James Webb telescope: Hubble successor set for yet more tests

- Published

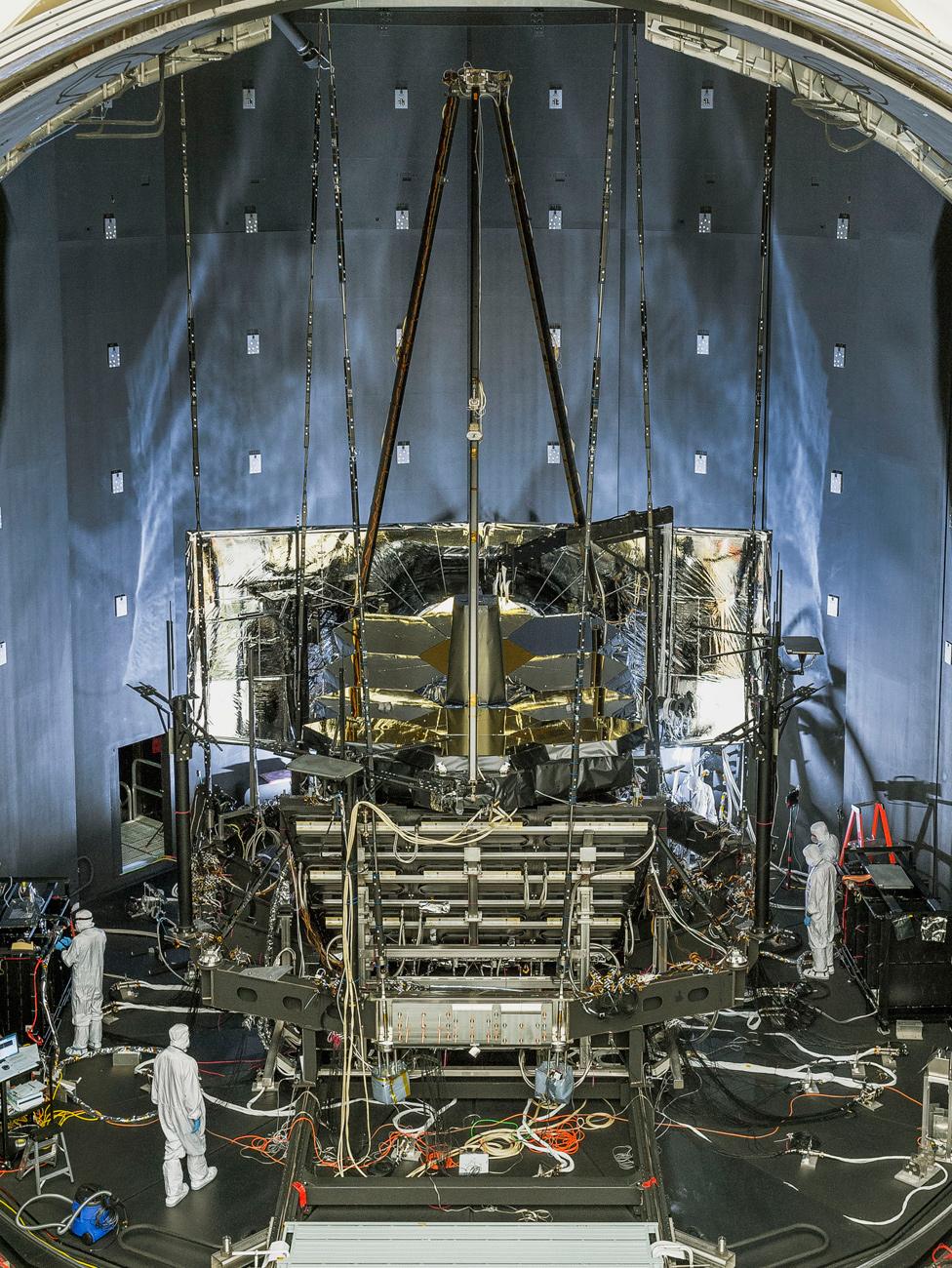

JWST has just emerged from vibration and acoustic investigations

Engineers are getting ready to box up the James Webb Space Telescope and send it to Houston, Texas.

