Cassini radio signal from Saturn picked up after dive

- Published

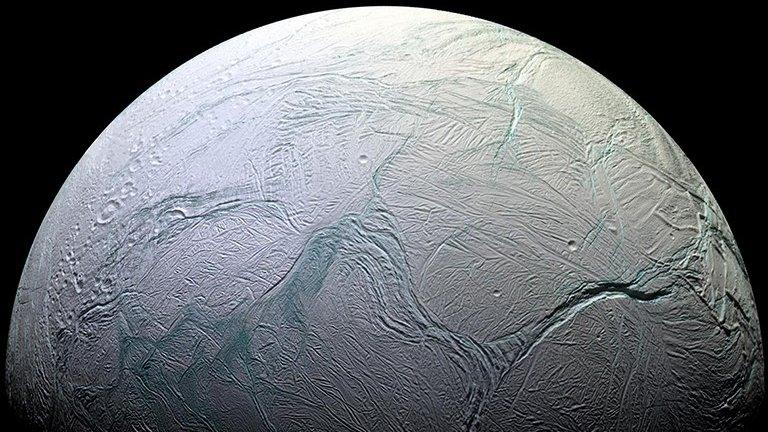

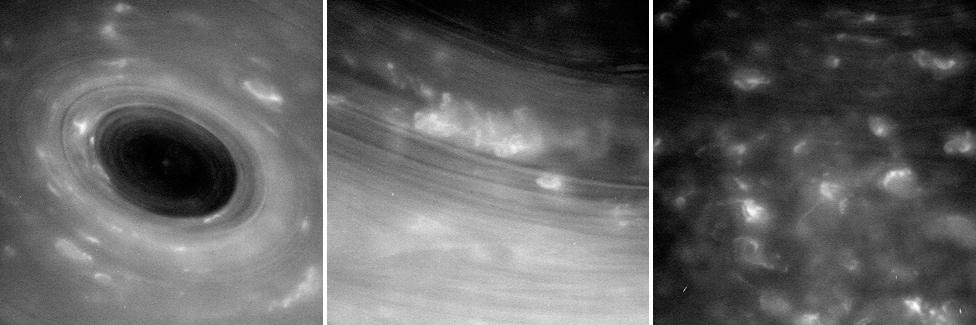

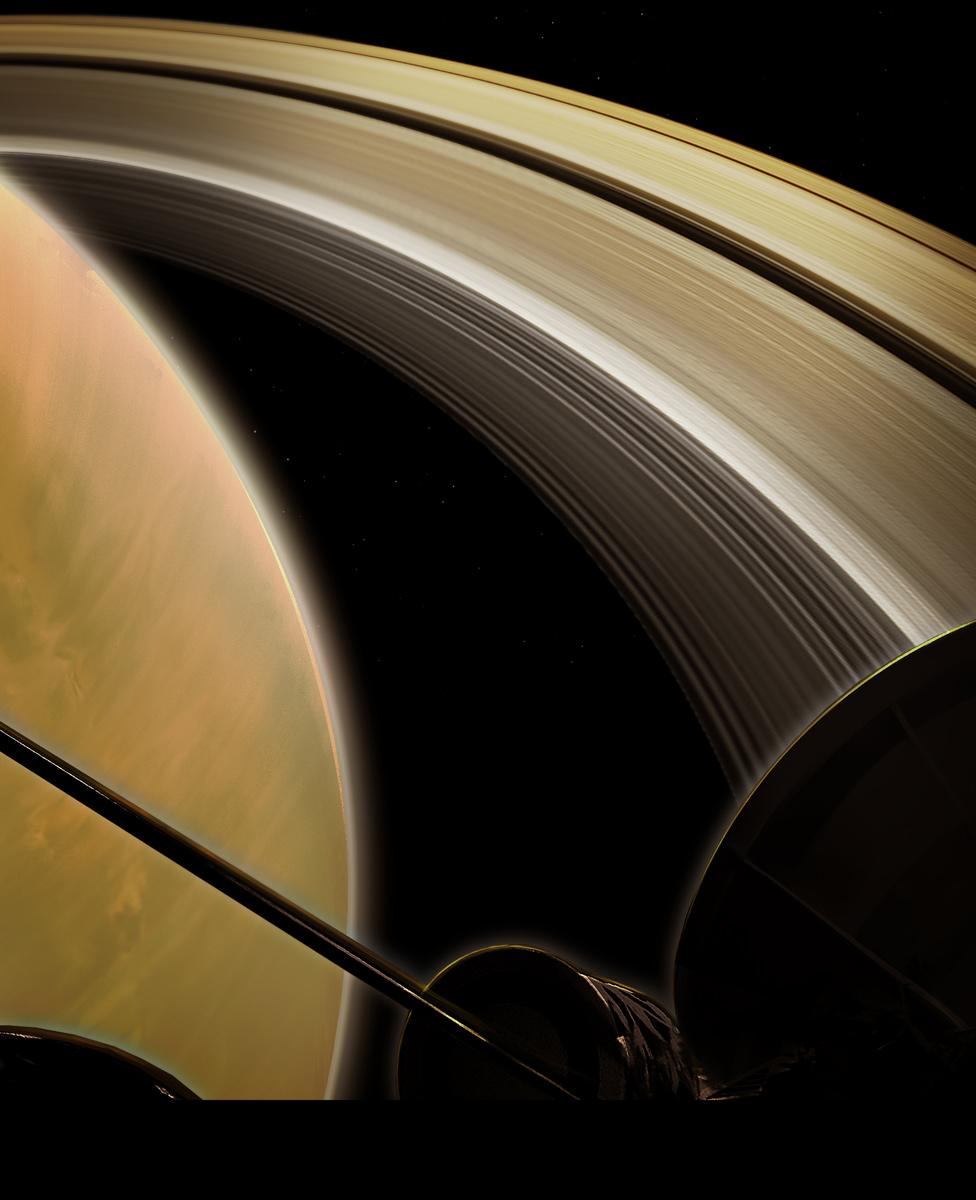

Raw images: The first gap-run pictures of the atmosphere. They will need full processing

The Cassini spacecraft is sending data back to Earth after diving in between Saturn's rings and cloudtops.

The probe executed the daredevil manoeuvre on Wednesday - the first of 22 plunges planned over the next five months - while out of radio contact.

Nasa's 70m-wide Deep Space Network (DSN) antenna at Goldstone, California, managed to re-establish communications at 06:56 GMT (07:56 BST) on Thursday.

