Cassini ran through the 'big empty'

- Published

A raw image taken by Cassini as it turned to make Tuesday's second gap plunge

The American space agency says the Cassini satellite encountered very few particles as it dived between Saturn and its rings last week.

There were fears that the probe might hit fragments of ice or rock, and that these could cause significant damage.

Cassini made the plunge with its radio dish pointing forward like a shield.

But the latest analysis indicates there were hardly any impacts and those particles the probe did strike were only smoke-sized.

"The region between the rings and Saturn is 'the big empty,' apparently," commented Cassini project manager, Earl Maize, of Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

"Cassini will stay the course, while the scientists work on the mystery of why the dust level is much lower than expected."

The outcome is good news because four of the remaining gap-runs that Cassini will execute before terminating its mission in September will edge even closer to Saturn’s inner D-ring.

These manoeuvres also are expected to see the probe lead with its antenna in the shield configuration.

But last Wednesday’s experience means controllers can now approach these events with increased confidence.

Cassini is booked to make a further 21 plunges through the 3,000km-wide opening between the planet's cloudtops and the D-ring, with the next occurring at 19:38 GMT On Tuesday.

The dives are designed to return data of unprecedented resolution on the structure and dynamics of Saturn’s interior.

They should also allow the probe to weigh the rings, which will give scientists their best estimate yet for the age of these spectacular bands.

Currently, no-one is quite sure whether the rings are as old as the planet or are a relatively recent phenomenon, the result perhaps of a break-up of a moon or even a comet that got too close to the giant world.

Nasa intends to dump Cassini in the atmosphere of Saturn on 15 September.

After 20 years in space, the satellite is running low on fuel and controllers want to be sure there is no possibility of a future collision with the moons of Titan and Enceladus, which could conceivably support simple microbial life.

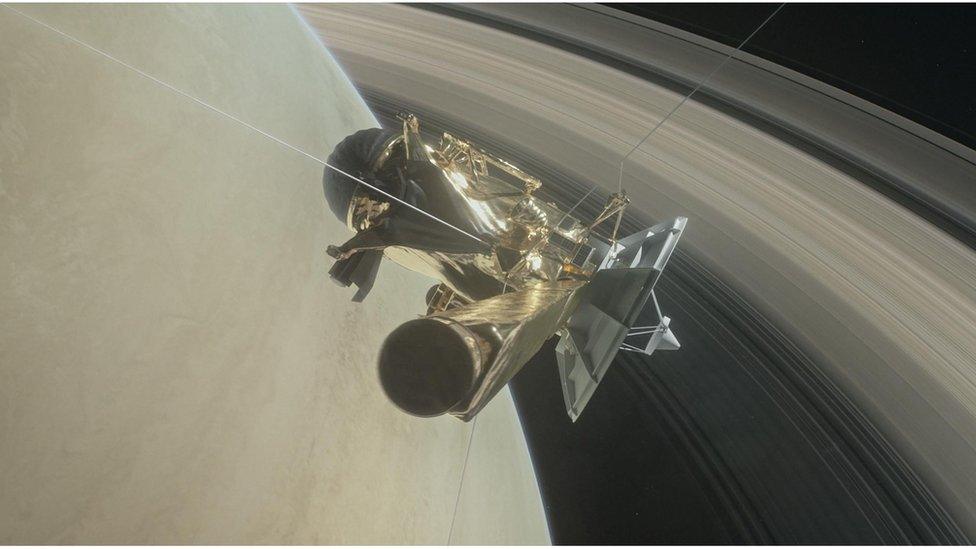

Artwork: Cassini will run the gap between the planet and the rings on 22 occasions

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published27 April 2017