Gunfire audio opens new front in crime-fighting

- Published

Pioneering work to extract detailed information from audio recordings of gunshots could give forensic case officers new avenues for solving murder cases.

The hustle and bustle of a city going about its business is broken by the crack of gunshots, sending bystanders running and screaming. In the aftermath one man lies dead and another badly injured.

Further down the street, four security cameras outside a local resident's home picked up the sound of the exchange of fire between the two men, but no images of what happened.

Eyewitnesses reported seeing the pair standing just a few metres apart firing handguns at each other, but it is unclear which of the two perpetrators shot first.

In an attempt to unravel what happened, local police called Robert Maher, a professor in electrical and computer engineering at Montana State University.

Using audio captured by the microphones on the security cameras, he was able to reconstruct the incident shot-by-shot to reveal where each of the men were standing and who fired first.

Prof Maher is one of a small group of acoustics experts working to establish a new field of forensics that examines the sound of gunshots recorded on camera footage or by phones.

"Nowadays it is not uncommon for someone with a cell phone to be making a video at the time of a gunfire incident," he explains. "The most common types of recordings are from dashboard cameras or vest-mounted cameras carried by law enforcement officers.

"Also common are recordings from an emergency telephone call centres where the calls are being recorded and the caller's phone picks up a gunshot sound. In some cases there are private surveillance systems at homes and businesses that include audio recordings."

Different guns sound similar to the human ear, but software can tell the difference

Gunshots make a distinctive sound that makes them easy to distinguish from other commonly mistaken noises such as a car backfiring or fireworks.

A firearm produces an abrupt blast of intense noise from the muzzle that lasts just one or two millionths of a second before disappearing again. High-powered rifles also produce an additional sonic boom as the bullet passes through the sound barrier before the sound of the muzzle blast is detected.

Most of us spend our lives surrounded by devices capable of capturing these sounds inadvertently if a crime occurs nearby. Professor Maher's aim is to extract details from these recordings that might help police piece together a crime.

Together with his colleagues, he has been compiling a database of firearm sounds in a project funded by US National Institute of Justice. They are firing an array of rifles, shotguns, semiautomatic pistols and revolvers beside an array of 12 microphones arranged in a semicircle.

Each of the guns appear broadly similar to human ears when fired on an open range, but using software to analyse the sound waves picked up by the microphones, they have found it is possible to distinguish different types of weapon.

"We observe differences between pistols with differing calibre and barrel length for example," says Professor Maher. "Revolvers differ from pistols because sound can emanate from the gap between the revolver cylinder and the gun barrel, causing two sound sources that can be detected at certain angles."

His analysis has also revealed other details can be gleaned from recordings of gunfire.

The shape of the sound wave produced by a gunshot, for example, is different depending on which way the weapon is pointing. If the microphone is off to one side of the shooter, the split second burst of noise can different compared to when it is in front of or behind the gun.

