Gravity probe exceeds performance goals

- Published

Stefano Vitale: "LISA Pathfinder has been an amazing success"

The long-planned LISA space mission to detect gravitational waves looks as though it will be green lit shortly.

Scientists working on a demonstration of its key measurement technologies say they have just beaten the sensitivity performance that will be required.

The European Space Agency (Esa), which will operate the billion-euro mission, is now expected to "select" the project, perhaps as early as June.

The LISA venture intends to emulate the success of ground-based detectors.

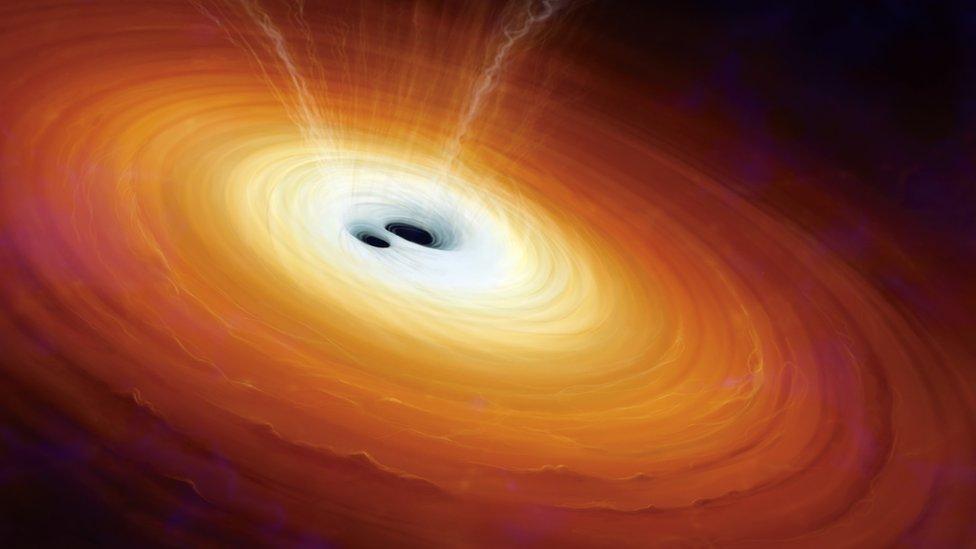

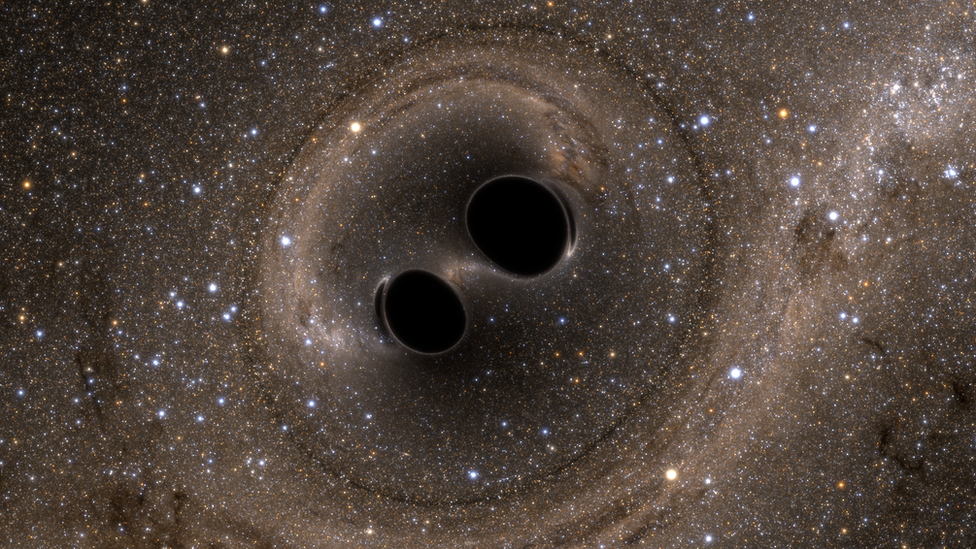

These have already witnessed the warping of space-time that occurs when black holes 10-20 times the mass of the Sun collide about a billion light-years from Earth.

LISA, however, aims to detect the coming together of truly gargantuan black holes, millions of times the mass of the Sun, all the way out to the edge of the observable Universe.

Researchers will use this information to trace the evolution of the cosmos, from its earliest structures to the complex web of galaxies we see around us today.