The close-in dives are designed to gather ultra high-quality data.

At their best resolution, pictures of the rings should be able to pick out features as small as 150m across.

The Cassini imaging team has already started to post some raw, unprocessed shots on its website, external.

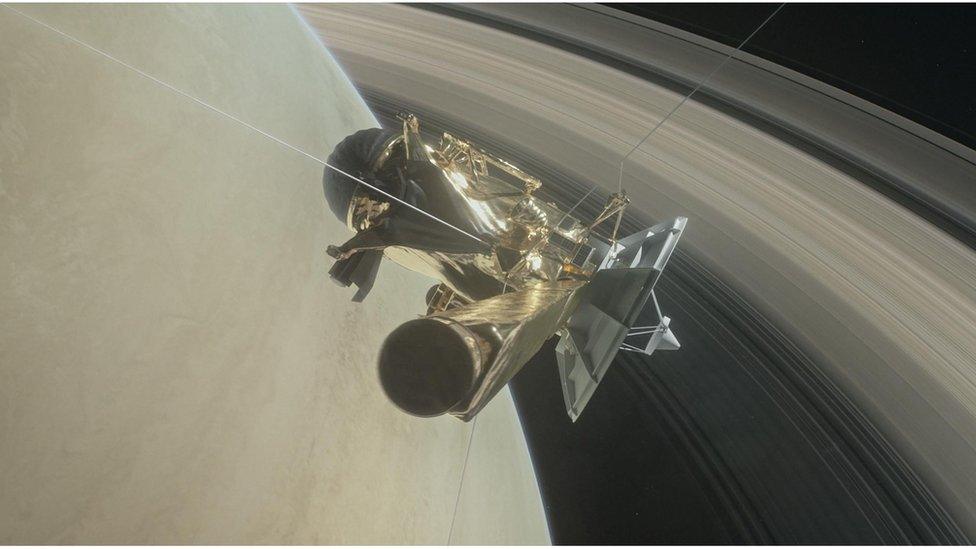

Artwork: Cassini will run the gap between the planet and the rings on 22 occasions

The gap-runs carry some risk, in part because of the velocity at which Cassini is moving - at over 110,000km/h (70,000mph). At that speed, an impact with even a tiny ice or rock particle could do a lot of damage, and so the probe is commanded to point its big radio dish in the forward direction, to act as a shield.