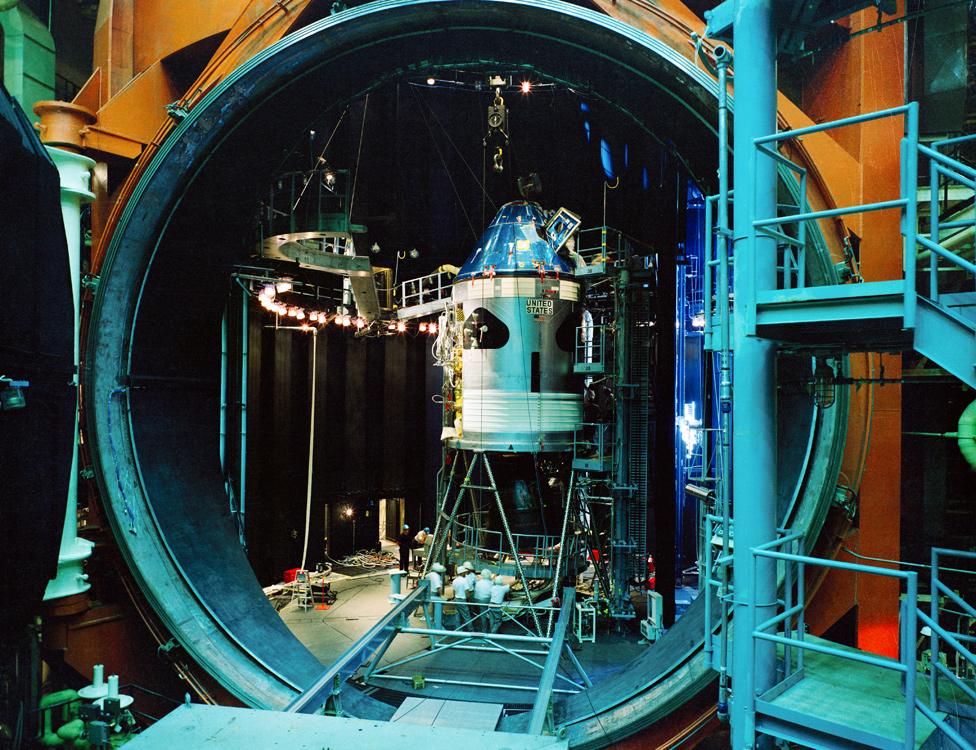

The successor to Hubble, due for launch in 2018, is going to be put inside the giant thermal vacuum chamber where they tested the Apollo spaceships.

For 90 days, JWST will get a thorough check-up in the same airless, frigid conditions that will have to be endured when it eventually gets into orbit.

The telescope's aim will be to find the first stars to shine in the Universe.

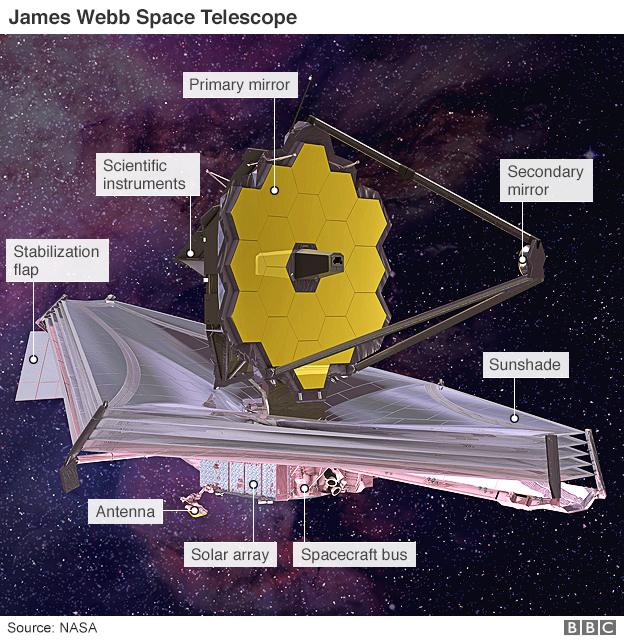

To achieve this goal, the observatory is being given an enormous mirror and instruments that are tuned to detect some of faintest objects on the sky.

