How to eavesdrop on urban bats with smart sensors

- Published

Brown long-eared bat - This bat's huge ears provide exceptionally sensitive hearing

Scientists are studying the urban life of bats in unprecedented detail using sensors installed in a London park.

The detectors eavesdrop on the nocturnal chatter of bats, picking up their ultrasonic calls and monitoring bat activity in real-time.

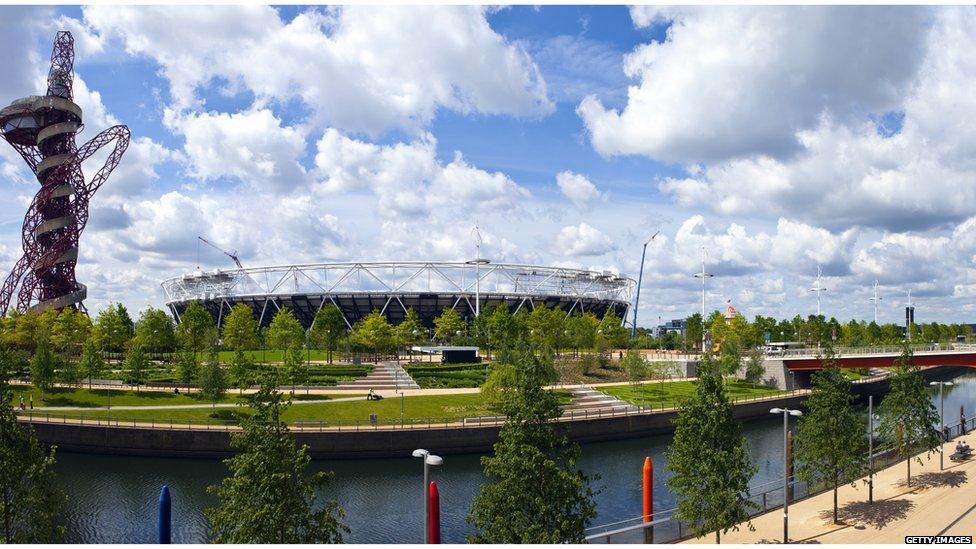

The project, external aims to investigate the health of bat populations at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London.

The smart devices have the potential to monitor the diversity of all sorts of wildlife, from birds to frogs.

Kate Jones, professor of ecology and biodiversity at University College London, is one of the world's leading experts in bat conservation.

"We've created this 'Shazam' for bat activity - bat calls - so we have put sensors into the park, which are connected up to the Wi-Fi and power," she explained.

"And we've put an intelligent device into the sensors so that they can pick up ultrasonic bat calls and then tell us if it's a bat and what species it is in real time."

Living lab

In what the researchers describe as a living lab, or Internet of Wild Things, smart bat sensors have been installed at 15 sites across the park. The monitors are automatically tracking the species present and their activity levels in real-time.

Brandt's bat

"Every time a bat's call is detected by one of the boxes, the machine learning algorithms first of all look to see whether it is a bat and if they think it is then another process then looks to see what species of bat that might be," said Dr Sarah Gallacher from Intel Labs Europe.

"And all this information is then passed out through the network to the cloud. We are deploying it and testing it in the real world in the wild, so we are calibrating and trying to understand how this technology and network works while it's in a very public space."

The technology is based on a deep neural network that runs on a chip. Dr Gabriel Brostow leads the team of computer scientists at UCL who worked on the platform.

"We teach this function to do the right mapping by giving it lots of examples," he said.

"So, in this case we had lots of audio files that were labelled by volunteers and bat experts who were able to tell us when a bit of an audio file corresponded to a bat call.

"And so we took those examples and we fed them into these machine learning systems - in this case neural networks - which were then tuned and adjusted so that eventually the system could do that kind of mapping automatically."

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London

The project aims to find out more about the diversity of bats in the park, from the UK's smallest bat, the common pipistrelle, to the largest bat, the noctule. In the future, the technology could be adapted to monitor other wildlife in the park - such as birds.

"Our vision is that we could start using these smart devices in the wild," said Prof Jones.

"So, smart sensors, Internet of Things, is very common in your house to monitor temperature and your heating schedule but what we've done here is a smart sensor in the wild.

"I think that our platform can start to monitor in a much more fine-scale way the biodiversity on our planet. "

The trial runs in the park until the end of the year. Eventually, all the data will be released - not only on bat biodiversity but on the science behind the experiment. So, in theory, you could even build your own bat detector for your garden.

Find out more about the project: Nature-Smart Cities – Sensing Nature in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, external.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published14 April 2016