Is there a way to tackle air pollution?

- Published

Logan Eddy helped to test a pollution monitor

The search for solutions to the threat of polluted air is generating ideas that range from the modest to the radical to the bizarre.

A London primary school may issue face-masks to its pupils. The council in Cornwall may take the extreme step of moving people out of houses beside the busiest roads.

Four major cities - Paris, Athens, Mexico City and Madrid - plan to ban all diesels by 2025.

Stuttgart, in Germany, has already decided to block all but the most modern diesels on polluted days.

In India's capital, Delhi, often choked with dangerous air, a jet engine may be deployed in an experimental and desperate attempt to create an updraft to disperse dirty air.

The World Health Organization calculates, external that as many as 92% of the world's population are exposed to dirty air - but that disguises the fact that many different forms of pollution are involved.

For the rural poor, it is fumes from cooking on wood or dung indoors, external.

For shanty-dwellers in booming mega-cities, it is a combination of traffic exhaust, soot and construction dust.

Delhi is one of the most polluted cities in the world

In developed countries, it can be a mix of exhaust gas from vehicles and ammonia carried on the wind from the spraying of industrial-scale farms.

In European cities, where people have been encouraged to buy fuel-efficient diesels to help reduce carbon emissions, the hazard is from the harmful gas nitrogen dioxide and tiny specks of pollution known as particulates.

The first step is to understand exactly where the air is polluted and precisely how individuals are affected - and the results can be extremely revealing.

Personal data

Scientists at the University of Leicester, external are trialling a portable air monitor to gather precise data at a personal scale.

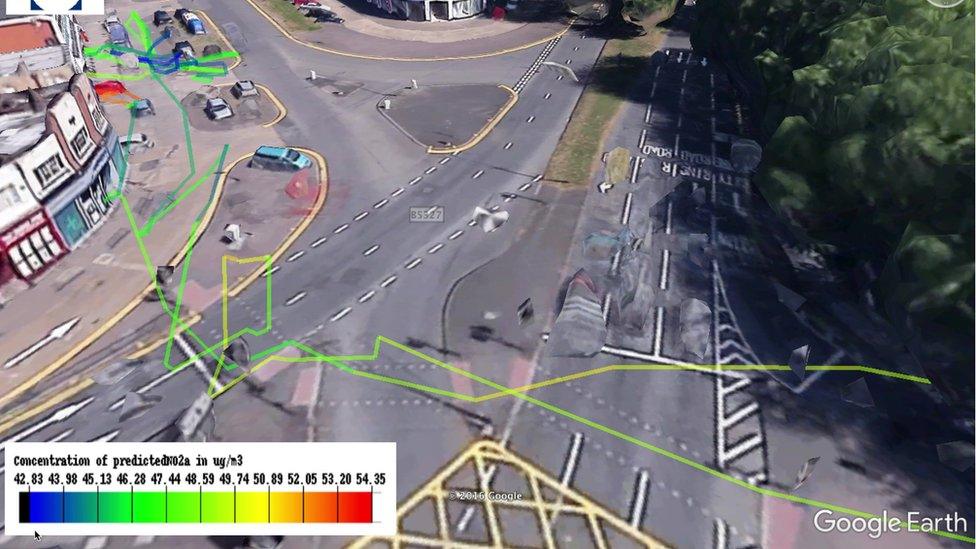

We watched as volunteer, Logan Eddy, 14, carried the device in a specially adapted backpack that recorded details of the air he was exposed to.

Exactly where he walked was then displayed as lines on an electronic map, the colour of those lines conveying how unhealthy the air was at different points.

The monitor gives a readout of pollution during a journey

It was much worse than WHO guidelines where he had waited to cross a busy junction, strikingly cleaner in a side-street but then almost off the scale in a sheltered spot beside an arcade of shops where a car was parked with its engine idling.

Seeing a graphic display of how pollution can vary so dramatically changed Logan's view of air, and his friends adjusted their behaviour immediately.

"The people who found out have stopped waiting right near the buses after school for their friends," he says.

"They've been waiting… further away from the buses.

"It's obviously had an impact on them."

The personal monitor is one of a range of devices being deployed in Leicester to build up a detailed picture of where pollution hotspots form - and when.

In many cases, they can be short-lived, appearing during rush-hours when traffic jams develop.

For Prof Roland Leigh, of Leicester University, understanding precisely where and when vehicles slow to a crawl or stop will help manage the flow of traffic in a way that minimises the impact on the most vulnerable people - the young and the elderly.

"One of the things we can all do is to improve our transport systems so that our congested traffic is not queued up outside of primary schools and old people's homes but instead is queued in other parts of the city where there's going to be less harm," he says.

Cleaning up the engine

But what about tackling one of the main sources of the problem in the first place, the vehicles spewing out the pollutants?

In Europe, under pressure from regulators, the manufacturers have progressively cleaned up their engines over the past few decades - first to trap carbon monoxide and unburned fuel, then particulates and most recently nitrogen dioxide.

Bath is scrutinising vehicular pollutants

The latest European standard, Euro 6, requires vehicles to emit far less pollution than older models, but trust has inevitably been eroded after the car giant VW was caught cheating - using software that activated the emissions controls only during tests.

At Bath University, external, engineers use a "rolling road" and a robotic "driver" to put cars through realistic simulations of how they are normally used, to find out exactly what's released from the exhaust pipe.

They are also working to understand the trade-offs involved in cleaning up an engine.

For example, adding more pollution-trapping devices can add to fuel consumption, which means increased emissions of carbon dioxide, undermining efforts to tackle climate change.

And however good the latest standards, they still leave vast numbers of older vehicles out on the roads.

Hence the idea of a national scrappage scheme, external - to provide incentives to drivers to switch to a cleaner model.

It's attracting growing support from an unlikely coalition including the Federation of Small Business, London First, Greenpeace and the Licensed Taxi Drivers' Association.

The challenge, as ever, is to find the money to make this happen and to agree who should pay - taxpayers through government incentives or the vehicle owners themselves.

Prof Chris Brace, an automotive engineer of Bath University, says; "Whichever way you approach it, you are asking people to spend more in taxation or more to buy new vehicles, and we need to decide whether that's something we're comfortable with as a society."

Some awkward choices lie ahead.

Will the parents of an asthmatic child dig deep in their pockets to switch to a cleaner car?

Will new housing developments include charging points for electric cars?

Will the money saved from a fuel-efficient diesel be seen as worth sacrificing for the sake of better air for everyone?

And bear in mind that these are "First World" questions.

In the rapidly growing cities of Africa, and many parts of Asia, there is hardly any monitoring of pollution at all, let alone political will or money to tackle it.

So I Can Breathe

A week of coverage by BBC News examining possible solutions to the problems caused by air pollution.

- Published2 February 2017

- Published10 December 2016