Defining a true 'pre-industrial' climate period

- Published

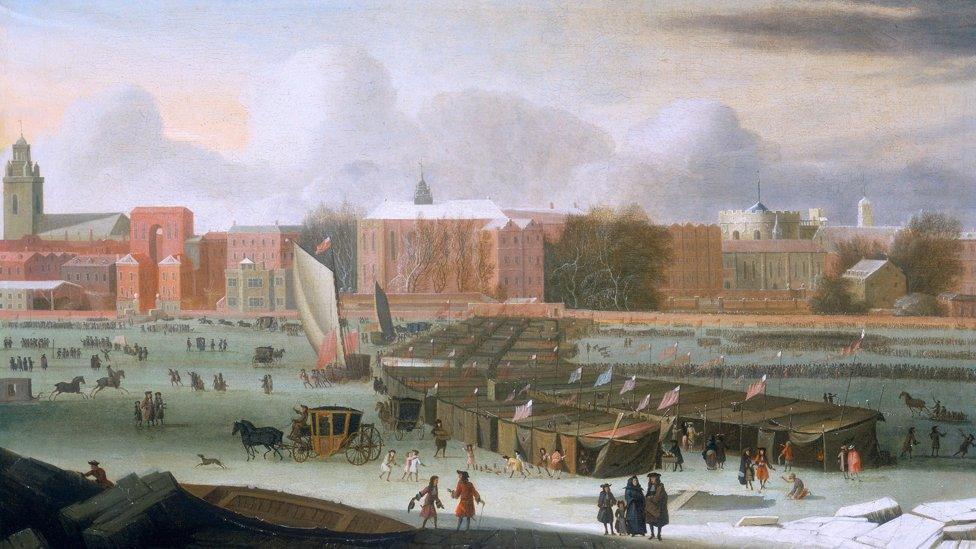

Cool times: A depiction of a 17th Century Frost Fair at Temple Stairs on London's Thames River

Scientists are seeking to define a new baseline from which to measure global temperatures - a time when fossil-fuel burning had yet to change the climate.

At the moment, researchers tend to use the period 1850-1900, and this will often be described as "pre-industrial".

But the reality is that this date range came after industry really got going.

And the influence of humans on the climate was already in play, judging from the ice cores that retain a record of carbon dioxide emissions.

These show a perceptible uptick by 1850-1900; likewise for other greenhouse gases such as methane.

It is these inconsistencies that prompted Ed Hawkins from Reading University and colleagues to look for a more appropriate historical reference period.

And in a new paper published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, external (BAMS), they suggest 1720-1800 might serve as a better "starting line".

On one level, this is a bit of geekery. We know very well what temperatures are doing today, and have a very detailed picture certainly through the 20th Century. That should suffice.

But giving policy-makers a more precise picture of how human-induced global warming has taken hold might better inform the targets they set.

Remember, the Paris agreement sought to maintain global average temperatures to "well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels".

The most recent UK Met Office analysis indicates 2016 was "around 1.1C" above this 1850-1900 baseline.

But if this reference is wrongly set, and possibly now adjusted, it potentially changes how we view the policy targets.

Re-draw the baseline to a warmer or cooler starting point and it will take us either further away or closer to those targets.

Ed Hawkins: Paris didn't define what is meant by 'pre-industrial'

As with all things climate, the issue is a complex one. 1720-1800 has the advantage that it encompasses a time in which fossil fuel use and industrial production was still nascent (James Watt patented his game-changing steam engine condenser in 1769).

And it also avoids some of the big natural impacts that can perturb the climate.

For example, the early 1800s are marked by some truly colossal volcanic eruptions, such as in 1809 (location unknown) and in 1815 (Tambora).

The ash and sulphur emissions from these volcanoes would have depressed global temperatures.

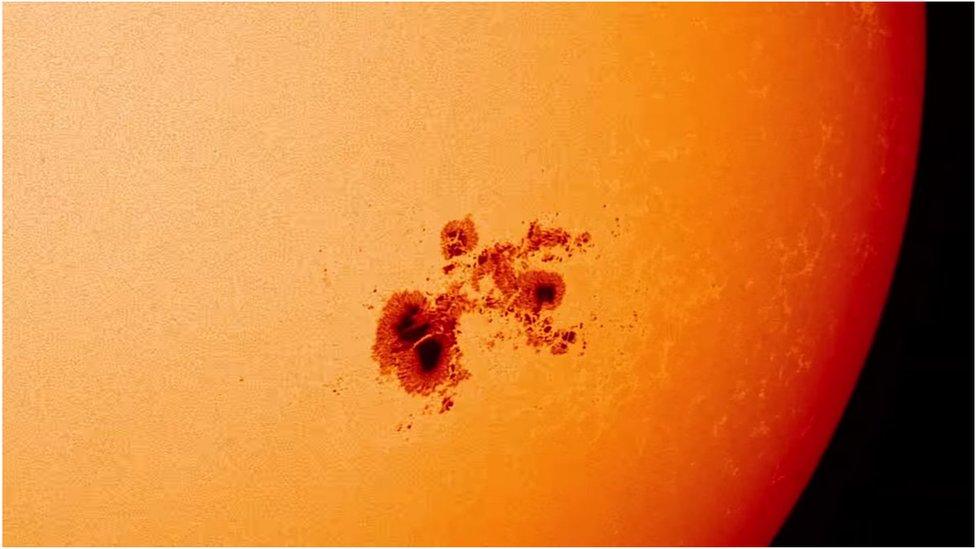

Likewise, if you go back much before 1720, you enter a period when the Sun was particularly inactive; there were remarkably few sunspots for instance (the so-called Maunder Minimum). This too would have damped global temperatures.

Most of the Frost Fairs on the London Thames occurred before 1720.

But that was one city in one part of the world. How do you go about establishing what temperatures were doing across the globe - which is what you need for a proper baseline?

1850-1900 was chosen precisely because there is a reasonable instrument record of climate worldwide.

Go back into 1720-1800 and long-term temperature records become very sparse. There is a very good one for Central England (back to 1659), and a couple on the continent (Netherlands from 1706; and Central Europe from 1760).

Factors that can perturb the climate include solar activity

Dr Hawkins' group used these, together with their understanding of how factors such as greenhouse gases influence the climate, and some modelling, to try to gauge what global temperatures were doing during 1720-1800 - to in essence see if conditions were warmer or cooler than for 1850-1900.

And in their assessment, they were likely cooler.

"We can assess that there has been a certain amount of temperature change from 1850-1900 up to now, and we think that amount is a lower limit on how much temperature (change) there has been since the true pre-industrial period," Dr Hawkins told BBC News.

But the Reading scientist cautions that the uncertainties make it impossible to say precisely how much additional warming there has been if you take 1720-1800 as a new starting point.

"In our paper, we give a broad range because of the uncertainties, but the difference is somewhere between minus 0.05C to plus 0.20C, and we're saying it's likely above zero."

You could narrow the uncertainties somewhat - for example, by rescuing the millions of 18th-and-19th-century temperature observations that currently sit in books around the world but have yet to be collated and digitised. Or you could simply abandon the notion of an 1850-1900 reference altogether and just use a modern comparison.

"This is an option that policy-makers might choose," said Dr Hawkins.

"We obviously have much better observations now and over the past few decades, and so the policy-makers may want to reframe the question. So instead of being, 'Can we keep to two degrees above pre-industrial?', it becomes 'Can we limit ourselves to an amount below, say, the last 20 years or so?'.

"We would be able to monitor progress far more accurately given that - but it is up to the policy-makers to decide whether that's appropriate or not."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter., external