Antarctica's troublesome 'hairdryer winds'

- Published

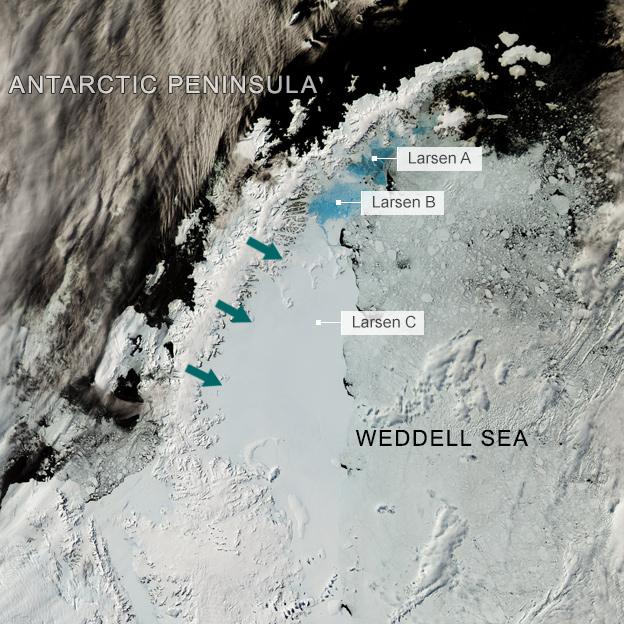

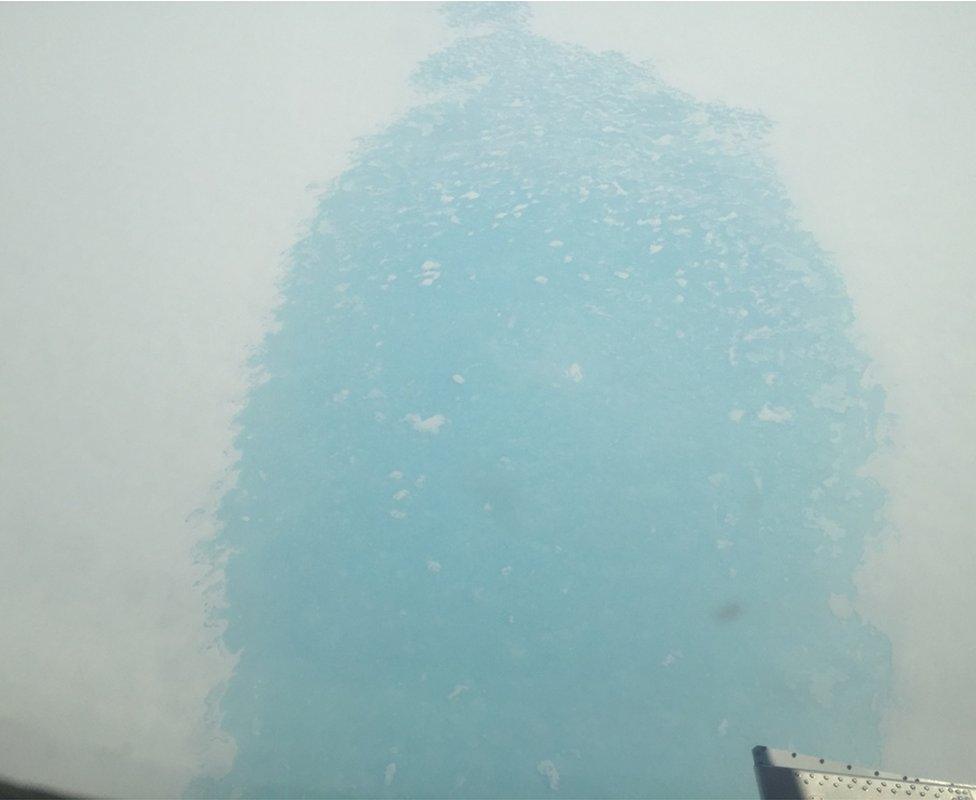

Melt ponds on Larsen C recently photographed from a British Antarctic Survey plane

It's an ill wind that blows no good - at least not for the ice shelves on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

A new study has found an atmospheric melting phenomenon in the region to be far more prevalent than anyone had realised.

