Asteroid strike made 'instant Himalayas'

- Published

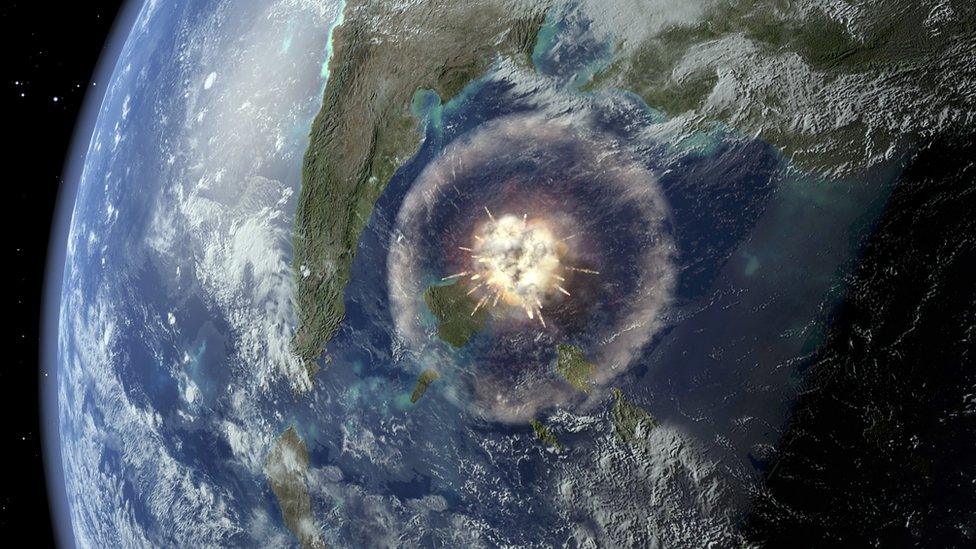

The model animation shows the action in one half of the crater

Scientists say they can now describe in detail how the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs produced its huge crater.

The reconstruction of the event 66 million years ago was made possible by drilling into the remnant bowl and analysing its rocks.

These show how the space impactor made the hard surface of the planet slosh back and forth like a fluid.

At one stage, a mountain higher than Everest was thrown up before collapsing back into a smaller range of peaks.

"And this all happens on the scale of minutes, which is quite amazing," Prof Joanna Morgan, external from Imperial College London, UK, told BBC News.

The researchers report their account in this week's edition of Science Magazine, external.

Their study confirms a very dynamic, very energetic model for crater formation, and will go a long way to explaining the resulting cataclysmic environmental changes.

The debris thrown into the atmosphere likely saw the skies darken and the global climate cool for months, perhaps even years, driving many creatures into extinction, not just the dinosaurs.

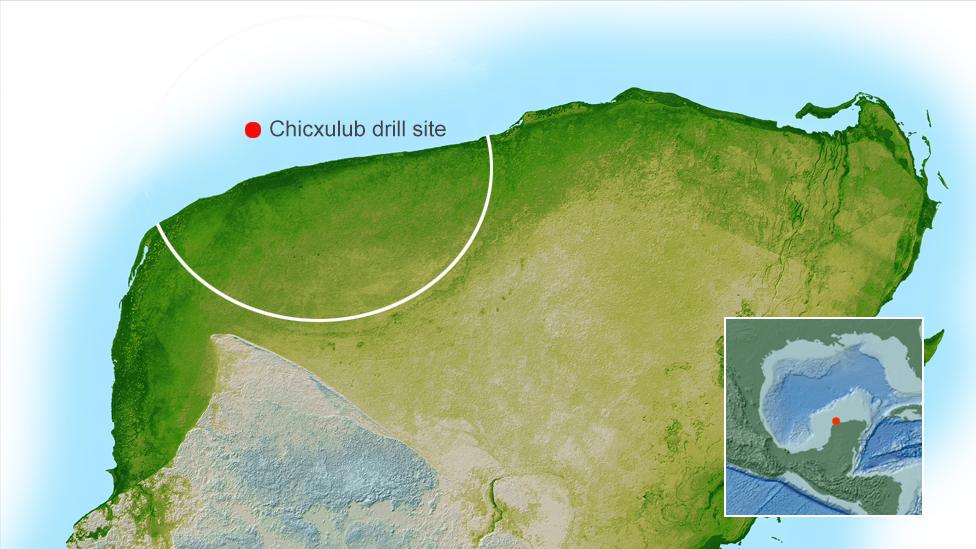

The team spent April to May this year drilling a core through the so-called Chicxulub Crater, now buried under ocean sediments off Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula.

