Antarctic iceberg crack develops fork

- Published

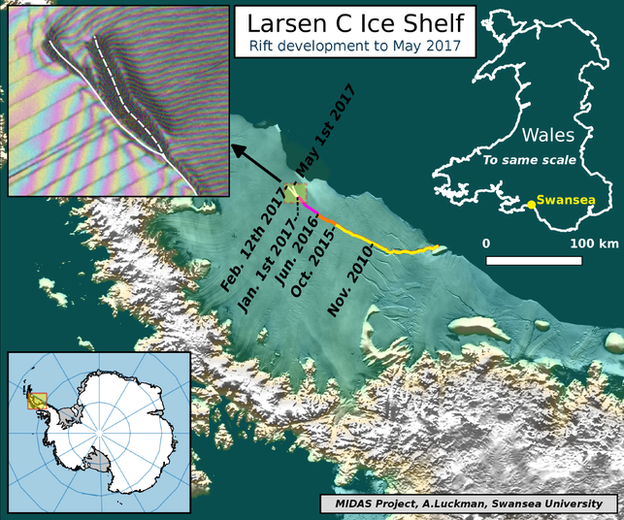

The crack in the Larsen C Ice Shelf that looks set to spawn a giant berg has suddenly forked.

Satellite imagery of the 180km-long fissure acquired in recent days shows a clear branching behaviour at its tip.

Quite what this means for the future evolution of the crack and the putative 5,000-sq-km berg remains to be seen.

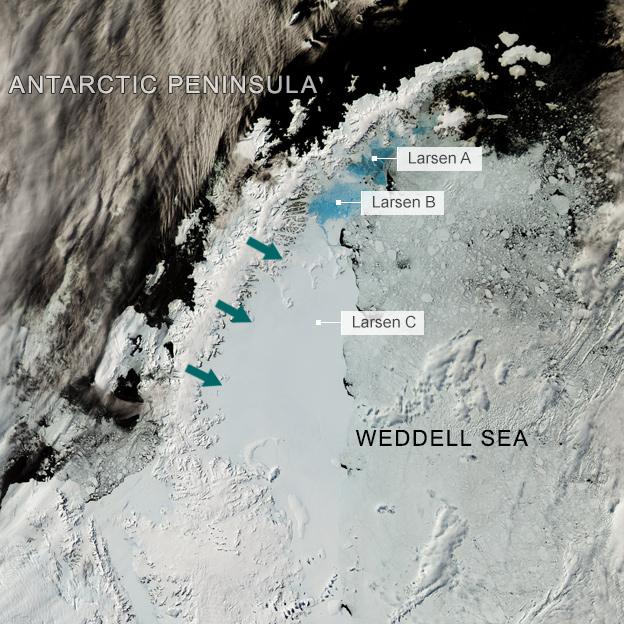

Larsen C is a floating projection of ice pushing east from the Antarctic Peninsula. It covers an area of the Weddell Sea the size of Wales.

The berg, when it calves, will remove about a quarter of the total shelf extent and could leave the remaining structure in a less stable configuration.

Scientists are concerned that Larsen C may be developing in a similar way to its siblings, Larsen A and Larsen B, which eventually collapsed at the turn of the century following their own big calving events.

The 10km-long fork does not increase the length of the rift; it merely gives it a two-pronged tip. The new branch has opened on the seaward side of the main crack.

The new feature was picked up in observations from the European Union's Sentinel-1 satellites that were downlinked on Monday. It was not there in data acquired six days earlier.

"This is one of the things I find so fascinating," said Prof Adrian Luckman from Swansea University, UK. "You look at these rifts and think they're moving really quite slowly. But when they go, they must go very quickly. People have said they could travel at anything up to the speed of sound. It would be amazing to be on the shelf to hear it," he told BBC News.

This is the most significant change in the rift since February.

Having ripped more than 60km through the shelf over the previous year, the crack then entered a so-called suture zone, which contains mostly softer, wetter ice.

This has slowed the progress of the rift tip.

That said, the crack's width continues to grow at about a metre a day and spans now more than 450m at the point where it is regularly measured.

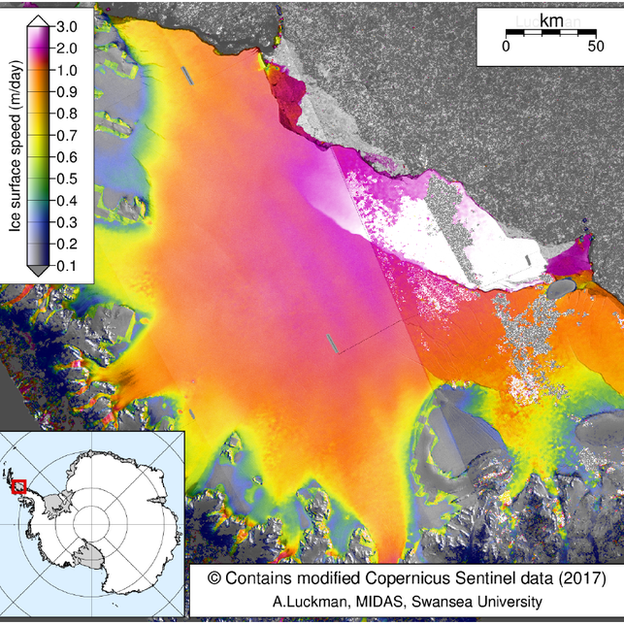

Prof Luckman explained: "I think what all this means is that the gradual and persistent opening of the rift has put a lot of strain on to this ice.

"But because the rift tip was in this area of basically softer ice that is very difficult to fracture, then the stresses have been transferred elsewhere and something has given, i.e. it has fractured in some of the ice that is more vulnerable to breaking which happens to be about 10km further back than the current rift tip."

And he added: "I'm not really surprised it's headed towards the shelf front because that's what the stresses suggested it would do."

Sentinel-1 continues to watch the crack. The length of the polar night is getting so long now as the Antarctic moves into winter that most optical satellites have given up gathering data.

Only spacecraft with radar instruments, like Sentinel-1, can hope to see the ice surface in darkness.

The British Antarctic Survey last week released a study which showed that a particular type of warm (foehn) wind that drops over the Peninsula mountains on to the Larsen C Ice Shelf is more frequent than previously realised, and could enhance melting.

Were Larsen C to collapse (and even if it did, this would still likely be many years from now), it would continue a trend across the Antarctic Peninsula.

In recent decades, a dozen major ice shelves have disintegrated, significantly retreated or lost substantial volume - including Prince Gustav Channel, Larsen Inlet, Larsen A, Larsen B, Wordie, Muller, Jones Channel, and Wilkins.

Prof Luckman's MIDAS Project is posting updates on the Larsen crack on its blog, external, and on its Twitter feed, external.

The warming effect of the foehn winds (green arrows) is felt at least 130km across the ice shelf

Melt ponds on Larsen C recently photographed from a British Antarctic Survey plane

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published30 April 2017