This is the foehn winds that drop over the big mountains of the peninsula, raising the temperature of the air on the leeward side well above freezing.

"The best way to consider these winds is how they translate to German now, which is 'hairdryer'," explained Jenny Turton from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"So, they're warm and they're dry and they're downslope. If you take the spring, the air over the ice shelf is usually minus 14 but during the foehn winds it’s above freezing.”

Jenny Turton: "The warm, dry air descends and spreads out across the ice shelf"

The effect on the ice that pushes east from the Peninsula out over the Weddell Sea is clear. It produces great ponds of brilliant blue melt water at the surface.

Such warm, downslope winds are well known across the Earth, of course; and they all have a local name.

The chinook winds, for example, that drop over the Rockies and Cascades in North America are the exact same thing.

Foehn is just the title they garnered originally in Europe's Alps. And while their presence on the White Continent has also long been recognised, the BAS study is really the first effort to try to quantify their behaviour.

Examining data from 2009 to 2012, Turton and colleagues identified over 200 foehn episodes a year.

That makes them more frequent than anyone had thought previously. And the range is broader, too, with occurrences being recorded much further south on the Peninsula.

This all means their melting influence on the eastern shelf ice has very likely been underestimated.

"In summer, we expect some melt, around 2mm per day. But in spring we’re having an equal amount of melt as we are in summer during the foehn winds," Ms Turton told BBC News.

"That's significant because it’s making the melt onset earlier. We kind of expect melt in January/February time; but we’re also seeing it sometimes in September/October, in particularly frequent foehn wind conditions."

Is the Larsen C Ice Shelf being conditioned for a break-up?

The warming effect of the foehn winds (green arrows) is felt at least 130km across the ice shelf

The dominant winds blowing in the Antarctic Peninsula region are westerlies

As their air parcels rise over the mountains, they cool and lose their moisture

The descending air parcels (foehn wind) on the other side are therefore dry

Leeward air is also 5-10 degrees warmer than the equivalent windward altitude

Turton presented the foehn research at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna.

It is timely work because there is considerable interest currently in the status of the Larsen C Ice Shelf - a floating projection from the Peninsula that is the size of Wales.

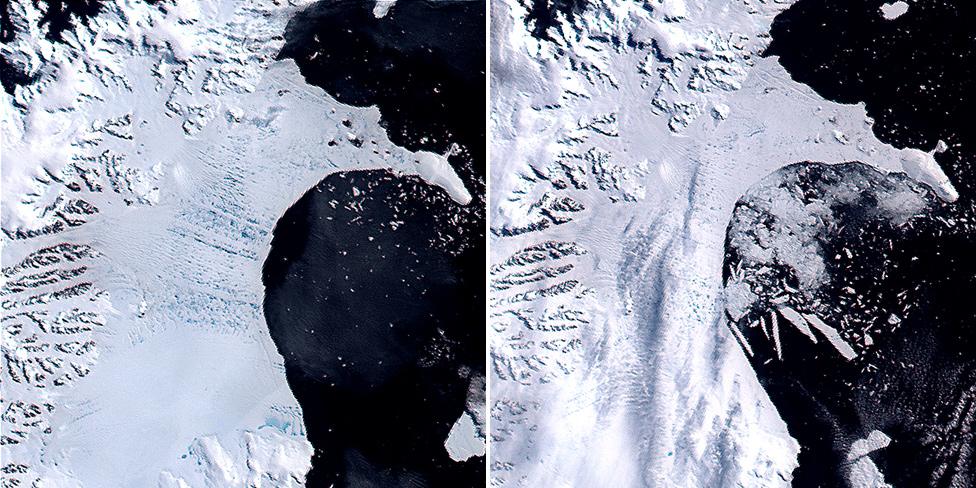

Scientists are wondering if this shelf will follow the demise of its siblings, Larsen A and Larsen B, further to the north.

These collapsed in 1995 and 2002, respectively; Larson B doing so in spectacular style.

Larsen B was covered in thousands of melt pools before shattering in 2002

Larsen C shares some similarities - notably, the presence of those summer melt pools.

This liquid water is problematic because of the way it can seep into crevasses and help to open them up.

The water pushes down on the fissures, driving them through to the base of the shelf in a process known as hydrofracturing. They weaken the shelf.