Chicxulub Crater - The impact that changed life on Earth

The outer rim (white arc) of the crater lies under the Yucatan Peninsula itself, but the inner peak ring is best accessed offshore

A 15km-wide object dug a hole in Earth's crust 100km across and 30km deep

This bowl then collapsed, leaving a crater 200km across and a few km deep

The crater's centre rebounded and collapsed again, producing an inner ring

Today, much of the crater is buried offshore, under 600m of sediments

On land, it is covered by limestone, but its rim is traced by an arc of sinkholes

Mexico's famous sinkholes (cenotes) have formed in weakened limestone overlying the crater

The researchers targeted a particular zone in the 200km-wide bowl known as the "peak ring", which - if earlier ideas were correct - should have contained the rocks that moved the greatest distance in the impact. These would have been dense granites lifted from almost 10km down.

And that is precisely what the team found.

"Once we got through the impact melt on top, we recovered pink granite. It was so obvious to the eye - like what you would expect to see in a kitchen countertop," recalled Prof Sean Gulick, external from the University of Texas at Austin, US.

But these were not normal granites, of course. They were deformed and fractured at every scale - visibly in the hand and even down at the level of the rock's individual mineral crystals. Evidence of enormous stress, of having experienced colossal pressures.

The team retrieved many hundreds of metres of rock from the crater

The analysis of the core materials now fits an astonishing narrative.

This describes the roughly 15km-wide stony asteroid instantly punching a cavity in the Earth's surface some 30km deep and 80-100km across.

Unstable, and under the pull of gravity, the sides of this depression promptly started to collapse inwards.

At the same time, the centre of the bowl rebounded, briefly lifting rock higher than the Himalayas, before also falling down to cover the inward-rushing sides of the initial hole.

"If this deep-rebound model is correct (it's called the dynamic collapse model), then our peak ring rocks should be the rocks that have travelled farthest in the impact - first, outwards by kilometres, then up in the air by over 10km, and back down and outwards by another, say, 10km. So their total travel path is something like 30km, and they do that in under 10 minutes," Prof Gulick told the BBC's Science in Action programme.

Imagine a sugar cube dropped into a cup of tea. The drink's liquid first gets out of the way of the cube, moves back in and up, before finally slopping down.

When the asteroid struck the Earth, the rocks it hit also behaved like a fluid.

"These rocks must have lost their strength and cohesion, and very dramatically had their friction reduced," said Prof Morgan. "So, yes, temporarily, they behave like a fluid. It's the only way you can make a crater like this."

Prof Joanna Morgan: "The model we've proven is much more catastrophic"

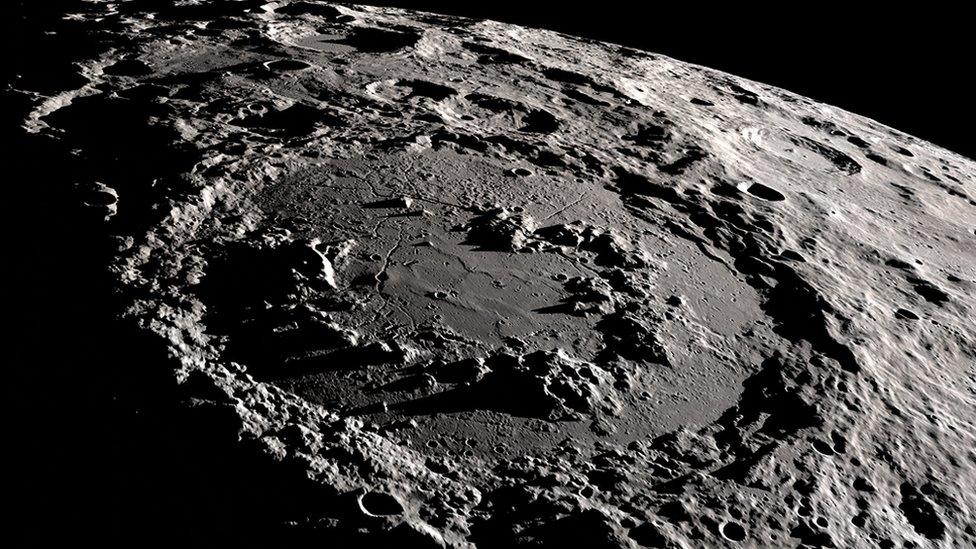

One of the important outcomes of the research is that it provides a useful template also to understand the surfaces of other planets.

All the terrestrial worlds and even Earth's Moon are scarred with craters just like Chicxulub.

And knowing how rocks can move vertically and horizontally in an impact will assist scientists as they attempt to interpret similar crustal features seen elsewhere in the Solar System.

The project to drill into Chicxulub Crater was conducted by the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD), external as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). The expedition was also supported by the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP).

Schrodinger Crater on the Moon looks exactly the same as Chicxulub and would have been made - according to this analysis - in a very similar way

Artwork: The asteroid that made the crater was probably moving at about 20km/s when it hit the Earth

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published11 October 2016

- Published25 May 2016

- Published5 April 2016