The performance success of the measurement demonstration was announced here in Boston, external at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

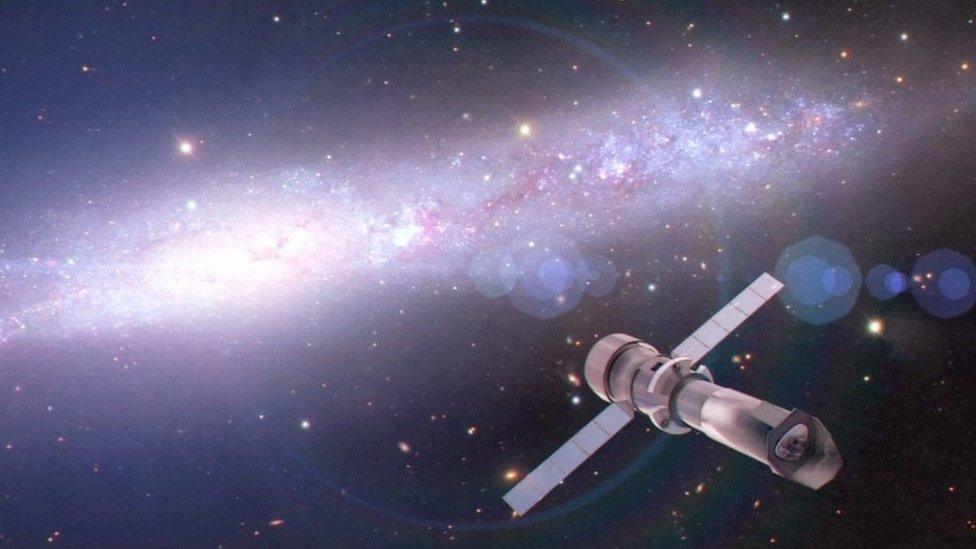

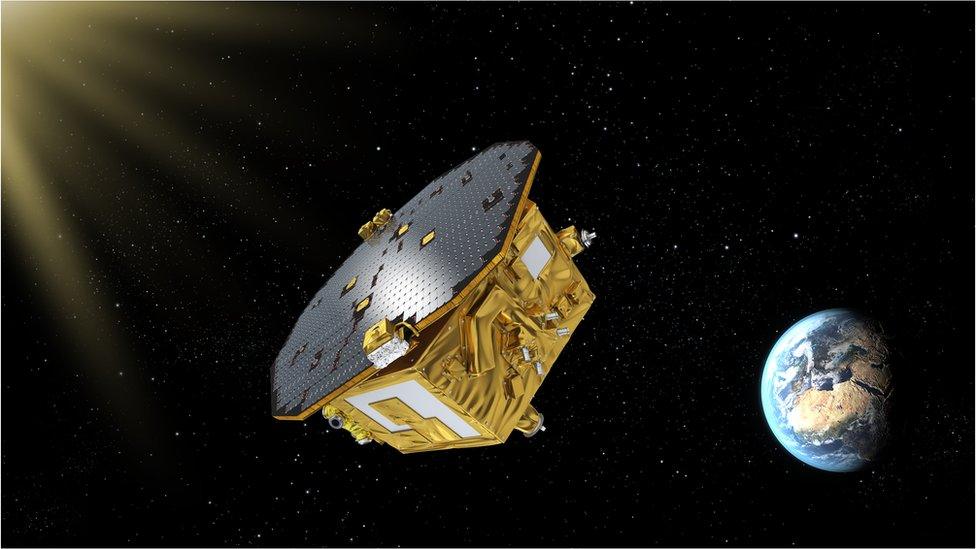

It occurred on Esa's LISA "Pathfinder" (LPF) spacecraft that has been flying for just over a year.

This probe is trialling parts of the laser interferometer that will eventually be used to detect passing gravitational waves.

When Pathfinder's instrumentation was set running it was hoped it would get within a factor of 10 of the sensitivity that would ultimately be needed by the LISA mission, proper.

In the event, LPF not only matched this mark, but went on to exceed it after 12 months of experimentation.

"You can do the full science of LISA just based on what LPF has got. And that's thrilling; it really is beyond our dreams," Prof Stefano Vitale, Pathfinder's principal investigator, told BBC News.

Gravitational waves - Ripples in the fabric of space-time

Gravitational waves are a prediction of the Theory of General Relativity

It took decades to develop the technology to directly detect them

They are ripples in the fabric of space-time produced by violent events

Accelerating masses will produce waves that propagate at the speed of light

Detectable sources ought to include merging black holes and neutron stars

LIGO fires lasers into long, L-shaped tunnels; the waves disturb the light

Detecting the waves opens up the Universe to completely new investigations

The first detection of gravitational waves at the US LIGO laboratories, external in late 2015 has been described as one of the most important physics breakthroughs in decades.

Being able to sense the subtle warping of space-time that occurs as a result of cataclysmic events offers a completely new way to study the Universe, one that does not depend on traditional telescope technology.

Rather than trying to see the light from far-off events, scientists would instead "listen" to the vibrations these events produce in the very fabric of the cosmos.

LIGO achieved its success by discerning the tiny perturbations in laser light that was bounced between super-still mirrors suspended in kilometres' long, vacuum tunnels.