"The thing about Larsen B though was that it was covered in them," recalled Prof Bernd Kulessa from Swansea University.

"By the time the shelf reached a really weak state, there were literally thousands of ponds. On Larsen C, the ponds are still very much focussed in the inlets (close to the mountains). There are few ponds on the shelf itself and so it is not quite as pre-conditioned."

Meltwater can push down on crevasses, driving them through the shelf

Drawing a lot of attention at the moment is the big iceberg calving event occurring on Larsen C. A mass of ice some 5,000 sq km in area is about to break away.

When the monster berg does detach, it could change the way stress is configured and managed by the remaining shelf structure.

It is interesting to note that the collapses of Larsen A and B were also preceded by major calvings. But these are not swift processes. They do not happen the day after tomorrow; they can take very many years to complete.

Aerial video of the Larsen C ice crack obtained by the British Antarctic Survey

Presently, the putative Larsen C berg is hanging on to the shelf by a 20km stretch of ice. And the crack that will set it free has actually slowed its pace of late.

"It's entered a suture zone which is soft - softer because the ice is warmer and has more water content," Swansea's Prof Adrian Luckman told BBC News.

"As a result the crack cannot propagate as fast as it has done through the colder ice. So, it will be stuck in this suture zone for some time to come. However, where we're measuring the rift width, which is at the point where it broke through the first suture zone it came across - it continues to open by about a metre a day."

In total, that's a gap of more than 450m.

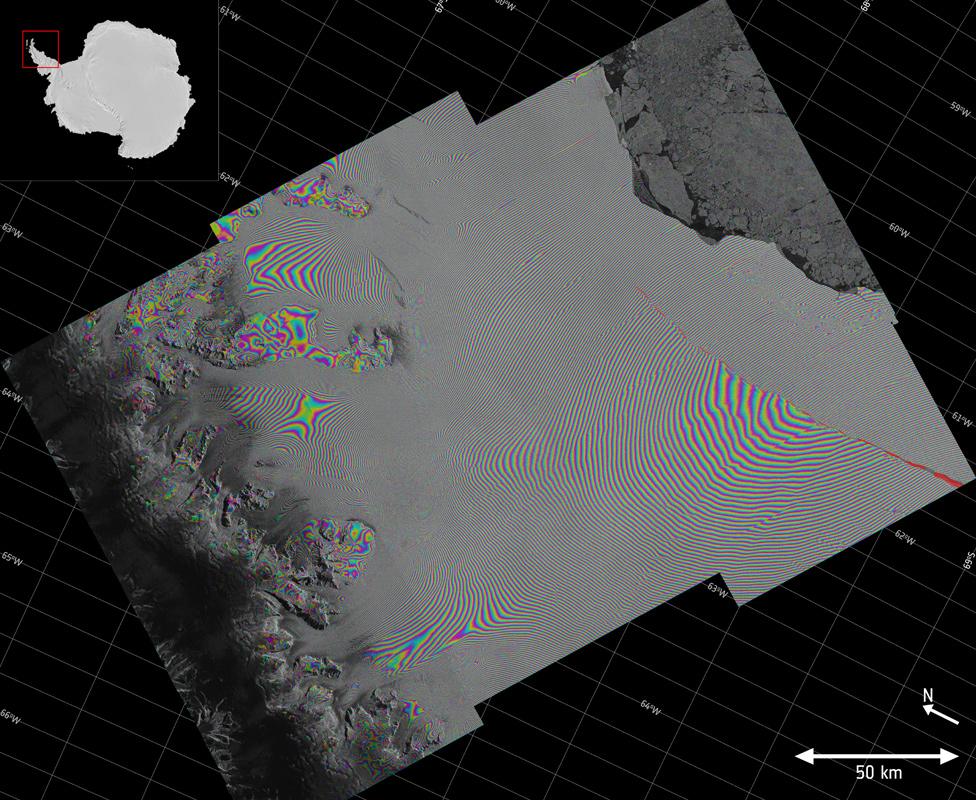

Prof Luckman is monitoring the crack’s position with the European Union's Sentinel-1 satellites. Their radar sensors report on the developing berg every six days, and can see the ice surface even through cloud and during the long polar winter nights.

Radar satellites are very effective at picking out the detail of the Larsen C crack

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external