More than two decades in development, JWST is currently passing through the most critical phases on its construction timeline.

Any major technical hiccups now would seriously derail its launch readiness.

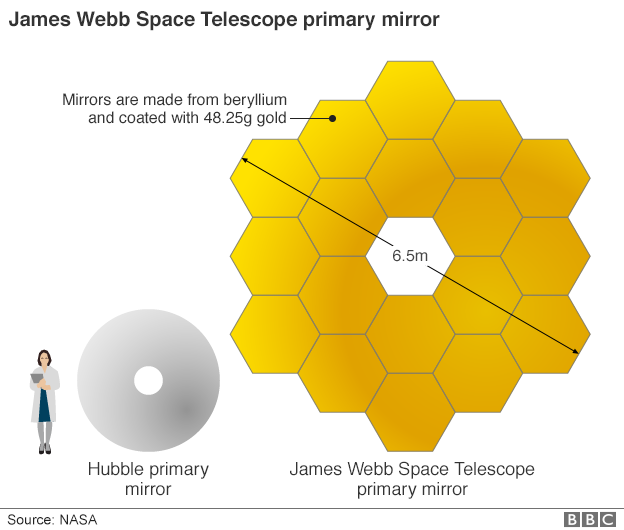

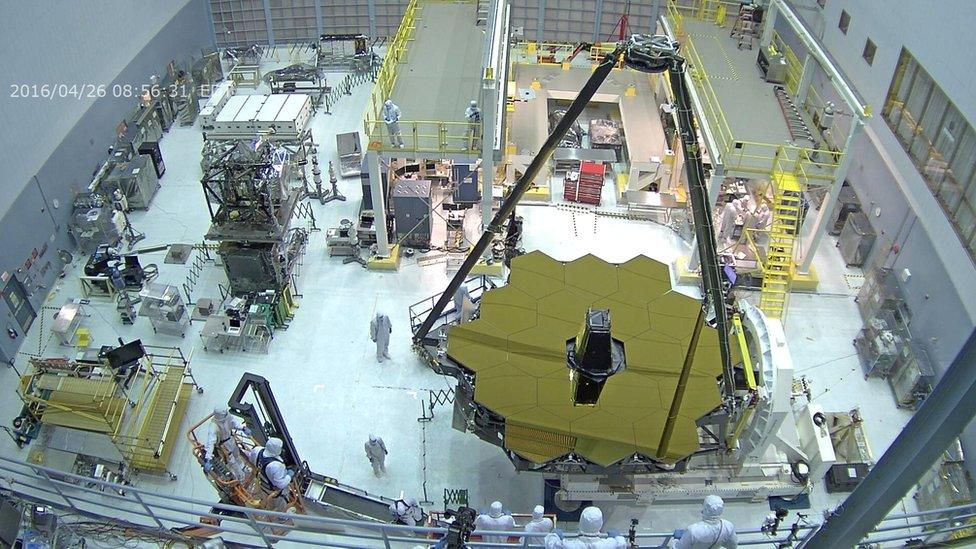

The past year has seen the assembly of the main telescope structure, with its 18 beryllium-gold mirror segments, at the US space agency's (Nasa) Goddard centre in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Attached to this structure are Webb's four observing instruments, which sit inside a cage on the rear of the big reflector.

The telescope structure was assembled at the Goddard Space Flight Center

The whole edifice has just gone through vibration and acoustic testing at Goddard. This has simulated the shaking and the roar of the carrier rocket. This will be an Ariane 5 provided by project partner, the European Space Agency.

One vibration run had to be stopped early when unexpected accelerations were detected in the region of the telescope's secondary mirror, but the analysis concluded it was not an issue of significant concern. So far, so good.

Now, JWST must fly to Nasa's Johnson centre at the end of April, or perhaps the beginning of May.

There, it will enter the famous Chamber A. This is the largest testing facility of its kind in the world, and the only one capable of housing an orbiting telescope on JWST's scale.

Chamber A is the facility that ran the rule over Apollo hardware

Engineers want to know that Webb's mirrors and instruments will function in unison when they are sitting out in space.

The chamber will provide important evidence of that by going super-cold (it can go as low as minus 260 Celsius).

