, "these genes could even help us bioengineer organisms to survive in extremely hostile environments, such as on the surface of Mars - [perhaps] as part of a terra-forming project to make the planet hospitable for humans".

And scientists with a fascination for tardigrades think this discovery could be the tip of the iceberg.

Prof Blaxter said that tardigrade research could even explain how exactly "radiation damages DNA, and how we might prevent DNA damage from other sources".

Prof Takekazu Kunieda told BBC News that he hoped more researchers would join the "tardigrade community".

"We believe there [are] a lot of treasures there," he added.

- Published15 January 2016

- Published1 June 2016