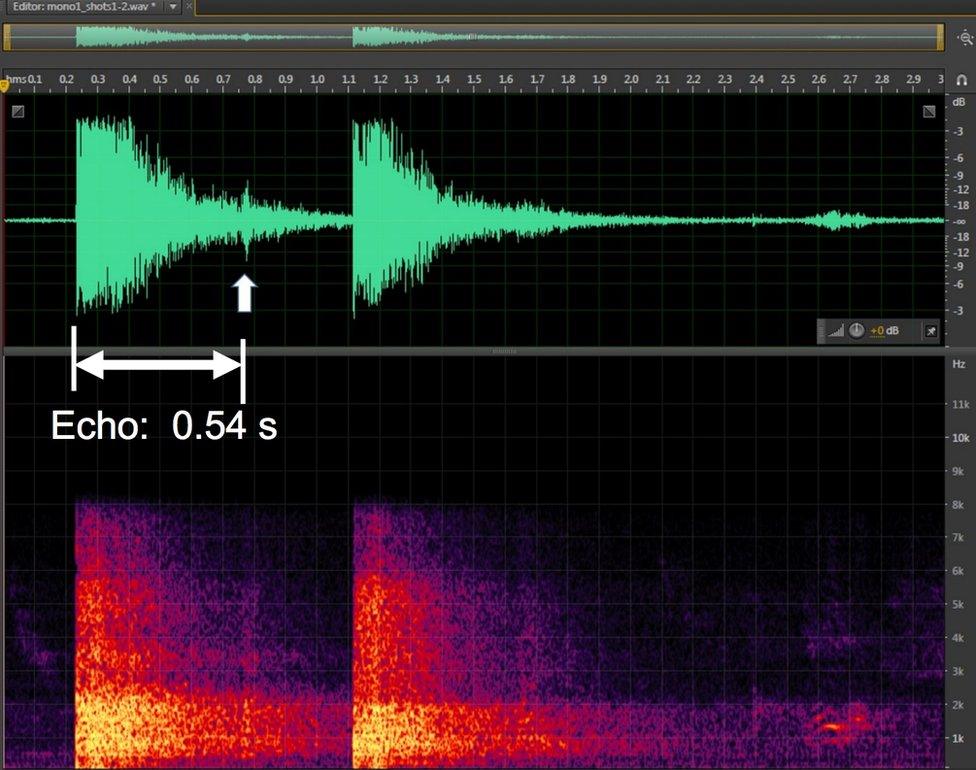

Researchers can extract information from audio recordings of an incident - this shows a double gunshot

They have also found it is possible to pick up distinct echoes as the initial sound produced by a gunshot reverberates off nearby buildings, parked cars, trees and walls. After the initial blast, other smaller blips in the sound wave can be seen within a fraction of a second of the shot.

By calculating the time it takes for sound to travel to and from an obstacle, it is possible to calculate how far a shooter was away from it. It can even reveal if a shooter was firing from an elevated position from the muzzle blast reflecting off the ground.

"This means the orientation and location of shooters in some circumstances can be determined," according to Prof Maher, who revealed some of his findings to a symposium organised by the National Institute of Justice in New Orleans last month.

"In situations where more than one recording of the shooting scene is available, such as where two or more patrol cars equipped with dashboard audio or video recorders are present at an incident, the position of the vehicles can sometimes help triangulate the sounds."

Microphone network

It is a similar concept to the one used by companies like Raytheon, which produces sniper locators for the military that use the sound of a gunshot to locate the shooter. An array of microphones can be mounted on buildings, vehicles or helicopters to help spot shots.

Another firm, Shotspotter, uses a network of microphones across 90 cities in the US to help law enforcement detect gunshots.

The difference with these systems is that they detect gunfire in real time, while Professor Maher is trying piece together what happened days, weeks and even months after a shooting.

In the case described at the start of this article - a real shooting that occurred recently in Cincinnati, Ohio - the injured man claimed he had shot the other man dead in self defence after he was fired at first.

Military systems like Boomerang use gunshot sounds to pinpoint the locations of snipers

With the two gunshots occurring less than a second apart, it was impossible for witnesses to definitely say which of the shooters had fired first.

Using the security camera recordings of a local home owner living further down the street, however, Professor Maher was able to reveal two distinct gunshots in the audio.

Just a few milliseconds after the first gunshot, a distinct second blip appeared in the sound wave, just moments before the second shot was fired.

This blip was the echo of the first gunshot bouncing off a large building at a T-junction around 90 metres to the north. The echo from the second gunshot was far harder to spot in the sound-waves produced.

According to Professor Maher, this suggests the first shooter to fire their gun was the one pointing it to the north - the same man who claimed he had been firing in self-defence.

Professor Maher hopes the growing amount of technology capable of recording audio will make such analysis even easier in the future. The microphones on many older consumer devices are not designed to handle the abrupt, loud sounds of gunshots and it can overload them

But as more homes become equipped with home security cameras and "always-on" smart assistants like Amazon's Echo and Google Home, it may be possible to capture better audio of events.

It is something that other forensics experts believe could have a growing role in the future.

Mike Brookes, a reader in communications and signal processing at Imperial College London, said: ""The sort of question that such recordings can help with are in sorting out the timing and sequence of events that took place and in establishing the position from which a gun was fired."