Mystery cosmic radio bursts pinpointed

- Published

Artwork: The radio burst studied by the astronomers is the first known example that "repeats"

They're one of the most persistent puzzles in modern astronomy.

As the name suggests, Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) are short-lived - but powerful - pulses of radio waves from the cosmos.

Their brevity, combined with the fact that it's difficult to pinpoint their location, have ensured their origins remain enigmatic.

Outlining their work at a major conference, astronomers say they have now traced the source of one of these bursts to a different galaxy.

It's an important step to finally solving the mystery, which has spawned a variety of different possible explanations, from black holes to extra-terrestrial intelligence.

The first FRB was discovered in 2007, in archived data from the Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia. Astronomers were searching for new examples of magnetised neutron stars called pulsars, but found a new phenomenon - a radio burst from 2001. Since then, 18 FRBs - also referred to as "flashes" or "sizzles" - have been found in total.

The VLA in New Mexico allowed for high resolution imaging of the radio burst

"I don't exaggerate when I say there are more theories for what these could be than there are observed bursts," first author of the new study, Shami Chatterjee, told the BBC's Science in Action programme.

All FRBs were found using single-dish radio telescopes that are unable to narrow down the sources' locations with enough precision to further characterise the flashes.

But Dr Chatterjee, from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and colleagues used a multi-antenna radio telescope called the Karl G Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), external in New Mexico, which had sufficient resolution to precisely determine the location of a flash known as FRB 121102.

Unlike all the others, this FRB - discovered in 2012 - has recurred several times.

"When we reported last year that one of these objects was repeating, that - in one go - knocked out about half of those models, because for this one source, at least, we knew it couldn't be explosive. It had to be something where the engine that produced this survived for the next flash."

In 83 hours of observing time over six months in 2016, the VLA detected nine bursts from FRB 121102.

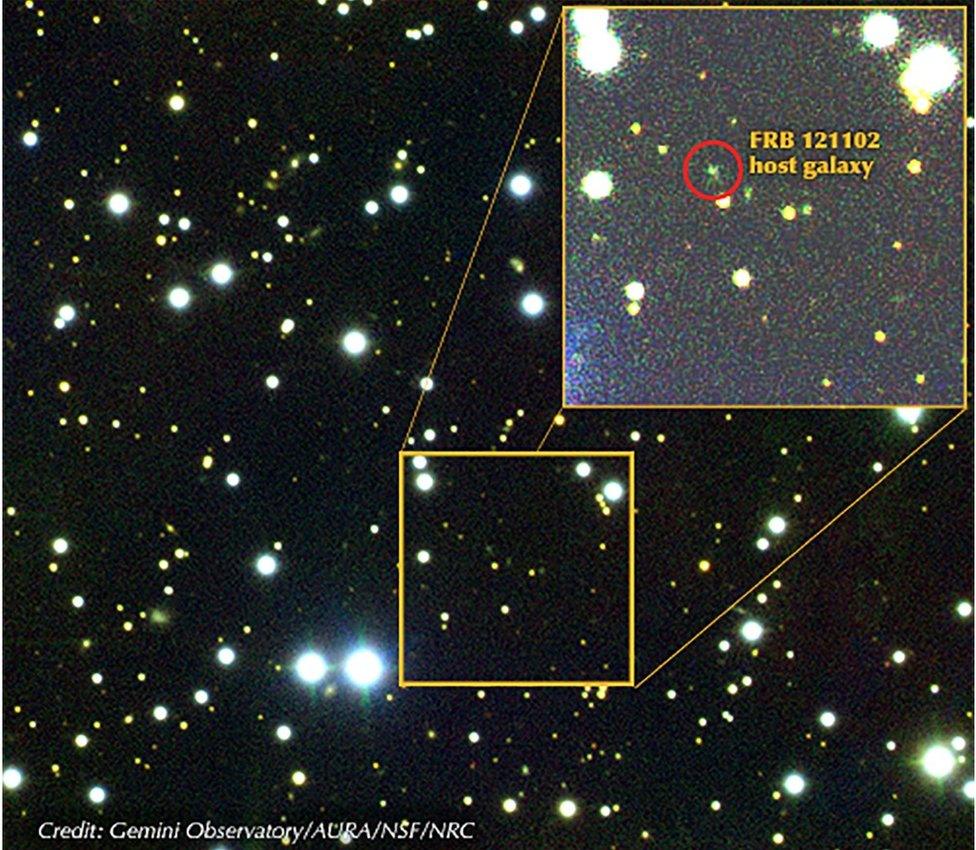

The source of the radio bursts lies more than three billion light-years away

"We now know that this particular burst comes from a dwarf galaxy more than three billion light-years from Earth," said Dr Chatterjee. That's a staggering distance from Earth, underlining just how energetic these flashes are.

