DNA clues to why woolly mammoth died out

- Published

Breakthroughs in ancient DNA sequencing give a window into the past

The last woolly mammoths to walk the Earth were so wracked with genetic disease that they lost their sense of smell, shunned company, and had a strange shiny coat.

That's the verdict of scientists who have analysed ancient DNA of the extinct animals for mutations.

The studies suggest the last mammoths died out after their DNA became riddled with errors.

The knowledge could inform conservation efforts for living animals.

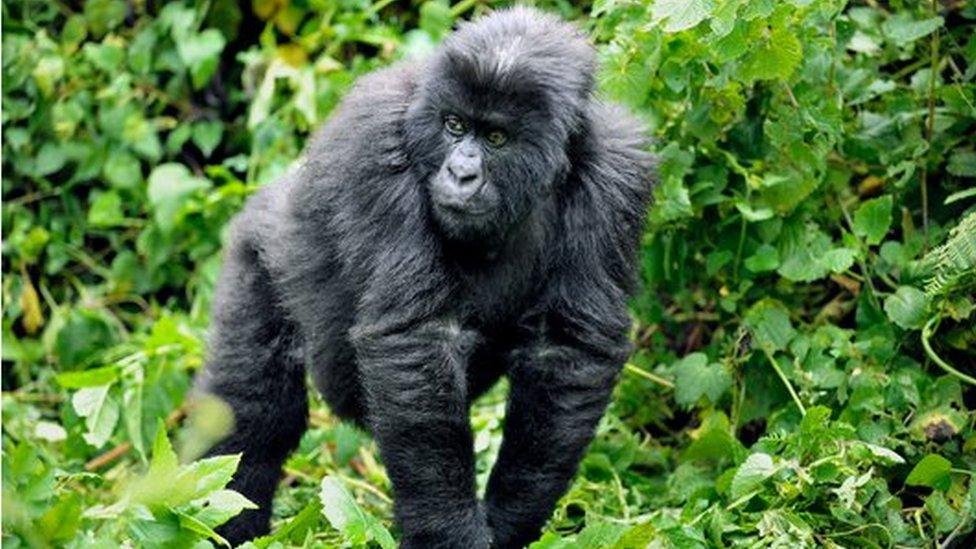

There are fewer than 100 Asiatic cheetahs left in the wild, while the remaining mountain gorilla population is estimated at about 300. The numbers are similar to those of the last woolly mammoths living on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean around 4,000 years ago.

Woolly mammoths died out because of "mutational meltdown", Dr Rebekah Rogers tells The World Tonight

Dr Rebekah Rogers of the University of California, Berkeley, who led the research, said the mammoths' genomes "were falling apart right before they went extinct".

This, she said, was the first case of "genomic meltdown" in a single species.

"You had this last refuge of mammoths after everything has gone extinct on the mainland," she added.

"The mathematical theories that have been developed said that they should accumulate bad mutations because natural selection should become very inefficient."

The researchers analysed genetic mutations found in the ancient DNA of a mammoth from 4,000 years ago. They used the DNA of a mammoth that lived about 45,000 years ago, when populations were much larger, as a comparison.

The woolly mammoth roamed during the last Ice Age and vanished about 4,000 years ago

Woolly mammoths were once common in North America and Siberia. They were driven to extinction by environmental factors and possibly human hunting about 10,000 years ago. Small island populations clung on until about 4,000 years ago.

"There was this huge excess of what looked like bad mutations in the genome of the mammoth from this island," said Dr Rogers.

"We found these bad mutations were accumulating in the mammoth genome right before they went extinct."

Knowledge of the last days of the mammoth could help modern species on the brink of extinction, such as the panda, mountain gorilla and Indian elephant. The lesson from the woolly mammoth is that once numbers drop below a certain level, the population's genetic health may be beyond saving. Genetic testing could be one way to assess whether levels of genetic diversity in a species are enough to give it a chance of survival. A better option is to stop numbers falling too low.

"When you have these small populations for an extended period of time they can go into genomic meltdown, just like what we saw in the mammoth," said Dr Rogers.

"So if you can prevent these organisms ever being threatened or endangered then that will do a lot more to help prevent this type of genomic meltdown compared to if you have a small population and then bring it back up to larger numbers because it will still bear those signatures of this genomic meltdown."

The critically endangered mountain gorilla population is threatened by habitat loss, poaching, disease and war

Scientists think the genetic mutations may have given the last woolly mammoths "silky, shiny satin fur". Mutations may have also led to a loss of olfactory receptors, responsible for the sense of smell, as well as substances in urine involved in social status and attracting a mate.

Love Dalen is professor of evolutionary genetics at the Swedish Museum of Natural History and head of the team of scientists that originally published the DNA sequences of the mammoths.

He said they found "many deletions, big chunks of the genome that are missing, some of which even affected functional genes".

"This is a very novel result," he said. "If this holds up when more mammoth genomes, as well as genomes from other species, are analysed, it will have very important implications for conservation biology."

The research is published in the journal, PLOS Genetics, external.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published3 March 2017

- Published2 August 2016