But that, of course, means it cannot also then talk to Earth at the same time.

"No spacecraft has ever been this close to Saturn before," explained Dr Earl Maize, Nasa's Cassini programme manager.

"We could only rely on predictions, based on our experience with Saturn's other rings, of what we thought this gap between the rings and Saturn would be like. I am delighted to report that Cassini shot through the gap just as we planned and has come out the other side in excellent shape."

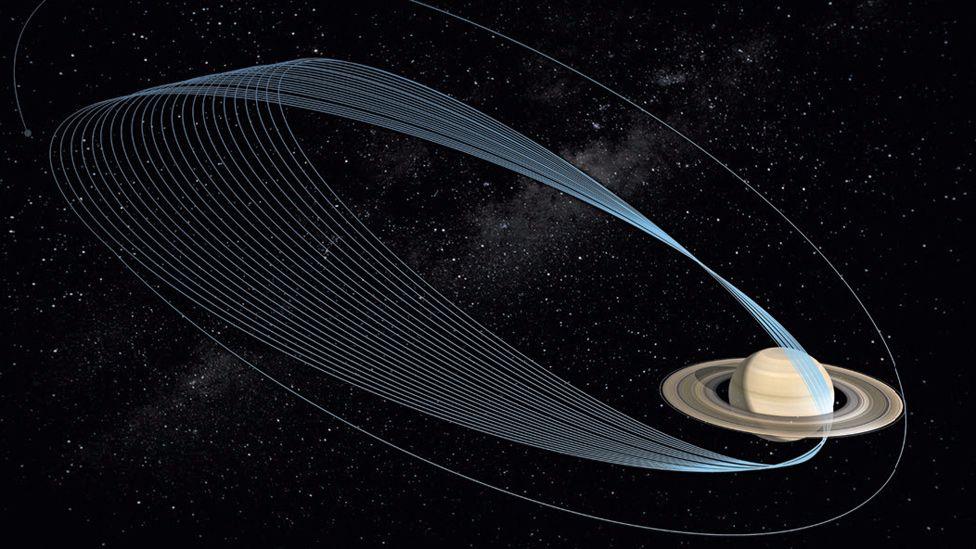

Another 21 similar dives (the next is on Tuesday) will now be made before the probe dumps itself in the atmosphere of Saturn. With so little fuel left in its tanks, Cassini cannot continue its mission for much longer.

The final orbits are designed so that Cassini comes in over the north pole

The US space agency (Nasa) is calling the gap-runs the "grand finale", in part because of their ambition. They promise pictures of unparalleled resolution and science data that finally unlocks key puzzles about the make-up and history of this huge world.

"We're going to top off this mission with a lot of new measurements - some amazing new data," said Athena Coustenis from the Paris Observatory in Meudon, France.

"We're expecting to get the composition, structure and dynamics of the atmosphere, and fantastic information about the rings," she told the BBC.

A key objective is to determine the mass and therefore the age of the rings. The more massive they are, the older they are likely to be - perhaps as old as Saturn itself.

Scientists will do this by studying how the velocity of the probe is altered as it flies through the gravity field generated by the planet and the great encircling bands of ice.

Luciano Iess: "We'll get to understand the interior structure of the giant planet"

"In the past, we were not able to determine the mass of the rings because Cassini was flying outside them," explained Luciano Iess of the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy.

"Essentially, the contribution of the rings to the gravity field was mixed up with the oblateness of Saturn. It was impossible. But by flying between the rings and the planet, Cassini will be able to disentangle the two effects.

"We're able to tell the velocity of Cassini to an accuracy of a few microns per second. This is indeed fantastic when you think Cassini is more than one billion kilometres away from the Earth."

Having the mass number might not straightforwardly resolve the age issue, however, cautioned Nicolas Altobelli, who is project scientist for Nasa's Cassini mission partner, the European Space Agency.

"We still need to understand the rings' composition. They are made of very nearly pure water-ice. If they're very old, formed at the same time as Saturn, how come they still look so fresh when they're constantly bombarded with meteorite material?" he pondered.

One possibility is that the rings are actually very young, perhaps the remains of a giant comet that got too close to Saturn and broke apart into innumerable fragments.

Coustenis, Iess and Altobelli discussed the end phases of the Cassini mission here in Vienna at the General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union.

Artwork: Some of the best science of the mission could come out these final orbits

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published22 April 2017

- Published13 April 2017