"That simple fact is a huge advance in our understanding of these events."

The team has published their findings in Nature journal, external and has outlined them at the 229th American Astronomical Society (AAS), external meeting in Grapevine, Texas.

Since this is the only known repeating burst, it's possible it could represent a completely different phenomenon to other FRBs.

In addition to detecting the bright bursts from FRB 121102, the team's observations also revealed an ongoing, persistent source of weaker radio emission in the same region.

The flashes and the persistent source must be within 100 light-years of each other, and scientists think they are likely to be either the same object or physically associated with one another.

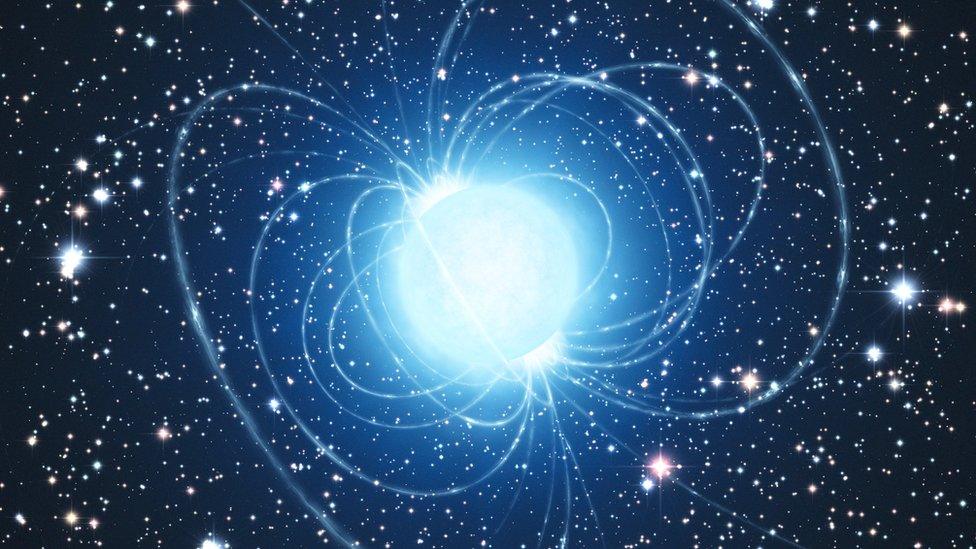

A magnetar - one possible explanation - is a type of neutron star with a particularly powerful magnetic field

"This persistent radio source could be an active galactic nucleus (AGN) at the centre of a galaxy that's feeding (consuming matter from its surroundings), sending out jets, and these sizzles we see are little bits of plasma being vaporised in the jets," said Dr Chatterjee.

"That's not the interpretation we favour. The one we favour is that maybe it's a baby magnetar - a neutron star with a massive magnetic field - and it's got a nebula surrounding it that's powered by the energy being lost by this object. Every once in a while, we're getting a flash from this baby magnetar."

Prof Heino Falcke, who had investigated FRBs, but was not involved in the latest study said that, even without a clear answer, the new findings were a "game changer". But he admitted several features associated with FRB 121102 remained mystifying.

He agreed that some features of the radio source resembled those associated with large black holes. But he said these were typically found only in large galaxies.

He told BBC News: "Why is this spectacular FRB in such a little, very innocent looking galaxy? There are many things coming together which don't make much sense yet.

"Maybe it's a neutron star orbiting a black hole," he said. This might explain the on-off nature of the bursts. But he added: "Why would that produce an FRB where others don't?"

Further research will be needed to clarify the nature of the flashes, and to determine whether all FRBs are caused by the same phenomenon - or have different causes.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external