Norcia earthquake: Why multiple quakes are hitting Italy

- Published

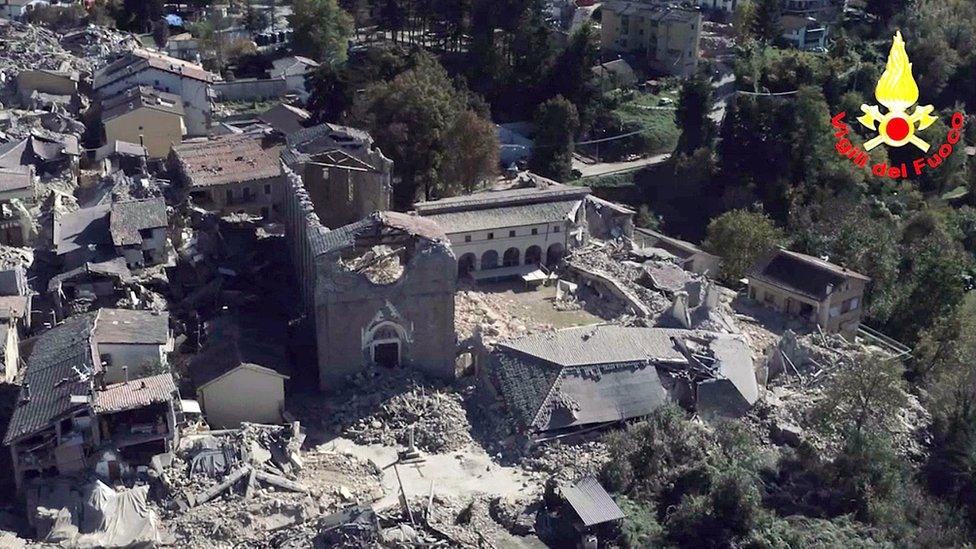

The town of Amatrice has been hit by earthquakes several times in recent months

Sunday's early-morning quake near the town of Norcia is the biggest in Italy since the Magnitude-6.9 Irpinia event in the south of the country in 1980.

Back then, some 2,500 people died and more than 7,000 were injured. Thankfully, we are not expecting loss of life on that scale here.

In part this is because of the strides made in recent years in improving readiness and reaction.

But the fact that the population of central Italy is currently living on such an acute alert status also will have further limited any dreadful consequences.

We have now seen three Magnitude-6 tremors in Italy's Apennines region in just three months.

Quakes 'ever present for Apennines'

The first, in August, was a 6.2. This was followed mid-week by a 6.1. Initial calculations put Sunday's event at 6.6, which in terms of the energy released is actually four times bigger than the quake in August.

Every time there is a rumble, the population's response will be rapid, and saved seconds save lives.

For example, Wednesday's tremor was immediately preceded by a 5.5 foreshock, which would have had many people scurrying for the open streets, putting them safely out of harm's way when the big tremor hit two hours later.

Clustering

Many Apennines residents will of course be asking why there have been so many large quakes in so short a time frame. But this is often how the geology works.

"This is an earthquake sequence; these are related events," explained Dr Richard Walters from Durham University, UK.

"And this triggering of multiple events, sometimes a few days or weeks apart, is well known behaviour."

Look back to 1997 or as far back as 1703, and this clustering in time and space is seen in the same region of Italy.

Scientists are having to move fast, though, to keep on top of what exactly is occurring and to try to join the dots.

The big picture is reasonably well understood. Wider tectonic forces in the Earth's crust have led to the Apennines being pulled apart at a rate of roughly 3mm per year - about a 10th of the speed at which your fingernails grow.

But this stress is then spread across a multitude of different faults that cut through the mountains. And this network is fiendishly complicated.

It does now look as though August's event broke two neighbouring faults, starting on one known as the Laga and then jumping across to one called the Vettore.

The mid-week tremors appear to have further broken the northern end of the Vettore. But both in August and mid-week, it seems only the top portions of the faults have gone, and the big question is whether the deeper segments have now failed in the latest event.

Experts on the ground will be looking for scarps where the soil has split. Dr Laura Gregory from Leeds University, UK, is currently on the scene.

"We're doing monitoring using GPS receivers to look at how the ground is moving in the aftermath of these events.

"We're also looking at the surface expression of the earthquake as well because this can tell you a lot about earthquakes in general and about the earthquakes in this region," she told BBC News.

"It's very important research to do. We still don't really know enough about these earthquakes and we want to get better at forecasting them."

If Sunday's event has broken the lower portions of the faults then surface evidence may be sparse.

Further information will come from the radar satellites that will overfly the Apennines region in the coming days to map the quake zone.

Their pictures will be compared with space images acquired before Sunday's big tremor to see how the rocks have moved.

Europe's Sentinel-1 mission was launched specifically with this kind of work in mind.

Sentinel-1 actually comprises two spacecraft that have already revealed considerable insight into the August quake and its connection with Wednesday's double tremor.

One of the satellites is due to sweep over the Apennines again on Monday.

"We'll then know if it is the deeper extent of both faults that has gone this time," said Dr Walters.

"This would be what we call 'depth segmentation' where the shallow portions break followed by the deeper portions. And it means you can have an earthquake repeating more frequently on the same faults."

Experts will be looking to see how the ground is moving after the quakes

- Published24 August 2016