How birds of a feather evolved together

- Published

Citizen scientists have deduced how birds acquired a vast array of beaks over millions of years of evolution.

Bird enthusiasts joined forces with experts to investigate the beak shapes of birds from eagles to pelicans.

The study found there was a burst of evolution of different beak shapes early in the history of birds, soon after other dinosaurs died out.

The great diversity of beaks has long fascinated scientists, including the naturalist Charles Darwin.

While visiting the Galapagos Islands, Darwin discovered several species of finches that varied from island to island, which helped him to develop his theory of natural selection.

Birds have become one of the most successful groups of living things on Earth since the extinction of their dinosaur ancestors 66 million years ago.

"This project has given us key insight into how evolutionary processes play out over millions of years - with major bursts of evolution as new groups emerge, and more fine-scale changes thereafter," said lead researcher Gavin Thomas from the University of Sheffield.

"With the efforts of our volunteers from across the world, the study has given us a unique new data set for the study of bird ecology and evolution."

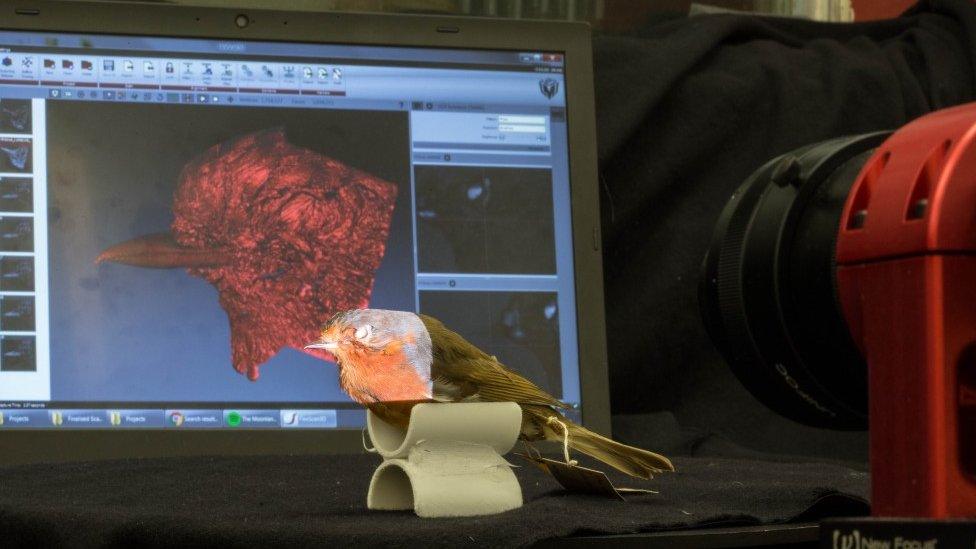

A European robin during scanning

The study revealed a burst of rapid changes in beaks about 70 million years ago, allowing birds to exploit different habitats.

More recently, despite the number of bird species continuing to rise, there has been a slowdown in bird beak diversity.

Thus, the birds that have evolved in the past 30-40 million years have beak shapes quite similar to each other.

There are some exceptions, however. Birds that have evolved in isolation on remote islands such as the Galapagos and the Hawaiian archipelago have continued to evolve rapidly.

Co-researcher Dr Jen Bright, from the University of South Florida, said it was striking how much the speed of evolution changed between different birds.

"It's a really dynamic process, and it means there are still lots of questions left to answer about how birds managed to come up with the range of beak shapes that they have," she said.

The diversity of bird bills

One question of intrigue is why this early dramatic divergence of birds seems to coincide with the period after the extinction of the (non-bird) dinosaurs.

"My personal view is that it's very likely that the extinction of the dinosaurs created the opportunity for birds to diversify into such a wide range of niches which otherwise they might not have been able to do," said Dr Thomas.

"Our results are certainly consistent with that idea."

The study is novel because it relied on the efforts of citizen scientists to help process data compiled from bird specimens in museums.

Taking measurements of beaks from wild birds would have been impossible - not least because of the efforts involved in finding every species of bird. And measuring fossils is problematic because most fossil beaks are not intact.

Researchers used collections of birds at the Natural History Museum in Hertfordshire and the Manchester Museum to make 3D scans of beaks.

Co-researcher Dr Chris Cooney said: "The great diversity of bird beak shapes has long fascinated biologists and naturalists alike, including Darwin himself.

"It is wonderful to be able to use the information stored in natural history collections to shed light on how variation in this important ecological trait evolved."

Tree of life

The digitised data was put into the website Mark my bird, external created by the Digital Humanities Institute at Sheffield.

Members of the public were able to access the data and to help the researchers by marking specific features on birds' beaks.

This process, known as landmarking, involves placing points on features of the beak that are common to all specimens.

Scientists can use the landmarks to mathematically describe the shape of bills in order to compare and test how they differ among species.

The researchers also used information from DNA-based bird trees of life to look at past evolutionary patterns and the processes behind them.

The study, published in the journal Nature, external was carried out on about 2,000 of the 10,000 living bird species.

The scientists are appealing for more volunteers as they still have more birds to study.

Follow Helen on Twitter., external

- Published22 April 2016