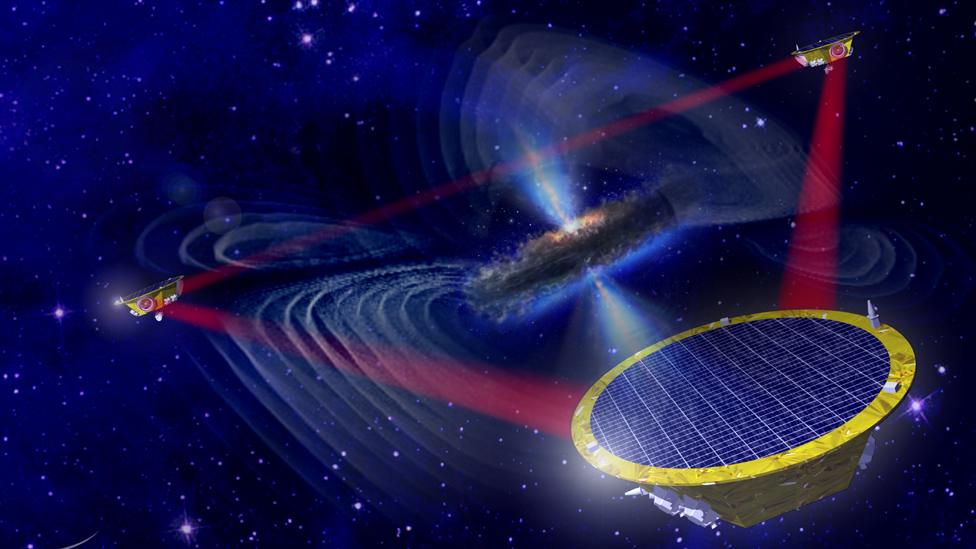

LISA would do something very similar, except its lasers would bounce between free-floating gold-platinum blocks carried on three identical spacecraft separated by 2.5 million km.

Laser science: Lisa Pathfinder's technology demonstration

A cutaway impression of the laser interferometer system inside Lisa Pathfinder

Lisa Pathfinder's payload is a laser interferometer, which measures the behaviour of two free-falling blocks made from a platinum-gold alloy

Placed 38cm apart, these "test masses" are inside cages that are very precisely engineered to insulate them against all disturbing forces

When this super-quiet environment is maintained, the falling blocks will follow a "straight line" that is defined only by gravity

It is under these conditions that a passing gravitational wave would be noticed by ever so slightly changing the separation of the blocks

Lisa Pathfinder has demonstrated sub-femtometre sensitivity, but the satellite cannot itself make a detection of the ripples

To do this, a space-borne observatory would need to reproduce the same performance with blocks positioned 2.5 million km apart

In both cases, the demand is to characterise fantastically small accelerations in the measurement apparatus as it is squeezed and stretched by the passing gravitational waves.

For LISA the projected standard is to characterise movements down below the femto-g level - a millionth of a billionth of the acceleration a falling apple experiences at Earth's surface; and to do that over periods of minutes to hours.

LISA Pathfinder has just succeeded in achieving sub-femto sensitivity over timescales of half a day. Getting stability at the lowest frequencies is very important.

"The lower the frequency to which you go, the bigger are the bodies that generate gravitational waves; the more intense are the gravitational waves; and the more far away are the bodies. So, the lower the frequencies, the deeper into the Universe you go," explained Prof Vitale, who is affiliated to the Italian Institute for Nuclear Physics and University of Trento.

To be clear, LPF cannot itself detect gravitational waves because the "arm length" of the system has been shrunk down from 2.5 million km to just 38 cm - to be able to fit inside a single demonstration spacecraft - but it augurs well for the full system.

Artwork: The LISA concept envisages three spacecraft linked by laser arms that are 2.5 million km in length

Esa recently issued a call for proposals to fly a gravitational science mission in 2034. The BBC understands the agency received only one submission, external - from the LISA Consortium, external.

This is unusual. Normally such calls attract a number of submissions from several groups all with different ideas for a mission. But in this instance, it is maybe not so surprising given that the LISA concept has been investigated for more than two decades.

Prof Karsten Danzmann, co-PI on LPF and the lead proposer of LISA, hopes a way can be found to fly his consortium's three-spacecraft detection system earlier than 2034, perhaps as early as 2029. But that requires sufficient money being available.

"The launch date is only programatically dominated, not technically," Prof Danzmann told BBC News.

"And with all the interest in gravitational waves building up right now, ways will be found to fly almost simultaneously with Athena (Europe's next-generation X-ray telescope slated to launch in 2028).

"This would make perfect sense because we can tell the X-ray guys where to look, because we get the alert of any bright (black hole) merger immediately, and then we can tell them, 'look in the next hour and you'll see an X-ray flash'."

"That would be tremendously exciting to do multi-messenger astronomy with LISA and Athena at the same time."

LISA could be selected as a confirmed project at Esa's Science Programme Committee in June. There would then be a technical review followed by parallel industrial studies to assess the best, most cost-effective way to construct the mission.

Agreement will also be sought with the Americans to bring them onboard. They are likely to contribute about $300-400m of the overall cost in the form of components, such as the lasers that will be fired between LISA's trio of spacecraft.

The LPF demonstration experiments are due to end in May, or June at the latest.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published15 June 2016

- Published7 June 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published27 June 2014