An artificial light source shone on to Webb will ensure everything lines up as it should.

"When we are at temperature, we will unfold the mirrors and move them," explained JWST instrument systems engineer Begoña Vila.

"On orbit, not only do they have to unfold, you have also to confirm the focus for the different instruments.

"If you think about it, with those 18 segments we start with 18 different images of a star, and so we have to move all those images until we have a single one and it is in focus. It's that process that we have to practise," she told BBC News.

This work should complete in the autumn, but there will be no hiatus in the schedule. Webb will immediately go to Los Angeles to the aerospace company Northrop Grumman.

It is in California where the final elements of the observatory are being put together.

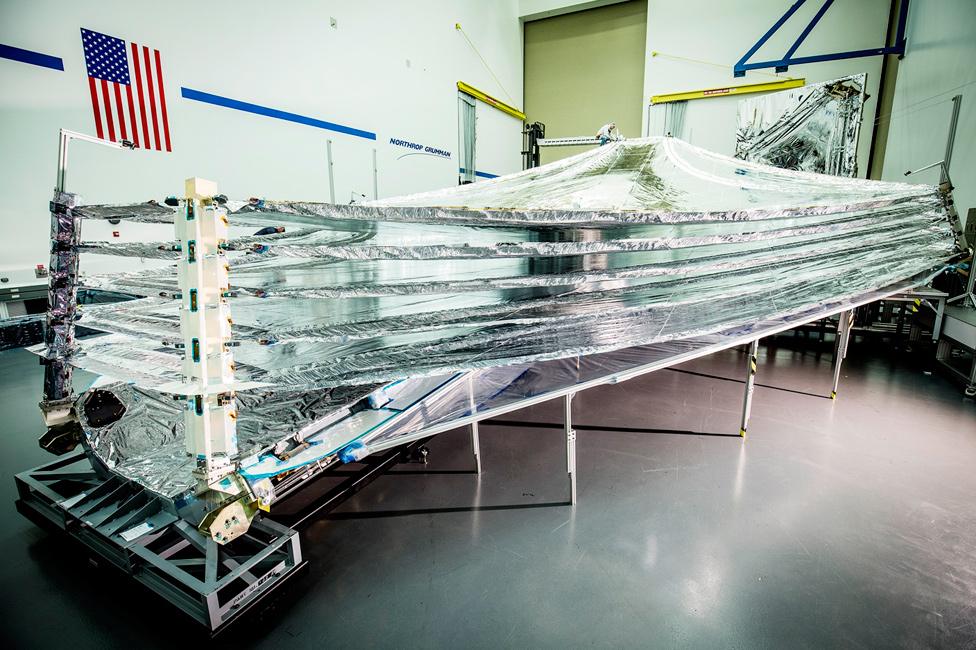

These are the satellite bus, which incorporates the computers, the power and propulsion systems, etc, needed to control Webb in space; and a tennis-court-sized sunshield.

JWST will look at the cosmos in infrared light and so needs to be shaded from the glare and heat of the Sun.

Bus and shield are in their end stages of assembly. Some final components still have to be attached, such as a boom that will deploy the shield once in space, but Northrop Grumman anticipates everything being in position to receive the telescope structure and instruments when they turn up for final integration.

The shield and satellite bus will be attached to the telescope structure in Los Angeles

The finished observatory's journey from LA to the Ariane launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana, will be made by boat.

This is earmarked to begin about six months before the currently slated November 2018 lift-off.

"At this point we are in good shape," confirmed Eric Smith, JWST's programme director and programme scientist.

"We have about five months of scheduled reserve. That's more than is typical for a programme at Nasa but we recognise that this programme is very large and so we know we need to have a little more.

"It's amazing how fast everything is going at this point. But I keep telling people this is the part where you're going to keep finding problems because even though you've tested things all the way up, when you finally put it together some of those things behave just a little bit differently to how you were expecting.

"It's exciting but, boy, it's moving fast," he told BBC News.

Engineers have already simulated the chamber testing with a model telescope

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published3 November 2016

- Published26 April 2016

- Published26 January 2016

- Published23 April 2015

- Published31 July 2015